Britain is facing a “retirement cliff” in engineering

- Published

- comments

Not enough young people are going into engineering

The great skills gap debate rages on. Engineering, the mainstay of some of our most important industries, is not loved or taken up by enough young people.

The average age of an engineer in Britain is 54. Only 6% of students in the UK are studying engineering or technology. Those are two uncomfortable statistics.

They were raised by Richard Daniel, the chief executive of Raytheon UK, the British arm of the American defence giant. Speaking at the International Festival for Business in Liverpool he said that the lack of skilled engineering students leaving Britain's universities "is of concern".

On the same panel was Marcus Bryson, the chief executive of GKN Aerospace, who said that Britain had the largest aerospace manufacturing sector outside the US - a great success story.

Britain enjoys 17% market share of global aerospace output and the sector employs 200,000 people. The world is at present in a super-cycle of aerospace construction with aviation giants Boeing and Airbus forecasting between 28,000 and 34,000 aircraft deliveries over the next 20 years. Demand is significant and growing - Britain needs people to fill those roles.

Business embassy

The International Festival for Business is a major pat on the back for Liverpool. Over 50 days, hundreds of businesses, large and small, will come to the city to discuss trade and exports.

Monday saw the launch of the festival itself and the British Business Embassy, a similar idea to the embassy launched to great acclaim at the Olympics. International delegations from India and the Middle East, to name just two, will forge links with British businesses.

As well as engineering, and fears about skills, the discussions ranged widely. How does Britain create real commercial value from the invention of graphene at Manchester University?

How does Britain move from a nation too reliant on financial services to one more balanced both by sector and - given this event is happening in north-west England - by geography.

Sir Terry Leahy, the former chief executive of Tesco who spoke today, said that when he was growing up in Liverpool in the 1970s all the talk was of decline.

That has now changed.

But it is skills that are at the heart of much of this. Just as Sir James Dyson and Lord Bamford, the chairman of JCB, have argued before, the British education system appears to struggle to enthuse young people about technically-based degrees. Women, in particular, are woefully under-represented.

Immigration debate

Lord Livingston, the trade secretary and former chief executive of BT, said that there was an obvious signal about the differing weight the education system gives to degrees as opposed to, for example, apprenticeships.

Students going to university to do a degree make up part of the school's league table results. Apprenticeships do not.

If the country is not creating the right skills then it will have to import them.

Sir Terry, speaking to me against the backdrop of a five feet tall model of an Airbus A380, said that the difficult immigration debate should not muddy the waters about how to support economic growth.

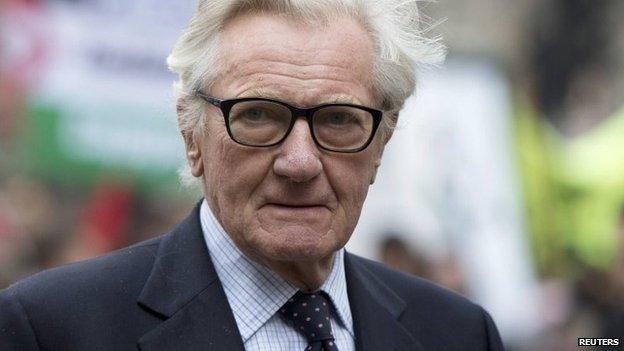

Lord Heseltine, economic advisor to 10 Downing Street, spoke at the event

"I think there is a concern that the immigration debate can get too loud," he said.

"Britain has always been open, it's a great strength. It's always been a place to visit, to do business, to learn - that must continue. Like everything else, in terms of public policy, immigration needs to be managed - and perhaps it could be managed better going forward.

"But we must always project an image around the world of being open."

The business people at this event in Liverpool, and that certainly does not mean it is reflected across the country, certainly appear keen to stay in the European Union.

"Business people want it," Sir Terry said. Lord Heseltine, now an economic advisor to Number 10 as well as still closely involved in the Haymarket Group publisher he founded, went as far as to declare UKIP "over" following their Newark defeat.

The murmur of disbelief that washed through the hall as he said it suggested that many in the audience were not convinced.

Victorian ambition

David Cameron did a short turn - claiming that Britain "was back". He agreed that Europe needed to reform and that the people who ran the EU needed to "understand the need for change".

It was a relatively oblique message to the European Commission and Jean-Claude Juncker, the chain-smoking former prime minister of Luxembourg, who is the leading candidate to become the next head of the EC.

That Mr Cameron's next stop after the festival was Sweden and a vital meeting with Angela Merkel will not have been lost on anyone.

The International Festival for Business is centred on the ornate St George's Hall in Liverpool, built in 1841 as a statement to Liverpool's ambition to be one of the most significant trading ports in the world.

The architecture historian Nikolaus Pevsner described the hall as one of the most important neo-classical buildings in the country.

Victorian Liverpool said it stood for "art, science, fortitude and justice". Given the grinding poverty of the time such lofty ideals were not always fulfilled.

Now the city is trying to rediscover its past. It just needs the skills to do it.