Shakespeare's Globe: A theatrical laboratory

- Published

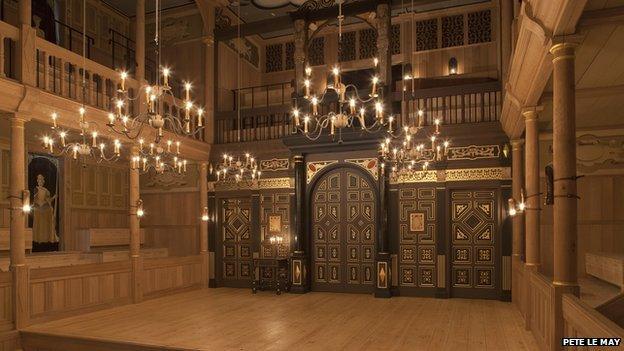

The Duchess of Malfi, by John Webster, performed in the candlelight of the Jacobean indoor theatre

When you think of a laboratory you wouldn't usually think of cheering crowds or actors in costumes.

You might not associate academic analysis with raucous outdoor performances or atmospheric indoor shows under candlelight.

But Shakespeare's Globe on London's Bankside is a kind of living laboratory, with its own team of in-house scholars, researchers and academic advisers.

Everything from the physical design of the theatre through to the individual performances is informed by the insights and research work of academics

The Globe's site beside the River Thames now has two theatres, with the opening of an indoor Jacobean theatre alongside the existing thatch-roofed, open-air playhouse.

Building this much smaller, enclosed theatre, called the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, was an academic challenge in itself.

Changing stages

Farah Karim-Cooper, one of the Globe's resident scholars, says that it's not a replica of a specific playhouse of the era, but a building assembled from different pieces of architectural evidence and contemporary sources.

Farah Karim-Cooper is head of higher education and research at the Globe

The design, a wooden candle-lit chamber, with some of the audience practically on stage, is the result of "informed, rigorous speculation, based on all the available evidence".

But this doesn't mean an obsessive interest in re-creating "authenticity", says Dr Karim-Cooper. The buildings, like the performances, are about a living, breathing engagement with modern audiences.

"We're not interested in re-enactment," she says.

But she considers the theatre an experiment in seeing how things work in practice. Like how do you move a play from the operatic scale of outdoor theatre to the close-up intimacy of the indoor theatre?

It was something that happened regularly in Shakespeare's day, taking plays from the outdoor Globe to an indoor playhouse such as the Blackfriars, built in the atmospheric ruins of a monastery on the other side of the River Thames.

It must have been like a rock band switching from a festival stage to a nightclub. The Globe was playing in daylight to open-air crowds, while the indoor theatre was a smaller, much wealthier audience, watching close-up in candlelight.

'Terrifying' darkness

The Globe team researched different types of candles, with beeswax chosen over tallow for the warmth of the light.

And in terms of lighting effects, the indoor theatre has pulley-operated candelabra - or else the actors themselves carry candles.

Thousands of schoolchildren attend free performances at the Globe each year

Light and darkness were almost characters in their own right in plays of this pre-electric era. "Darkness was a terrifying presence," says Dr Karim-Cooper.

"Darkness was palpable, something that people seemed to be able to touch, it was so thick. It was very much associated with all the horrors of the imagination, the devil, demons, witchcraft - that dark, dark world they felt was out there."

She says that if Elizabethans or Jacobeans travelled in time to modern London "their retinas would burn if they saw our levels of light".

Another big difference is that Shakespeare's audiences would have been in the same lighting level as the actors on stage.

The modern experience of an audience sitting in the dark while the stage is illuminated - a convention carried into the cinema - would have been completely unknown.

Social occasion

In the indoor theatres, audiences were paying high prices to see and be seen. The really big spenders could sit in seats at the side of the stage, where they expected to be as much part of the spectacle as the actors.

And one of the most distinctive features of plays at the reconstructed Globe is that it's impossible not to watch the audience as much as the play.

The design of the indoor theatre was pieced together from surviving buildings and contemporary sources

"It was a very social occasion," says Dr Karim-Cooper, describing the Shakespearean-era theatre as a long day out, with little precise time-keeping and much comment on who was in the crowd and the finery of what they were wearing.

"Contemporary accounts are more about the audience and who was there and what happened - more than the actual play," she says.

Putting the actors and audience in clear view of one another changes how plays would have been performed.

For instance, the great soliloquies in the tragedies become a conversation with the audience, says Dr Karim-Cooper.

'Smellscape and soundscape'

Modern audiences, in a darkened auditorium, might expect these classic speeches to be a form of introspective, interior monologue. When the audience and actors are looking into each other's eyes, it becomes a different moment.

There are other big changes between a modern and Shakespearean theatre visit.

Dark and light had great significance for an early 17th Century audience

It would have smelled very different, says Dr Karim-Cooper. There would have been a heady mix of the perfumes that were highly prized, alongside the earthy scent of thousands of people crammed in together.

Another sensory difference would have been the "soundscape", she says. It would have been a much softer sound, as Elizabethan London didn't have engines or loud machinery or amplified music.

"In terms of how loud things can get, they had no idea," she says. "There are accounts of people being freaked out by the audience clapping in a playhouse, the sound was so overwhelming. They never heard a plane taking off."

The language would have sounded unusual too. The accent of the time would have meant words such as "move" and "love" would have sounded much closer to rhyming.

And the Globe has been presenting readings of plays with the original pronunciation.

The role of the theatre's research team isn't to be trainspotters in historical accuracy but to provide practical advice for actors and directors.

"There is nothing worse than an academic who has never been on a stage, saying this is what you should do. It wouldn't work," says Dr Karim-Cooper.

Instead they talk to the performers about the plays and can research any detailed questions. They pride themselves on a quick turnaround, going to the original sources and delivering an authoritative report within a few days.

"We want to get beyond Wikipedia," she says.

She is co-editor of Moving Shakespeare Indoors, a collection of essays on indoor Jacobean theatres, and education is a key part of the Globe's work.

There is a postgraduate degree course in Shakespeare Studies with King's College, London. There are outreach projects with local schools and training events for teachers.

Every year there is a landmark schools production, the Playing Shakespeare series, with thousands of free tickets for London pupils. It's been a huge success, with many coming to see Shakespeare plays who have never been inside a theatre before.

Dr Karim-Cooper says they want to extend the idea of the theatre as a laboratory.

"We want to become a research hub. We want students to be here."

The "unique blend" will be the dramatic experimentation alongside the "literary rigour".

"We don't separate the practical from the academic."