From revolution to business empire

- Published

How an alarm empire grew out of the ashes of the Czech Velvet Revolution

There are times in life when the stars align to create the perfect business opportunity. For Dalibor Dedek, chief executive of Czech alarm and security company Jablotron, that moment came in January 1990.

The collapse of communism in Czechoslovakia brought with it mass privatisation of businesses, a rush to buy private property, and shops suddenly crammed with western consumer goods.

At precisely the same time, President Vaclav Havel emptied the country's prisons.

On New Year's Day 1990, he signed a general amnesty, and 30,000 convicted criminals were released overnight.

"It was like a signal from heaven," Mr Dedek tells the BBC at the company's headquarters in Jablonec nad Nisou, a mountain town near the Polish and German border, chiefly known for its cut-glass and costume jewellery.

"People had spent their life savings to buy small businesses and so on. And on the other hand, all the thieves had left prison. It was like suddenly removing all the cages in the zoo."

"The people who had property were very afraid, and the thieves found their prey everywhere, because there was no protection, no alarms; the level of security was very low," Mr Dedek explains.

Dalibor Dedek says he knows a lot of rich people who are "poor creatures"

Alarming start

An initial business venture - making industrial control systems for a large, state-owned company - almost ended in bankruptcy for Mr Dedek and his three friends.

"It was a nightmare. Me and my wife's parents had taken out mortgages on their houses to help us. I used to wake up in the middle of the night after dreaming I'd had to tell my mother-in-law she was homeless," he says.

Then they hit upon the idea of electronic security systems.

"There were many obstacles, because there was no existing market in this field.

"People were interesting in buying our alarms, but there was no-one qualified to install them. So our first priority was educating the installers," he says.

The vast majority of the company's products are now sold outside the Czech Republic

Exporting success

Jablotron has grown from four geeks soldering circuit boards in an attic to a global electronics business with annual sales of $100m (£58m).

The company employs some 450 people in the Czech Republic and more at a second factory in China.

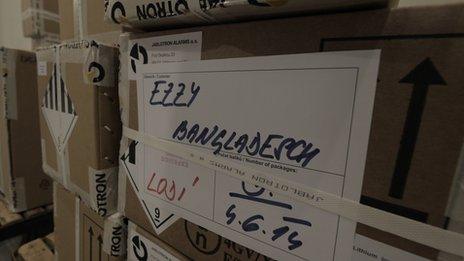

Some 85% of the company's products are exported; pallets in Jablotron's warehouse were labelled "Bangladesh", "Malaysia" and "Sweden".

However, the emphasis has remained on providing not just alarms but comprehensive security solutions.

The company operates the country's largest monitoring network, which receives signals from some 40,000 alarm systems across the Czech Republic.

Jablotron's products now extend beyond alarm systems

Upsetting the bank manager

Mr Dedek himself cuts a slight, stooping, rather scholarly figure, a man in his mid-fifties who moves at great speed through his company's spotless workshops and hi-tech assembly halls, pausing briefly to examine a piece of circuit board.

Jablotron has made him extremely rich. But he says that money has been poured back into the company. Certainly there are no ostentatious signs of wealth, no Porsche SUVs idling in the car park.

The atmosphere inside the company headquarters is diligent and professional, yet collegial and relaxed.

"I don't express richness in numbers. Someone is rich if they have a wealth of knowledge, if they can do something for others. I know a lot of people who have plenty of money who are very poor creatures," he told the BBC.

"I once made my bank manager very upset when I told him that I count money in the same way as water. It's very important for the industry to run, but it's just a medium. It's not an end in itself."

Beyond security

His side projects include building an 80-bed homeless shelter in Prague; when it opened he spent the night there to test the facilities.

A few years ago Jablotron created an outsized mobile phone that looked like a regular telephone.

When a prototype went on display at a Hong Kong technology fair, people initially thought it was a joke. But a chance TV report led to orders for 200,000 units within a week and there is now a whole division, Jablocom, making them.

Mr Dedek has largely withdrawn from the day-to-day running of the firm, leaving that to carefully handpicked colleagues who come to him for advice.

"I'm ageing, and the company's growing, and I do not want to be a bottleneck for the company. To be honest with you these days I feel more like a priest than a manager," he says.