De La Rue: Licensed to print money

- Published

-montage-daylight.jpg)

De La Rue is the world's largest commercial banknote printer

There are few companies in the country more concerned about their security than De La Rue. This, after all, is a firm with a licence to print money.

In fact, it has lots of licences to print a dizzying array of money, from dozens of countries around the world.

Behind the walls of an unspectacular, but well-guarded building, stand machines that keep many of the world's economies ticking over, working 24 hours a day to print notes.

If you've ever wondered where the money tree grows, then worry no more - I've found it - although it's a factory rather than a tree and powered by machines and high-cost ink, rather than magic.

It is little wonder De La Rue takes security seriously, gently asking you to hand over your wallet before you walk into the factory - checking your passport and inspecting your bags.

"Security is of paramount importance to the company, from how we treat visitors to how we make the notes," says chief operating officer Colin Child.

Visitors are normally customers or industry professionals, because very few people get to look round this factory.

The BBC team were the first people ever to broadcast from the site. And we aren't allowed to say where we were.

'We've invested very heavily'

But at a time when the need to export has become a pressing debate among politicians and economists, De La Rue offers an interesting example.

Steph McGovern reports from banknote maker De La Rue

While it does print banknotes for the Bank of England, almost all of its business is for export: other nations' currencies form the huge majority of its order book.

This morning, for instance, it is the Kuwaiti dinar that is keeping the staff busy.

As I talk to Mr Child, we stand next to a pile of maybe 2,500 large sheets of paper, each embossed with 45 perfect banknotes. This unassuming pile is worth about £2.5m ($4.2m).

"We've invested very heavily across our group over the past three years," he says.

"The level of sophistication in the notes is growing every year. All parts of the market are growing, all around the world.

"When debit and credit cards were introduced into the UK, they said we'd be finished. But here we are, still going stronger than ever.

"Demand for banknote currencies is growing all the time."

But are we getting bored of notes? What about the growth of internet banking, contactless payments, PayPal and their ilk?

Well, if demand is waning, it's not showing. There is one statistic that tells the whole story: if you stacked the banknotes produced every week by De La Rue, they would reach the top of Everest, twice.

Yet as prolific as the company is at making notes, there will always be those who are just as determined to copy them.

The history of counterfeiting is as old as the history of money, and the battle becomes ever more sophisticated.

Despite other forms of payment, demand for traditional banknotes is high

'Covert measures'

The banknotes coming out of this factory have an array of security measures built into them, from the familiar array of watermarks and complicated etchings, through to see-through images and markings that only show up under ultraviolet light.

But then there is a third wave, known as "covert measures", that are often known only to a nation's central bank.

"The trick is to make a note that is sophisticated enough that it's almost impossible for someone else to copy one of them successfully, but where we can make millions of them with great precision," says the company's head of planning and logistics, Andrew Davidson.

"The battle against counterfeiters goes on constantly." Behind him, the new notes are being scrutinised minutely to ensure each is perfect.

They are also, in many cases, rather lovely to look at.

British banknotes have always been solid and respectful, but the world is full of notes emblazoned with birds, animals, bright colours and rather daring designs.

-heron-detail-high-res.jpg)

Polymer banknotes are more expensive, but last longer

Polymer banknotes

Step forward Alan Newman, De La Rue's director of design and 10 times winner of the Banknote of the Year.

For the past three years, he has won the title for Kazakh notes, all of them colourful and clear.

My favourite is his award-winning Samoan 20-tala note, a cheerful yellow note with a waterfall on one side and a rather chubby bird, called a manumea, on the other.

He tells me: "It can take anything from six months to two years to get a note into circulation."

The industry is changing, of course.

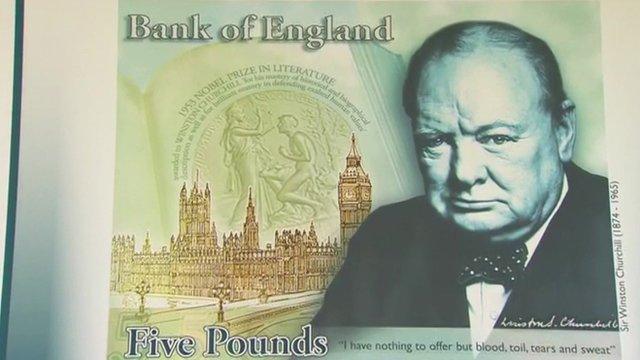

Polymer banknotes are soon to be adopted by the Bank of England, as they have been by some other countries, although it's still not decided who will print them.

This sort of banknote, says Mr Child, is a "small, but growing" part of the industry. They are more durable but cost more to make.

Around us, the hum of the presses rumbles on. They are huge machines, continually printing money that goes round the world - the secret factory with the global impact.

- Published26 April 2013

- Published8 October 2013