Mexico energy reform divides opinion

- Published

There is a point inside the Tula refinery, the main oil processing plant servicing Mexico City, that seems to perfectly capture the changing landscape of the Mexican energy industry.

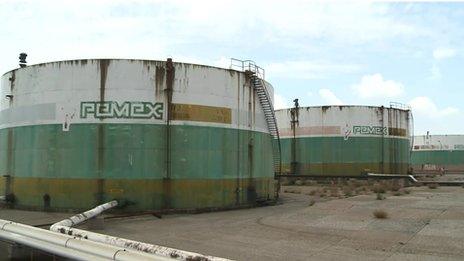

Standing atop a short metal staircase, you are flanked on one side by vast, rusting containers, capable of holding tens of thousands of barrels of crude oil. A team of men from Pemex, Mexico's state-run energy giant, is soldering the ageing tanks, part of the increasingly obsolete stock that is dotted around the complex.

On the other side is what the government hopes is the company's future.

A huge modernisation project to build a new processing plant is under way. The green and yellow pipes of the new infrastructure stand out like a facelift on the 40-year-old refinery.

Pemex's Tula refinery: the old...

...and the new

Mexican energy is on the brink of a revolution.

'Pillar of growth'

For the first time in its 76-year history, Pemex's monopoly over the country's energy industry has been broken as a reform signed into law this week opens up the sector to competition from foreign oil companies.

In an announcement on Wednesday by the energy ministry, an area worth around 20.6 billion barrels of oil will remain in Pemex's hands. The remainder will be open to private exploration with Shell, ExxonMobil, BP, and Russian company Lukoil, said to be among those lining up for the auctions to begin.

Many analysts argue that Pemex could do with a boost

Over the past decade, oil production in Mexico has fallen from more than 3.5 million barrels of crude a day to less than 2.5 million. Veteran employees of Pemex, like Jose Fernando Galvan, the senior engineer at Tula, are confident that the changes will address the issue.

"Since its inception, Pemex has been the most important company in Mexico and the stimulus for the country's development in every regard," he says, sticking closely to the company's official script on the issue. "We see this reform as a great opportunity for Pemex - a chance to continue to be the pillar of the country's growth."

Environmental pitfalls?

Miriam Grunstein, a professor at the Centre for Economic Research in Mexico City, says reform of the sector was necessary.

"I don't think we have a choice. I think the state model is defunct," she says. "I think Pemex certainly needs competition to be a fit national oil company."

Dr Grunstein says the costs of the reform could outweigh the benefits

While Dr Grunstein is broadly in favour of the reform, having seen the way other sectors of the Mexican economy - such as telecommunications - were opened up, she remains wary of the potential costs.

"The pitfalls might be environmental. We haven't been very effective environmental regulators in Mexico. The social cost of petroleum projects is also extremely important as they cause the displacement of the population from their native lands."

Economically too, there are many factors to be taken into consideration.

The huge pension liability for Pemex workers, to the tune of tens of billions of dollars, is now due to pass into public debt.

Dutch disease

Plus there are lessons to be learned from the experience of other major oil-producing nations such as Venezuela or Nigeria.

"We might get the Dutch disease, external if we get too many fiscal revenues that might depress the Mexican manufacturing industry by having too many dollars circling around the economy," says Dr Grunstein.

"The costs might outweigh the benefits if handled inappropriately. However if handled appropriately, this might really benefit Mexico, which is a country in dire need of growth."

For many, though, the questions over the reform run deeper than a cost-benefit analysis.

National identity

Opponents of reform have voiced their discontent

Mexico's state ownership of its natural resources has been enshrined in the constitution since the 1930s.

Breaking that crucial relationship, often held up as a symbol of national identity, was key to passing the changes.

On the 75th anniversary of the nationalisation of Mexico's energy industry, utility company union members and students took to the streets to protest against the changes.

Meanwhile, inside the chamber of Congress, the feelings were no less emotive, with one deputy from the left-wing PRD party, disrobing at the lectern, accusing his fellow lawmakers of stripping Mexico of its assets.

Political theatre aside, however, the response by the left has been muted and large-scale protests on the streets noticeably absent.

'Missed opportunity'

"When the government has more money, they don't know how to spend it," says PRD Senator Zoe Robledo.

He says his party recognises that Pemex needs to be modernised. But he is sceptical that this reform will bring the changes the government is claiming.

Mr Robledo believes social objectives should have been signed into the reform law

"Mexico has a lot of problems of inequality, poverty, lack of health and education in a large amount of the population. This reform could be an opportunity to tackle these issues, but it doesn't say a word about any of this. They missed the opportunity to put into the law these social objectives."

Meanwhile, the government of President Enrique Pena Nieto is pressing on regardless. On the day the president signed the law into force, his finance minister, Luis Videgaray, called the move "a true change in paradigm" for Mexican energy.

Maybe so. But the potential benefits of the new paradigm are still far from clear.

- Published13 August 2014

- Published7 August 2014

- Published9 July 2014

- Published3 June 2014