Food waste reduction could help feed world's starving

- Published

- comments

One third of all food produced is wasted, the UN estimates

"If food was as expensive as a Ferrari, we would polish it and look after it."

Instead, we waste staggering amounts.

So says Professor Per Pinstrup-Andersen, head of an independent panel of experts advising the UN's Food and Agricultural Organization on how to tackle the problem.

Some 40% of all the food produced in the United States is never eaten. In Europe, we throw away 100 million tonnes of food every year.

And yet there are one billion starving people in the world.

The FAO's best guess is that one third of all food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted before it is eaten.

Food waste

33%

of all food is wasted

$750bn

cost of waste food

-

28% of farmland grows food that will be thrown away

-

6-10% of greenhouse gases come from waste food

-

39% of household food waste is fruit and vegetables

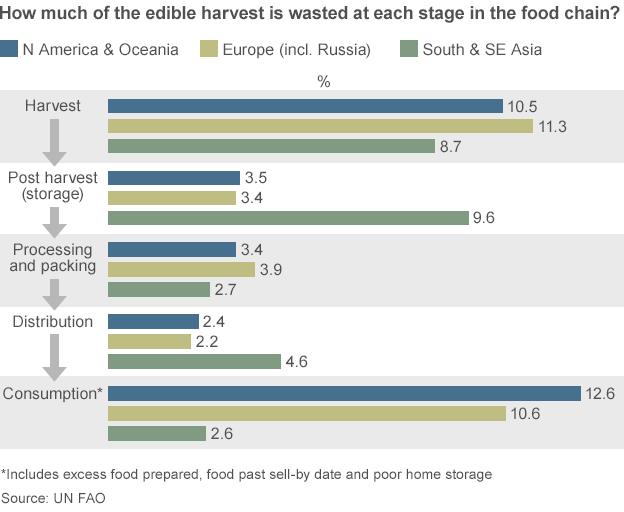

The latest report, external from the expert panel of the UN Committee on World Food Security concludes that food waste happens for many different reasons in different parts of the world and therefore the solutions have to be local.

Take Chris Pawelski, a fourth generation onion farmer from the US. Mr Pawelski has spent months growing onions in the rich, black soil of Orange County, New York, but the supermarkets he sells to will only accept onions of certain size and look.

Chris Pawelski works with a food charity to ensure all of his produce finds a home

"If it's too wet or too dry, the bulbs simply won't make the two-inch size that's required," he says.

"There might be imperfections and nicks. There's nothing wrong with that onion. It's fine to eat. But the consumer, according to the grocery store chain, doesn't want that sort of onion."

In the past, rejected onions would have been sent to rot in a landfill. Now Mr Pawelski works with a local food charity, City Harvest, to redistribute his edible but imperfect-looking onions.

City Harvest says in 2014 it will rescue 46 million pounds - about 21 million kilograms - of food from local farmers, restaurants, grocers and manufacturers for redistribution to urban food programmes.

Onions can be rejected by supermarkets because of their size as Michelle Fleury reports

In rich countries, supermarkets, consumers and the catering industry are responsible for most wasted food. But supermarkets have come under particular pressure to act.

UK supermarket chain Waitrose is attacking food waste in all parts of its business. The upmarket grocery chain cuts prices in order to sell goods that are close to their "sell by" date, donates leftovers to charity and sends other food waste to bio-plants for electricity generation. The idea is for Waitrose to earn "zero landfill" status.

But then there are consumers like Tara Sherbrooke. A busy, working mother of two young children, she works hard to avoid wasting food but still finds herself throwing some of it away.

Working mother Tara Sherbrooke explains why she finds it a "challenge" not to waste food

"I probably waste about £20 worth of food every week," she says. "It's usually half-eaten packets of food that have gone past their 'best before' date."

In the UK, studies have shown that households throw away about seven million tonnes of food a year, when more than half of it is perfectly good to eat.

Part of the problem is poor shopping habits, but the confusion many consumers have with "use by" and "best before" food labels is also a factor. "Use by" refers to food that becomes unsafe to eat after the date, while "best before" is less stringent and refers more to deteriorating quality.

Plus, as Prof Pinstrup-Andersen points out, food in wealthy countries takes up only a relatively small proportion of income and so people can afford to throw food away.

In developing countries, the problem is one not of wealth but of poverty.

In India's soaring temperatures fruit and vegetables do not stay fresh on the market stall for long. Delhi has Asia's largest produce market and it does have a cold storage facility.

In Delhi, keeping fruit fresh is a big problem for stall holders

But it is not big enough and rotting food is left out in piles. There is not enough investment in better farming techniques, transportation and storage. It means lost income for small farmers and higher prices for poor consumers.

In terms of calories, farmers harvest the equivalent of 4,600 calories of food per person per day. But on average only 2,000 of those calories are actually eaten every day - meaning more than half the calories we produce are lost on their way from farm to dinner fork.

There is enough food for everyone, just a lot of inefficiency, the FAO report concludes.

The environmental impact of all this wasted food is enormous. The amount of land needed to grow all the food wasted in the world each year would be the size of Mexico.

The water used to irrigate wasted crops would be enough for the daily needs of nine million people. And wasted production contributes 10% to the greenhouse gas emissions of developed countries.

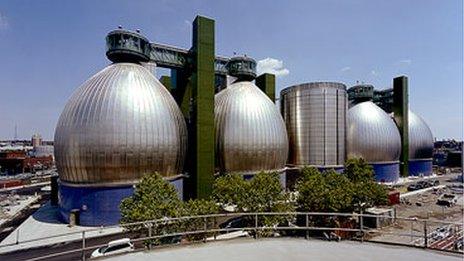

This plant in Brooklyn uses food scraps to produce energy

Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant in Brooklyn, New York, is one project trying to reverse that environmental damage. The plant takes food scraps from local schools and restaurants and converts them into energy. Inside towering, silver eggs food waste is mixed with sewage sludge to create usable gas.

The pilot programme is particularly timely. New York City's restaurants will be required to stop sending food waste to landfills in 2015 and will have to turn to operations like these as alternatives.

So progress is being made. Waste food is high on the agenda politically and environmentally.

But there is still much more work to be done. As Prof Pinstrup-Andersen admits: "We don't really know how much food is being wasted. We just know it's a lot."

- Published2 July 2014

- Published6 April 2014