The emergence of the counter-free bank branch

- Published

The revamped Barclays branches include self-service points

With faltering steps, an elderly customer navigates her way to the end of a queue in the bright, airy and revamped branch of Barclays Bank.

She looks at the self-service kiosks, notes the absence of traditional glass counters, spots staff dealing with enquiries via tablet computers and turns to her friend.

"It's bedlam in here," she says.

She might not be a tech-savvy, time-pressed, financially proactive customer, but she probably visits the branch twice as often as somebody half her age.

So, how can the banking industry convince her that the modern counter-free branch with more screens than staff is going to serve her better than the more traditional bank?

New uses

The British Bankers' Association, which represents the major UK banks, says there is a "revolution" taking place in UK banking. Smartphones, contactless cards and competition are changing the way customers use their bank, it says.

It points to the fact that nearly £1bn a day is transferred using the internet. Transfers using mobile phones and tablets are up 40% in a year.

But 67 million transactions a week still take place in bank branches, and the BBA says there is still a need for a High Street presence.

"While the size of these networks will decline, High Street outlets will remain important for those bigger moments, such as when a customer takes out a mortgage, wants to assess their financial options or resolve a complaint," the BBA says in a report on modern day banking, external.

As a result it is inevitable that the way bank branches look and operate will alter, it adds.

Rise of online banking

67m

transactions a week in bank branches

-

14.7m banking apps downloaded

-

£6.4bn online banking transfers a week

-

77% of customers use mobile or online banking at least once a month

Fewer staff

Such a move is referred to, in business-speak, as the "change curve" by Steven Cooper, the chief executive of Barclays Personal Banking.

He started his career as a cashier in a Barclays branch in London at the age of 16. Now, 28 years later, he has overseen the change that effectively strips away the very counters behind which he used to sit.

"I did not want a pane of glass between the customer and Barclays. I want it to be open, friendly and more comfortable," he says.

New technology has changed the bodywork of the branch, and it has altered the way the engine runs too. A more automated system ends the "soul destroying" work of processing cash and cheques, he says.

Mr Cooper has abolished his old role of cashier. Since the start of October, branch workers have been known as community bankers.

These members of staff are now seen wielding a tablet computer in branches, dealing with enquiries that cannot be resolved at the self-service counters.

Steven Cooper was a cashier at the Holloway Road branch of Barclays at the age of 16

Significantly, there will be a lower headcount at many branches. At the moment it is an average of six, but he expects that number to fall.

"This may differ from branch to branch, location to location," he says, explaining that branches need to be "agile" to local needs.

"We do need to bring costs down, but it is not driven by cost."

In the first half of 2014, there were 1,546 Barclays branches in the UK, a network that is expected to shrink.

Of course, Barclays is not alone. A whole host of UK banks are announcing staff cuts and branch closures alongside a "digitalisation" strategy.

Big banks are making changes, convinced that people will bank remotely for simple transactions, then use branches when financing bigger occasions in their lives.

Even government-backed National Savings and Investments (NS&I) - home of Premium Bonds and which uses the Post Office network of branches - says it has a mobile-first approach, as it revamps its online service.

Julian Hynd, from NS&I, says they are working on online prototypes that will also work for consumers who are "keen, but not that savvy" with technology.

With fewer visits to branches needed, banks might decide to "pop up" once a week in libraries, or via banks on wheels.

Branches past

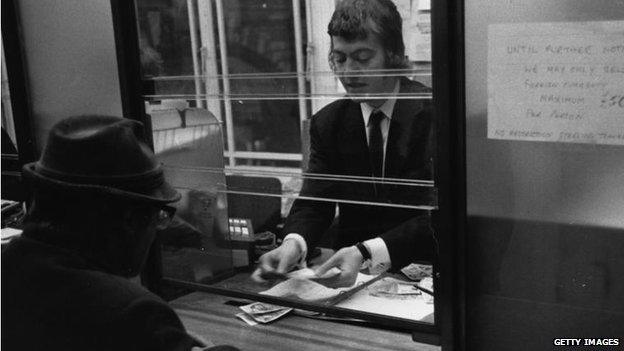

Bank cashiers have been helping customers for over a hundred years

It is all a far cry from the bank branch of the early to mid-20th Century.

Opening hours were designed to coincide with local market days, the BBA says. Inside, a line of clerks were found behind a counter surrounded by large ledger books.

It was not until the second half of the century that account numbers and sort codes were introduced and computers started to take on the work of ensuring the books were balanced.

Before the digital advance brought the cash machine, queues were commonplace, especially on Friday afternoons as people waited to cash cheques and withdraw money for the weekend, the BBA says.

Now, for many younger customers, a poor internet connection is a more relevant banking frustration than a queue in a branch.

The traditional image of bank branches is a little like this scene from the 1970s

This move online will change how banks operate and how branches look, according to Sameet Gupte, the managing director for Europe of IT company Virtusa.

"Banks are realising that Google controls more of the user experience than the banks," he says.

So banks are increasingly competing for loyalty through a customer's smartphone, he explains. The company has developed software that allows customers to pay in money by sending in a photo of the cheque and Mr Gupte expects many more remote payments like this in the future.

"The digital wallet will blur the line between a bank and a retailer," he predicts.

In practice, that means a bank may remind customers, via a smartphone, to pick up the groceries on a specific day - automatically ensuring their payment system is used when the phone is tapped on a reader in the store. It will also warn the customer, for example, if their account is short of funds for their typical weekly shop.

So, does this make the branch redundant? He says that branches could encourage loyalty to the bank and local businesses by offering discounts when it recognises that the customer (and their smartphone) are in the area.

It may also encourage customers to pop into the branch, as a one-stop financial shop. Given the location of branches in prime retail territory, they will increasingly share premises with coffee shops and other retailers, says Mr Gupte.

A latte is a long way from a ledger - but it might just become a more common sight in the bank branch of the future.