Are Europe's banks being prosecuted - or persecuted?

- Published

Terrorism in Sudan in 2004: US sanctions on the country imposed in the 1990s were broken by BNP Paribas

Even BNP Paribas cannot shrug off a $9bn (£5.1bn) fine.

The bank is the fourth biggest by assets in the world and has been found guilty of violating US economic sanctions against Sudan, Iran and Cuba.

It had repeatedly protested that it did not violate any European law, but US prosecutors say that is beside the point.

BNP Paribas operates in the US through Bank of the West and First Hawaiian Bank, and is therefore bound by US law.

It is not the first to fall foul of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) that prohibits trading with sanctioned governments.

HSBC, Standard Chartered, ING, Barclays, Credit Suisse and Lloyds have all been hit with fines for violations since 2009.

It's not gone unnoticed that they are all European banks.

And the penalties are getting bigger.

Further inquiries

Now other European banks fear this latest fine shows American prosecutors are targeting them with increasing aggression.

Commerzbank of Germany, Credit Agricole and Societe Generale of France and Unicredit of Italy are all under investigation over suspected sanctions violations or money laundering.

Deutsche Bank faces investigations into the rigging of interest rates and foreign exchange manipulation.

Although it says it does not believe it has violated US laws, it is raising $11.6bn in extra capital, partly as a cushion against any future legal costs.

John Raymond, senior analyst of European banks at CreditSights Research, says: "The European banks are worried.

"You have to remember they are undergoing stress tests and the possibility that they might receive heavy fines means the tests may demand they have extra capital to meet those fines."

Mood change

However, the truth is the US authorities are still fining American banks far more than European ones.

A Financial Times study, external in March of 200 fines and restitutions since 2007, showed that of a total of $99.5bn in penalties, only $15.5bn came from foreign banks.

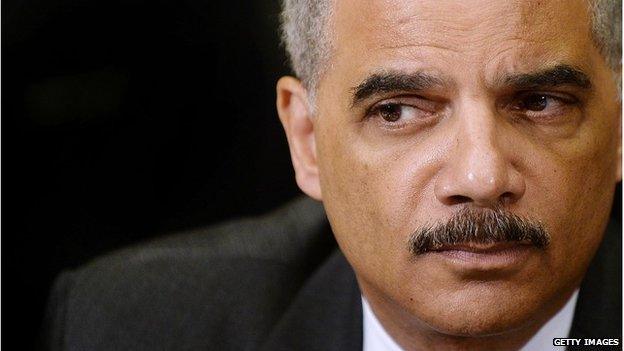

US Attorney General Eric Holder: "There is no such thing as too big to jail."

In fact there is a pattern to the prosecutions.

The European banks have hit the headlines with their sanction-breaking activities and tax evasion for which they have received fines.

The Americans have been have been forced to pay fines and compensation for issues over mortgage-backed securities and home loan fraud where victims have had to be compensated.

But both European and American banks have fallen victim to a change in mood among the US authorities.

Over the past few years many believed the Department of Justice (DoJ) had gone soft on big banks.

In March last year, US Attorney General Eric Holder seemed to confirm this to the Senate Judiciary Committee, external.

He said: "I am concerned that the size of some of these institutions becomes so large that it does become difficult for us to prosecute them when we are hit with indications... it will have a negative impact on the national economy, perhaps even the world economy."

French politicians were swift to exploit this, with the finance minister and the governor of the bank of France publicly stating that a massive fine would cripple BNP Paribas' lending ability and slow down lending worldwide.

But Mr Holder has been back on the offensive. Last month on the Department of Justice's website, external he insisted: "There is no such thing as too big to jail. To be clear: no individual or company, no matter how large or how profitable, is above the law."

Benjamin Lawsky - a force to be reckoned with as New York State's most senior financial regulator

And then there is Benjamin Lawsky.

He is the 44-year-old superintendent of New York State's Department of Financial Services (DFS).

The DFS cannot criminally charge a bank or individuals, but Mr Lawsky has been loud and influential in his demand for accountability from the banks.

It is thought the DFS's own investigation into Credit Suisse in March pressurised it into pleading guilty to aiding tax evasion and paying penalties of $2.6bn just two months later.

Back in 2012, he forced Standard Chartered to a settlement by the radical measure of threatening to withdraw its banking licence.

Known by Le Temps newspaper in France as "Le Bete-Noire des Grandes Banques", external he has been urging the resignation of senior executives at BNP Paribas.

In the face of this new assertiveness, the French bank has been caught on the back foot.

As the US authorities opened early negotiations, reportedly threatening a $16bn fine, the bank offered to pay a mere $1bn.

That may just be bargaining chutzpah, but the bank put aside just $1.1bn to cover legal costs. In April it admitted, external: "There is the possibility that the amount of the fines could be far in excess of the amount of the provision."

It had utterly failed to grasp the seriousness of the situation.

Paying the price

And the situation was serious, particularly the accusations of "stripping" - the deliberate removal of key details, to keep sanctioned transfers of money away from the prying eyes of regulators.

Investigators eventually found that even as late as 2011 while the bank was insisting that it was co-operating with the authorities, it was continuing to break rules on sanctions.

Again the bank appeared not to have taken the litigation threat seriously. It is now paying the price.

In sharp contrast JP Morgan Chase, facing some $20bn in penalties in the past year, has been steadily building up a war chest of more than $28bn to meet the legal pay-outs.

The New York Times recently described, external how chief executive Jamie Dimon personally negotiated with the Attorney General hours before the DoJ was due to announce civil charges. "A move," it reported, "that averted a lawsuit and ultimately resulted in the brokered deal."

And the American banks are still as much in the firing line as the Europeans.

The DoJ is demanding $10bn from Citigroup to settle investigations into its sale of worthless mortgage-backed securities. It is also negotiating a $13bn settlement with Bank of America.

There is much more to come, for instance the probes into interest rate and foreign exchange market manipulation. European and US authorities are both investigating a raft of banks, blind, it seems, to which side of the Atlantic they come from.

- Published3 June 2014

- Published20 May 2014

- Published20 January 2014

- Published11 December 2013