Beauty spots still at fracking 'risk', say campaigners

- Published

- comments

Fracking licences can only be issued for beauty spots in "exceptional circumstances", according to new rules issued by the government.

It said the regulations for the new bidding round for licences - the first in six years - are stricter than before.

And companies applying to frack near beauty spots will have additional obligations.

But some environmental campaigners say the new rules are not tough enough.

Right to refuse

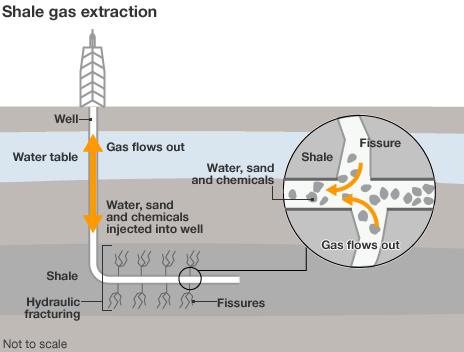

Fracking involves blasting water, chemicals and sand at high pressure into shale rock formations to release the gas and oil held inside.

Planning permission may be granted in National Parks, the Broads and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty if "it can be demonstrated they are in the public interest".

Eric Pickles, the communities secretary, will have the right to overturn planning decisions, if they don't satisfy the government's criteria.

But Greenpeace said: "In fact, so far as we can tell, the announcement actually makes it easier for developers to drill in national parks - by giving the communities secretary the automatic right to overrule local authorities who reject an application."

The National Trust gave the move a cautious welcome.

The BBC's David Shukman explains how fracking works

Richard Hebditch, assistant director of External Affairs for the National Trust said in a statement: "We welcome the new planning guidance which makes clear that applications should be refused in these areas other than in exceptional circumstances"

Forty percent of the National Trust's land is in National Parks and it owns large areas of land in other Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

"We hope it will reflect a much more cautious approach that recognises the risks of turning some of the most special places in the country over to industrial scale extraction of shale gas and oil," Mr Hebditch added.

'Irresponsible'

Environmentalists argue that the process can cause contamination of the water supply and earth tremors. The industry rejects these criticisms, claiming that the process can be done safely.

Business and Energy Minister Matthew Hancock said it would be "irresponsible" not to explore the possibilities that shale offers.

"Unlocking shale gas in Britain has the potential to provide us with greater energy security, jobs and growth," he said.

"We must act carefully, minimising risks, to explore how much of our large resource can be recovered to give the UK a new home-grown source of energy."

Energy Minister Matthew Hancock: "Some kind of recompense is very reasonable"

"Of course there is local opposition in some places," Mr Hancock told the BBC.

"But broadly there is also public support for the argument that we need energy security."

When challenged on the BBC to name a community that is in favour of fracking, he couldn't immediately identify one.

The BBC's chief political correspondent, Norman Smith, said the government has brushed aside suggestions that the announcement on national parks is designed to quell discontent in conservative MPs constituencies, especially in the south east of England.

Environmental sensitivities

But campaigners also pointed to political motives.

"Sneaking out the 14th licensing round after MPs have gone off on their summer holidays shows just how politically toxic fracking has become," said Greenpeace UK energy campaigner Simon Clydesdale.

"With MPs in Tory heartlands feeling the heat and all but seven cabinet ministers threatened by drilling in their constituencies, there could be a high political price to pay for this shale steamroller at next year's general election."

Drill down

Robert Gatliff, science director for energy at the British Geological Survey told the BBC it would still be some time before full scale drilling would start.

"The first stage, you'd review all the data you've got. Then you'd want to drill one or two exploration holes and then take samples of the shale and see exactly what the content is and see which have got the most in and which bits are likely to fracture best to get the most oil out."

An agreement to proceed with drilling would still be subject to planning permission and permits from the Environment Agency.

He said that surveys suggest there is up to 2000 trillion cubic feet of gas embedded under the UK, although "there's no way we'd get all that out."

"If you look at what happens in the US, and that's where you've got to look because that's where they've drilled thousands of holes, they're not getting more than 5%," Mr Gatliff said.

"In Britain we're so crowded and we've got these beautiful areas, that reduces the amount we can get out as well."

Tom Greatrex MP, Labour's Shadow Energy Minister, said: "With 80% of our heating coming from gas and declining North Sea reserves, shale and other unconventional gas may have the potential to form a part of our future energy mix."

But he added: "There are legitimate environmental concerns that must be addressed before extraction is permitted. Robust regulation and comprehensive monitoring are vital to ensure the public acceptability test is met."

In the UK test drilling has taken place in Lancashire and in the West Sussex town of Balcombe where last summer more than 1,000 people protested at a site operated by energy company Cuadrilla.

The north of England is the area containing the largest shale reserves.

The British Geological Survey has also pinpointed south east Scotland as containing significant resources.

Access rights

The government is keen to promote fracking in the UK, and has already announced a number of incentives to help kick-start the industry, including tax breaks, payments of £100,000 per site plus a 1% share of revenue to local communities.

It argues that shale gas could be an important bridge to help secure energy supplies until renewable energy capacity is increased.

Others argue that while it may be cleaner than coal, it is still a hydrocarbon that emits CO2 linked to global warming.

The BBC's environment analyst Roger Harrabin said: "If environmentalists succeed in stopping fracking in the UK by stirring up local objections they will actually make the greenhouse effect worse in the short term."

"This is because Britain will continue to use gas for heating and as a backup to capricious wind and solar electricity. If the industry can't get British gas it will import liquefied gas - and the energy needed to turn gas liquid makes it worse for the climate than home-produced gas."

In the US, shale gas has caused energy costs to tumble, but questions remain about whether the American shale revolution can be replicated in the UK and elsewhere.