Can giving away trade secrets benefit business?

- Published

Tesla boss Elon Musk: "It is possible to create a compelling electric car"

Imagine you've spent the past few years and a very large sum of money developing new technology which you believe will be a game-changer in your industry.

Do you protect your investment carefully, and make sure your designs are protected by watertight patents - or do you allow your rivals to benefit from your research to boost the market as a whole?

Over the past couple of weeks, Elon Musk, the maverick boss of Tesla Motors, has been dropping some pretty strong hints that he is considering the second option.

The company has created the Model S, an electric car capable of accelerating as fast as a premium sports car such as the Porsche 911, while offering a range of 250 miles between charges. It is widely seen as being ahead of the game in the electric car market.

At Tesla's annual general meeting, Mr Musk said he was surprised that other carmakers had yet to come up with anything similar, and added that he was contemplating doing something "kind of controversial" with patents, in order to boost the electric car industry.

In an interview last week, I asked Mr Musk if that meant he was preparing to give technology away. His response was that I was "on the right lines".

He told me that there was nothing to be gained from creating technical barriers to the development of electric cars - or as he put it: "We don't want to cut a path through the jungle and then lay a bunch of landmines behind us."

Industry differences

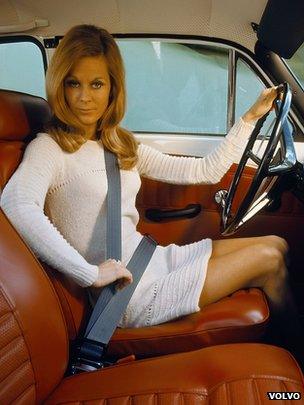

Volvo invented the three-point seat belt in 1959 before giving the patent away

If Tesla were to take such a step, it would break new ground in the motor industry.

Carmakers do share some patents, often within joint ventures when they have shared research costs. They frequently license designs to parts manufacturers, usually for a substantial fee. But as a rule, they don't give their ideas away.

The big exception to this rule was Volvo's decision in the early 1960s to give its design for a three-point seatbelt to other manufacturers. But that was a decision taken purely on altruistic grounds, and with no commercial benefit.

In some industries, however, technology sharing is relatively common. In IT, for example, the concept of "open source" is well-established. Both software and designs for hardware can be made available under a free licence, allowing people to use, distribute and modify them at will.

The idea is that this promotes collaboration between researchers, promotes faster development, and levels the playing field between small operators and big businesses. It can also lay the foundations for building new markets.

'Free researchers'

The Google-led Android initiative, for example, has created a software platform that anyone can use. As a result, there is now a thriving industry in developing apps for Android devices - not to mention the devices themselves.

One fan of this system is Adrian Bowyer. He founded the RepRap Project - an initiative begun in 2005 which made designs for 3D printers freely available online. He also runs RepRapPro, a company which sells complete 3D printer kits. He says the open source model has been hugely beneficial.

RepRap shared designs for its 3D printers online

"It turns all our customers into developers," he says. "Everybody who buys one of our machines can find out how it works, edit the programmes that control it, and often they send us suggestions for improvements. We have an enormous number of free researchers available."

The obvious risk is that rivals simply take advantage of the chance to get hold of some free research, but Mr Bowyer says that does not usually happen.

"By and large they don't," he says. "They do take some, but by then we've probably moved on anyway, because it's a fast moving field."

Mobile wars

Yet pitfalls do exist, according to Alex Wilson, a patent lawyer at Powell Gilbert. He says the mobile phone industry offers some examples of both the benefits and the downsides of sharing technology.

In the 1980s, European telecoms firms worked together to create a common platform for mobile phones, pooling their patents to create what ultimately became the global standard, GSM.

"It was extremely successful at driving the technology and getting it adopted around the world," says Mr Wilson.

"The problem arose later when it was so successful that all the players involved in the market began fighting over just how much they should pay for the use of those patents."

Apple and Samsung benefited from the common standard created by others but are now protective of their own patents, says Mr Wilson

He thinks the creation of a common standard also allowed late arrivals into the phones market, such as Samsung and Apple, to steal a march on their more established rivals.

"If you look at what has happened to European manufacturers such as Nokia and Ericsson, they have been left behind by larger players who have run with their technology," he says.

Now, Apple and Samsung are the dominant players - and both have become extremely protective of the patents they have developed themselves.

Tesla - game changer?

So what of Tesla? A great deal hinges on exactly what technology the company decides to give away. It has already indicated that it will help other manufacturers to adapt their cars to use its network of "supercharger" fast-charging stations.

That would make sense, since a lack of charging infrastructure is widely believed to be a factor holding back sales of electric vehicles.

But if it were to offer up the secrets of the Model S, would that be a game-changer for the industry?

"That depends how big an advantage they actually have over other manufacturers," says Jay Nagley of automotive consultants Red Spy.

"With the Model S, they seem to have done an impressive job developing existing technology, but they don't seem to have anything that's actually new technology.

"They're market leaders, but they seem to be on the same lap as the rest of the field."

- Published6 June 2014