Should we fear the robots of the future?

- Published

Does science fiction correctly predict the future?

The world's oldest technology magazine is the MIT Technology Review.

Published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in 2011 it produced a special supplement of original science fiction stories written by top writers from the genre.

The Review says its normal mission is to identify important new technologies, and decipher the practical impact they will have on our lives.

The sci-fi edition - with contributors such as Cory Doctorow and Elizabeth Bear - was an attempt to do that in an unusual way. The magazine called this "hard" sci-fi.

There's a great tradition at work here. When the MIT graduate John Campbell took over the editorship of Astounding Stories Magazine in 1937, he changed the name to Astounding Science Fiction, and insisted that the fiction contained convincing science and characters.

This ushered in what people say was the golden age of sci-fi writing, producing a hugely influential magazine.

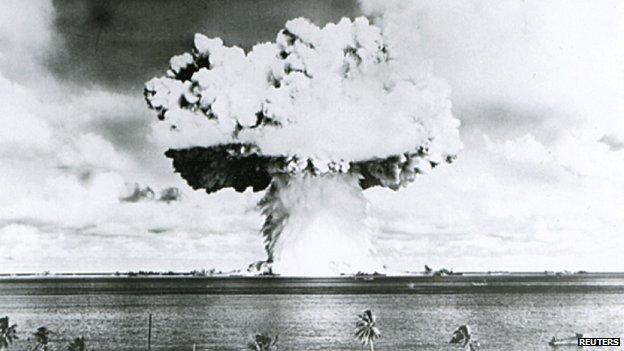

One Astounding story told how to make the atomic bomb one year before Hiroshima.

But trying to predict the future is hard, and often wrong; that does not (however) mean it's a futile exercise. If, that is, prediction is what sci-fi is about.

There are different critical views about this. Some people argue that far from being far-seeing, most science fiction simply projects current concerns into a fantasy future unhindered by contemporary reality. But futurology it really isn't.

Possible futures?

The other month at the St Gallen Symposium debates in Switzerland, I had a chat about some of this with the Toronto-based sci-fi author Robert Sawyer.

He has written more than 20 acclaimed books, such as Flash Forward, The Terminal Experiment, Hominids, and Mindscan.

The Astounding Science Fiction described how to make a nuclear bomb

In 2003 Mr Sawyer won the top sci-fi honour, the Hugo award. His work is not about aliens and rocket ships. Instead he says it is more about social interactions with the future.

He thinks the job of sci-fi writers as a whole is to produce "a smorgasbord of plausible futures", not to predict which of them will actually happen.

Mr Sawyer points out how popular sci-fi has been in totalitarian societies such as the Soviet Union, as a way of writing about things that cannot openly be talked about.

He is the most popular foreign sci-fi writer in China, he says. Fictionalised into the near future, he can write about attempts to control the internet, for example, circumventing conventional here-and-now censorship.

Sci-fi author Arthur C Clark worked out the principles of orbiting satellites

We talked about Sir Arthur C Clarke, inventor of the communications satellite. In 1947, 10 years before the first space satellite was launched, Clarke worked out that a satellite 23,000 miles above the equator would stay stationary in the sky.

From this idea - published as a working paper in Wireless World - came what is now the global satellite network.

And then there is the chilly epic 2001 A Space Odyssey, jointly developed by Clarke and the director Stanley Kubrick.

The movie's famous computer Hal 9,000 was a wonderful forerunner of artificial intelligence: Hal could understand speech, beat humans at chess, recognise faces, and attempt moral reasoning.

"This is the continuing agenda of the computer revolution," says Mr Sawyer.

Too optimistic?

Robert Sawyer says his books are optimistic. Today is better that 50 years ago, in 50 years' time things will be better still.

They know this in China, he says, at least from the material experience of the past 30 years. But in the West, how many can say they are better off than a few years ago? We are stalled in the old paradigms, unable to see what is happening to the world.

Should we fear the robots of the future?

Is Robert Sawyer not guilty of techno optimism, I asked him: a sort of over confidence about what science can and will bring about, whatever it is?

No he says, it's humano-optimism. In the face of widespread resistance to the idea, you can change human nature, and it's happening, he says.

Mr Sawyer gives the example of the way men are now involved with bringing up children in the West in a way undreamed of 60 years ago. And the creation of the European Union after centuries of European strife.

"Sci-fi is just as much about social science as technology," he says.

Robert Sawyer is also enormously optimistic about something that worries many people: the future of energy. With his sci-fi writer's approach, he foresees a vast expansion of sustainable energy, bringing down the cost of energy to approaching zero.

Rapacious robots?

Meanwhile, some futurologists - notably the American Ray Kurzweil - are busy predicting that moment out in the 2050s when artificial intelligence might - they argue - at last outstrip its human counterpart, and then go on getting better.

It follows the computer power expansion laid down in 40 years ago in Moore's Law: a doubling of the power on a silicon chip every two years.

"When we have machines that are as intelligent - and then twice as intelligent as we are," says Mr Sawyer, "there is no reason why that relationship cannot be synergistic rather than antagonistic."

He adds that the single biggest flaw with people being fearful of future clever computers or robots "is the idea that a superfast, super powerful intelligence that is not human will share human rapaciousness".

Ideas such as this are explored in Robert Sawyer's sci-fi trilogy WWW - Wake, Watch and Wonder. They describe the world wide web gaining consciousness.

Fact or fiction? For the moment, I will leave you to decide.