How mobile phones became fashion items

- Published

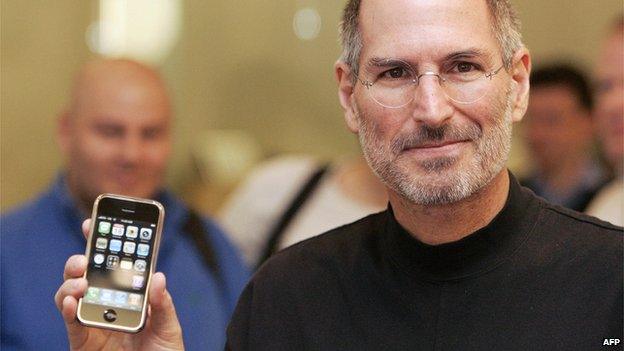

The late Steve Jobs led Apple's very successful move into mobile phones

I'm a bit slow-minded sometimes, but I'm beginning to wake up to what's happening to technology, right in front of our eyes.

It used to be something driven by engineers in laboratories, working on innovations that might take years to be turned into practical applications - the way that Teflon was a household by-product of the race to the moon.

But look what's happened now. Tech has become another fashion item, and many parts of the technology industry are now morphing into something with the expectations and rhythms of the fashion catwalk.

And very confusing it must be for companies who think they are in one business to suddenly find that all the rules of thumb they have used for decades simply don't work any more.

The current example is the mobile phone.

When commercial mobile services began 30 years ago, the wonder was the portability of something that had been on a fixed line for 100 years.

Companies who pioneered the wireless breakthrough - and who built the infrastructure to support it - took a traditional view of the investment they needed.

An initial outlay of large sums of money would result in returns rolling in for years afterwards, like an oil company investing in a new pipeline.

Motorola of Illinois, a wireless specialist for decades, was the inventor, and took a huge share of the early mobile phone market for many years.

Are mobile phones now just fashion ideas which can come and go?

But then Nokia of Finland jumped into top spot in the 1990s, and looked as if it would stay there as long as Motorola had done.

But there were hints of things to come in the early 2000s, when the Blackberry from Canadian company Research in Motion (now known as Blackberry) became an addictive business communications device partly by concentrating on email.

For "gadgeteers", there was a new top device. Utterly compelling, for a time.

Meanwhile, each new generation of mobile technology provided more bandwidth and more possibilities.

In 2007 Steve Jobs unveiled the iPhone, seizing a huge share of the mobile marketplace by stuffing a computer into the phone.

But it didn't take long for rivals to catch up - not the old players, but Samsung, which became top dog in global mobile sales in 2012, powered by a big range of phones for many marketplaces.

What is now astonishing is the speed at which mobile phone makers come and go.

It's not so much about developing technology, though of course new generations of mobile telecommunications help. The every 10-year drumbeat of a new "G" - 3G, 4G and now 5G - is beginning to get the attention of the experts who set the standards for these things.

Carry-everywhere phones are intimate devices. They are now fashion items - they express the user's personality. Newest, latest, slimmest, and shiniest become urgent point-of-purchase drivers.

And these are principles upon which it is hard to run a hardware company, making its products on expensive production lines.

Intel's successful transformation

In textile manufacturing there is still a huge amount of handwork. It enables clothing suppliers to change their run at the drop of a hat.

Nokia dominated the mobile phone industry in the latter half of the 1990s

It is much harder to respond to instant gratification when it comes to a product such as the phone.

Hi-tech companies will have to look to the catwalk to learn how to manage the fickleness of the fashion industry that they have now morphed into.

But that is hard to do. One dramatic example of a company that did manage to change its spots is the computer chip giant Intel.

Its story is told in a fascinating new book, The Intel Trinity, by the veteran Silicon Valley commentator Michael Malone.

The trinity in question was Intel's three brilliant founders. The tensions between them shaped the company as it defined the scope and growth of computer power for more than three decades.

Run by its three highly competitive engineers, Intel was an engineering company whose chips became the centre of the digital revolution.

But it behaved like an engineering company. Its products were sold to other manufacturers, and they were named by number - the first was 4004, followed in 1975 by the 8080, and then the 8085, and so on.

You had to be a fanatic to keep pace with the development.

Intel managed to successfully reinvent itself

Then something happened to computing in 1981, when IBM introduced the personal, desktop machine. Intel realised its world was changing.

The customers were no longer engineers building the chips into their computers, but the general public buying those personal machines.

Influenced, perhaps, by what Steve Jobs was doing at Apple, Intel turned itself into a consumer-facing company. It began to call its new chips by futuristic brand names, not numbers - Pentium, for example.

And it spent millions on jointly funding advertisements. The "Intel Inside" logo in print and distinctive four-note soundtrack in TV ads ensured that most of the cost of an ad was paid for by Intel, not the company whose computers were being sold.

Thus very quickly did Intel become the seventh most familiar brand name on the planet - its chips with names not numbers gave modestly informed buyers confidence that they'd bought a high-powered computer.

Intel had turned itself from an engineering company into something much more like a fashion company. It was symbolised by the gambolling operatives dressed in the characteristic Intel clean suits that became a hallmark of the company's public events.

Samsung's handsets now via with Apple's iPhone in terms of popularity

Serious-minded Intel engineers had picked up a radical change in the market for their main products - ordinary users would buy a new computer when it had a new, more powerful chip inside.

Instead of eking out a laptop for four or five years, the new home users were driven by curiosity - and fashion.

But that was slow-paced change compared to what is now happening with mobiles.

After all, smartphones are the world's first completely personalised machines. Thanks to the apps I chose to download on it, my smartphone is completely different from yours - it behaves in a very different way.

A big change from 10 years ago when one size in phones still had to fit all. How quickly we forget that sort of past. And where will this cult of fashion push us - and our technology - next?