Kabaddi gets the IPL treatment

- Published

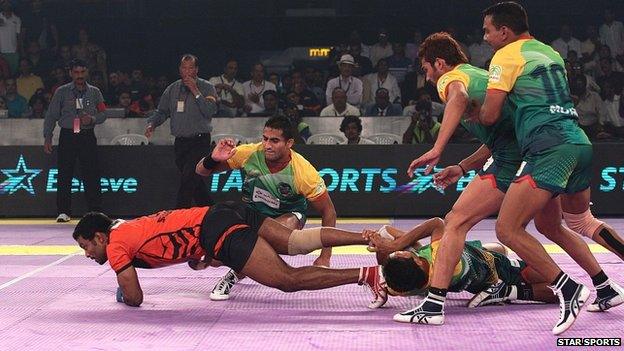

An Indian firm has launched a Kabaddi league in an attempt to raise the profile of the sport.

Growing up in 1980s Britain, kabaddi was a bit like Australian rules football - an unfamiliar sport you got an occasional glimpse of on television on a Saturday or Sunday morning.

Australian football at least had some familiar elements - a grass pitch, a ball and the occasional punch-up.

But kabaddi, where teams played on a dusty ground, diving and lunging - all while barefoot and wearing just shorts - was fascinating in a very different way.

High-paced, athletic and full-contact, it is no surprise that the players' chant of "Kabaddi, kabaddi, kabaddi" got a bit of cult status on school playgrounds across the UK.

Today many Indians still claim kabaddi as their national sport and millions play - whether informally, at school, or in one of the 4,000 or so clubs across the country - particularly in its heartland of Tamil Nadu and Punjab.

But despite requiring no equipment and very little space, in most parts of the country its popularity and profile is dwarfed by other games - especially cricket.

'Great watch'

While those playing for fun still tend to use outdoor pitches, kabaddi's introduction to the 1990 Asian Games brought an indoors version, played on a mat.

But it was not until the 2006 event in Doha that Charu Sharma got the inspiration for kabaddi's latest incarnation in India.

Eight teams compete in the Pro Kabaddi League

"So many people came up to me and said, 'The tickets are sold out, we can't get in, it's such a great watch, tell me more.'

"I knew right then it had something very special, and I wondered why wasn't it big in our own land."

Eight years on and his plan to bring kabaddi to a wider audience has just been launched. His firm Mashal Sports runs the Pro Kabaddi League, external, which sees eight teams from across India playing rounds of matches in each of the competing cities over six weeks.

It is a format unashamedly designed for television, and national network Star Sports is one of the main financial backers.

Players in bright outfits belonging to sides like the Jaipur Pink Panthers and Bengalaru Bulls enter the arena accompanied by booming music, pyrotechnics, plumes of smoke and colourful strobe lighting.

The rules have been tweaked, says Mr Sharma, to make games "more televisual" - and making some of the harder-to-follow rules more viewer-friendly.

On the opening night, VIP spectators included the actors Amitabh Bachchan, Shah Rukh Khan and Aamir Khan, as well as cricketing legend Sachin Tendulkar. More than enough glamour to distract from the fact that many of the seats lay empty despite a huge publicity blitz and modest ticket prices of just over 200 rupees (£1.78; $3).

The hope is that VIPs like Sachin Tendulkar and Amitabh Bachchan will help attract more viewers

'Guilty of glamorising'

With its razzmatazz and Bollywood backing, Pro Kabaddi has clearly taken inspiration from cricket's Indian Premier League (IPL) - the short format of the game so widely followed across the country and the globe.

"We're not in the same position as cricket, we're not that glitzy and we do not have that kind of money," says Mr Charu.

"But IPL did make us realise in our part of the world that, mere sport works well, but if you package it better, it works better.

"We're being accused of glamorising it a little bit and we're guilty - and why shouldn't we be, because most sports could use a bit of that."

What is kabaddi?

Kabaddi is a full-contact team sport originating in India

Two teams take turns to send a "raider" to the other's territory, or half

The player has to tag any one of the opposing team's four "stoppers" and return "home" within 30 seconds to win the raid

If not the stoppers win the raid

The objective is to win as many points as possible either through raiders or through stoppers

Source: World Kabaddi League

The glamour is not just about reinvigorating the sport. It is also about making a business out of it. But given that even in cricket's IPL, few teams have made any profits after seven seasons, what hopes are there for kabaddi?

At the moment the numbers are not huge. Franchisees paid up to $250,000 for the rights to run teams - money they hope to recoup through ticket sales, prize money and sponsorship.

Running costs, including salaries and travel, are estimated at $800,000 per club. By comparison, in the 2014 Indian Premier League, Delhi Daredevils paid some $1.4m just for the services of Kevin Pietersen - while an IPL franchise costs about $10m.

.jpg)

Kabaddi is traditionally played outside by players wearing just shorts

Slow sponsorship

Pro Kabaddi's backers are prepared to mop up many of up the initial costs, says Supratik Sen, chief executive of Unilazer Sports, which bought the Mumbai franchise of Pro Kabaddi competing under the name U Mumba.

He believes teams need time to build a fan base and a brand, as well as a youth development programme, which will make it appealing to advertisers. And he is confident that once businesses see the sport - and that the team owners are in for the long term - they will be interested.

"The first year is going to be about the proof - learning the mistakes, getting it very much into shape, then watch it grow."

While IPL comparisons are inevitable, he says it is an unfair one given how long cricket has grown professionally.

While kabaddi players' earnings will rise, their salaries will still be much lower than those of IPL stars

"We're a large nation and lots of companies want new things to happen. This is a game that goes right down to the grass roots in the cities and the rural areas.

"So if you're a big business - whether you're selling clothes, tractors, rice or engine oil - it's an opportunity to reach people."

Not having to wait for the financial benefits are players - drawn from across India and countries including Nepal, Bangladesh and Iran.

While once, between $200 and $500 a month was the norm for playing kabaddi, now salaries could hit $10,000, says Mr Sen - though this is still tiny compared to other sports in India.

No big names

Despite the increasing predictability of the IPL "template" being applied to other sorts - there is no sign of it abating.

There have been similar efforts with hockey and badminton - while a new two-month football league kicks off later this year.

Unlike cricket's IPL, kabaddi has few players who are household names

Alongside the usual backers from Bollywood and industry, investors include Spanish side Atletico Madrid.

"I don't think India's a country to ever reach a saturation point because of the 1.2 billion people that we have and the entire universe of sports that we have," says Indranil Blah, partner at sports agency CAA Kwan, which advises clubs and firms on sport investments.

"I can easily see six or seven new leagues for different sports being launched in the next five years. I don't know how many of them would be successful or how many of them would fail, but you can rest assured that this formula is here to stay for a while."

But he fears that where kabaddi may struggle is with the lack of household names.

"In India, for sport to be successful you need to have one role model or that one big icon. Nothing works like icons and currently kabaddi has no icons."

Expat audience

In a bizarre bit of timing, another competition, the World Kabaddi League,, external is also launching this month.

It says it is "poised to explode into the world of mainstream sport and intoxicate not just loyal fans but a whole new cosmopolitan audience… in five countries across three continents".

Interestingly its first matches are in the UK - targeting not only Indian expats who yearn to see the sport, but also perhaps those who have memories of watching kabaddi on the television all those years ago.