Modi's mountain to climb

- Published

- comments

Narendra Modi (centre)

On the eve of the Modi government's first budget, India is in the grip of infectious optimism.

Admittedly, doing the kind of job I do, I have been exposed to a limited cross-section of Indian society.

But the business elite I have met in Mumbai and Delhi have expressed great hopes to me that the BJP government will start to tackle some of the structural flaws in India's economy.

Admittedly, there is a degree of what you might call catch-up euphoria - in that, I am reliably told that few of the jet-setting crowd who seemed a little bit tipsy on incipient Indian change at a party last night would actually have voted for Modi's BJP (and they were scathing of him only a year ago).

But presumably Mr Modi - who in May broke the stranglehold on Indian politics enjoyed by Congress since the creation of modern India in 1947 - won't care that they are late converts.

If they put their huge wealth where their rhetoric is and start to push up India's rate of business investment - which has been flagging - that would help him achieve his hopes of reviving the growth of the economy in a sustainable way.

This is a country where growth in national income has been stuck at an annual rate of around 5% for most of the past two years.

Which may sound delicious by the mediocre growth standards of most of the rich developed world.

But given that so many tens of millions of Indians are still trapped in grinding poverty, the economy needs to expand at nearer to 8% for there to be a strong sense of social progress.

And as for living standards, they are being squeezed by inflation - especially in the price of vital basic foods - which is close to 10%.

A mark perhaps of the serious of the endemic inflation problem is that the internationally respected governor of the central bank, Raghuram Rajan, has set a target for inflation of 8% for January.

If he aimed for a rate of price rises any lower in the short term, by pushing up the cost of money, he would risk choking off what growth there is.

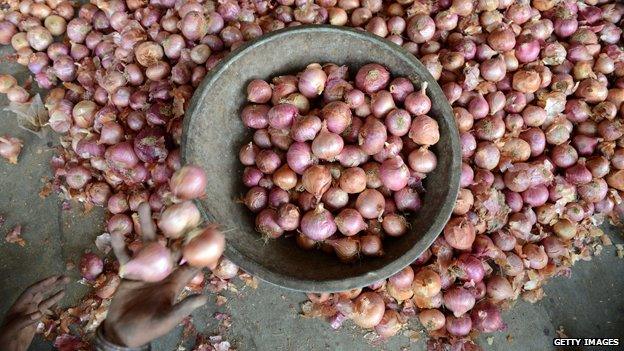

In the meantime, the government has had to resort to direct price controls, on onions recently for example, to protect vulnerable consumers.

And although India's balance of payments and government deficits are not as out of control as they were, the government's finances are still stretched, while the country is not yet paying its way in the world.

And yet India has huge structural advances - not least a huge, highly educated and ambitious workforce.

The price of onions is an important issue for the Indian economy

The question is how to unleash the potential.

For the first couple of years of Mr Modi's government, expectations are directed towards a series of reforms, few of which can be pushed through speedily.

They include an easing of restrictions on foreign investment in Indian businesses, in pretty much all industries of importance to the country's future - bar one.

Mr Modi is not expected to give any more freedom to expand in India to big overseas supermarket chains, because of the fierce opposition from millions of Indian shopkeepers that the likes of Tesco will drive them out of business (sound familiar?).

But this may be a case of avoiding short term costs to a particular commercial group at the price of losing important long term social gains, in that the needed modernisation of Indian agriculture and the supply chain would be held back.

This is a country where many still starve, agricultural practice remains inefficient and mountains of food rot and are wasted because of inadequate refrigeration in food distribution.

The big western supermarket groups can help fix all that.

Perhaps more encouragingly, the budget is expected to announce a commitment and possibly a timetable to introduce a streamlined national sales tax, a goods and services tax, to replace the myriad local sales taxes.

Walmart branch near Amritsar: Many Indian shopkeepers oppose the expansion of western supermarkets

Such a simplification should cut costs significantly for businesses that operate across the borders of India's many semi-autonomous states. And it would also reduce the pernicious incentives to smuggle goods across state borders, to take advantage of tax differentials.

However there are so many of these local taxes, and states depend on them for important revenues to such an extent, that abolishing them won't be easy.

There is also an expectation that the controversial retrospective tax on huge multinationals will go.

It is likely to be annulled only prospectively, as it were (which may seem slightly confusing for a tax that looks backward).

This means international firms could become more confident that they would not be arbitrarily whacked with a massive tax bill years after doing business in India. They could invest in India less fearful of being - in their perception - unfairly fleeced each time the government's coffers are running low.

That said, the likes of Vodafone are not likely to be reprieved from the multi-billion dollar retrospective tax bills already imposed on them.

As an Indian official said to me, the politics of being seen to cut the tax bills of well-heeled multinationals at a time of national austerity would be unpleasant for even a prime minister as popular as Mr Modi is right now.

Then there is the question of whether quantitative controls on the trading of the Indian currency, the rupee, will be lifted.

It is something the central bank would like, I am told.

But there would be risks, given that even with the current regime of relatively tight capital controls, the currency is volatile and capital flight has been a problem.

And then there is the challenge of shrinking the almost unimaginable burdens of red tape, bureaucracy and public-sector graft.

From his years as chief minister of Gujurat, Mr Modi has an impressive pedigree in that regard. But reining in India's bloated state apparatus brings the risk of alienating an official class capable of bringing India to a standstill.