Rail fares: Why are they going up again?

- Published

Rail tickets are about to go up again - by an average of 3.5% from January 2015.

That's 1% above inflation - and will apply to all regulated fares, including season tickets.

That is unless George Osborne decides to protect passengers by limiting fare rises to no more than inflation - as he did for 2014.

The actual pounds and pence price hikes won't be revealed until Christmas time.

Why do some fares go up by more than the average that is regulated by the government?

Rail companies are allowed a little wiggle room, called "flex", which currently lets them put some fares up by as much as RPI plus 2%, as long as it is balanced out with smaller rises, or even cuts elsewhere. So you may be facing an even bigger hike than the average rise announced.

Why are fares going up regardless of the service you're getting?

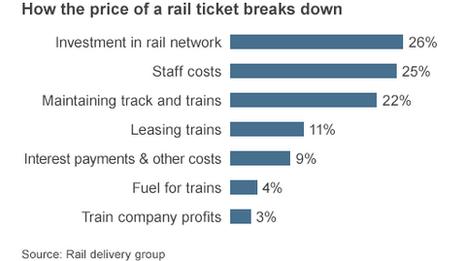

In a nutshell, the government wants passengers to pick up more of the bill for running the railways.

It all started in 2007 when a White Paper called 'Delivering a Sustainable Railway' effectively set a target to get about three-quarters of the money from fares and just a quarter from the taxpayer by 2014.

So that is why fares keep going up, and will keep going up for a while yet. The government also says it is paying for huge, multi-billion pound improvements across the network, from electrifying lines to brand new stations and trains.

If our fares are so high, why are record numbers of people using the trains?

Our regulated fares are some of the highest in Europe. But there are still lots of cheap deals out there if you can book well in advance and travel off-peak. Couple that with the cost of running a car, with pricey insurance and petrol, and the train becomes a more attractive proposition.

One senior rail executive told the BBC that, if you analyse it per person per mile, season tickets are by far the cheapest deal they offer. In fact, he said, they make a loss on them, and the fare rise goes to the government.

Higher fares are needed to pay for track improvements, says the government

Why do they use RPI and not CPI as a measure of inflation?

The Office for National Statistics has two inflation indexes - the Retail Prices Index (RPI) and Consumer Prices Index (CPI) - that measure the rising costs of goods and services in different ways.

One of the key differences between the two main indexes is that RPI includes housing costs such as mortgage interest payments and council tax, whereas CPI does not.

RPI is normally bigger than CPI, which obviously means fare rises are higher. Yet the government uses CPI for setting pension and benefit rises, for example, so the accusation is that they use CPI it when it is useful to have a smaller number; RPI when they want a bigger number.

"The use of RPI is consistent with the general indexation approach adopted across the rail industry," said a spokesman for the Department for Transport.

"The Office of Rail Regulation uses RPI as the index for Network Rail's revenues, eg Track Access Charges."

Is it the same across the UK?

No, basically.

The Scottish government says increases in regulated peak fares will be capped at RPI in January 2015. And regulated off-peak fares are frozen provided that RPI remains below 3.5% per annum.

The Welsh government has yet to decide what to do and in Northern Ireland there is no planned increase.

What would Labour do?

Labour said it would abolish the "flex" element of fare rises - which allows train operators to raise some regulated fares above the formula, providing it reduces others. But that would not necessarily stop above-inflation fare rises.

Will it ever end?

In its last command paper, the government promised to address "the concerns about rail fares and the impact they have on hard-pressed families - by ending inflation-busting increases in average regulated fares at the earliest opportunity".

That is the promise, although they cannot put a timescale on it.

- Published2 January 2013