Innovate or die: The stark message for big business

- Published

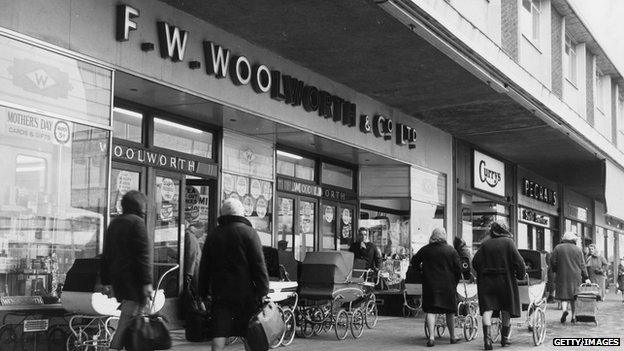

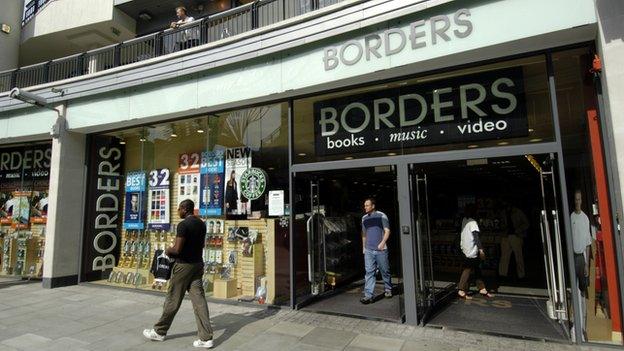

Retailers who fail to respond to changing technology go to the wall

Big companies that fail to innovate risk extinction. That's the stark truth in the era of "digital disruption".

Just look at the likes of Woolworths, Polaroid, Alta Vista, Kodak, Blockbuster, Borders... the list goes on. All steamrollered by strings of ones and noughts and changing consumer behaviour.

But why are so many big companies so bad at it?

"Typically, big companies are much more conservative than start-ups and won't do anything that is untested or could risk future profits," says George Deeb, managing partner at business consultancy Red Rocket Ventures.

"Innovation efforts really require a very different, more entrepreneurial risk-taking mindset."

Jackie Fenn, a specialist in innovation at research consultancy Gartner, told the BBC: "Size can add to the challenges. A strong brand can have a fear that failure may damage its reputation.

"But you cannot afford to stay still - business is a moving escalator. The world is moving around you - customer expectations are changing, competitors are always catching up and threatening to take away your business."

Polaroid pioneered instant cameras from the 1940s onwards but was undone by digital photography

Short-termism

Big publicly quoted companies also have quarterly earnings and shareholder expectations to meet, says Mr Deeb. This can take the focus away from research and development (R&D) and on to earnings and profits.

Exponential-e is a cloud and internet service provider with an annual turnover of about £60m. Its founder and chief executive, Lee Wade, used to lecture on innovation and agrees that short-termism is a major problem.

"[Big companies] are not adept at monetising ideas because they're so focused on delivering short-term performance to meet City shareholder demands," he says.

Lee Wade, chief executive of Exponential-e, thinks big firms are too short-termist

Another reason is that innovative companies often have a forceful, passionate entrepreneur at the helm, he adds, but when that person leaves or dies, the company can lose momentum.

"Tesco was one of the greatest British innovators under [Sir] Terry Leahy," he offers by way of example. "Now they're losing out to the likes of Aldi and Lidl.

"Apple's Steve Jobs was the hardest taskmaster and a ruthless visionary. But this is what you need to drive innovation."

Growth engine

So how can big companies avoid becoming innovation laggards?

Venerable engineering company General Electric (GE), a global powerhouse with revenues of about $150bn (£91bn) and a market capitalisation of nearly $265bn, has built innovation into every part of its business, says Todd Alhart, director of media relations for GE Global Research, the group's R&D subsidiary.

With centres around the world employing thousands of researchers and engineers serving all of GE's divisions, you might think the company had innovation covered.

But Mr Alhart says: "We have a tremendous amount of investment in engineering, but the world is moving a lot faster. So we know we've got to be faster. The digital world is increasingly becoming part of the physical world."

So GE has been experimenting with "open innovation", inviting external engineers to take part in design competitions.

This winning design for GE reduced the weight of a jet engine bracket by 84%

"We're trying to reach out in a more open and collaborative way," says Mr Alhart.

For example, in 2013 GE challenged the GrabCad engineering community to come up with a way of 3D printing a lighter, stronger bracket for its jet engines.

"We had about 700 entries and gave out prizes for the best ideas," he says. "A young student from Indonesia reduced the weight by 84%. It's a great lesson in how you can get great ideas fast."

Outsourcing innovation this way is definitely the trend, says Phil Cox, president of Silicon Valley Bank's UK branch.

"Facing dual pressures of the cost of innovation and the speed at which the innovation economy is changing, large organisations are increasingly embracing open innovation.

General Electric, which produce gas turbines like this, is a firm believer in "open innovation"

"By partnering with other organisations, from academics to early-stage businesses, larger companies are able to introduce new products and strategies more easily and rapidly."

More than a bank?

Barclays Bank is a case in point.

It has set up an Accelerator centre in Whitechapel, east London, in partnership with Techstars, the start-up investment and mentoring company. Of 340 companies that applied to join the accelerator programme, 11 were selected.

"We wanted to partner with the entrepreneur ecosystem," says Derek White, the bank's chief design officer. "We now have an engine for capturing technology, implementing and promoting it. This is about inventing the future of financial services."

Borders was another traditional retailer that was a victim of "digital disruption"

The bank also has its own internal start-up programme expanded after the successful launch of person-to-person mobile payment platform Pingit in 2012. There are now 40 business ideas in development, says Mr White.

"Launching Pingit would normally have taken two or three years - it actually took just seven months," he says.

The secret is designing products around customer need, prototyping rapidly, keeping teams small and agile, and having daily, not weekly, meetings, he maintains.

"A large corporate doesn't have to behave like a large corporate."

It's a gas

In another example, Centrica-owned British Gas, a former nationalised monopoly and the largest UK energy company with about 10 million domestic customers, has traditionally been concerned with holes in the ground, pipes and wires.

But with the arrival of smartphones, smart meters and smart thermostats, it had to act quickly or lose out to imminent competition from the likes of Nest, which makes smart devices for the home, and other newcomers.

Like Barclays, it adopted the start-up approach and created Hive, its smart-metering subsidiary.

Kassir Hussain, director of connected homes at British Gas, says Hive was founded on the "lean start-up principles" espoused by Eric Ries in his book The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses.

In practice, this means developing a product or service step by step, constantly consulting with customers so that money isn't wasted on features they will not want. Each stage of development is tested - so-called "validated learning" - so that future success is almost built in to the process. Normal management structures don't apply.

The British Gas Hive subsidiary was founded on "lean start-up" principles

"We believe that job titles can actually prevent co-operation and teamwork," says Mr Hussain. "It's about encouraging an entrepreneurial mentality throughout the business. Hive's product development is in days and weeks, not months and years."

Hive's Active Heating system, which lets you remotely control your home heating via smartphone, now has about 80,000 customers. But the service could not have come about from within British Gas's complex corporate structure, Mr Hussain believes.

"Nearly three-quarters of Hive's business is staffed by people with digital backgrounds from outside the group," he says.

'Two pizza' teams

Perhaps it is online retailer and web services provider Amazon that best exemplifies lean start-up principles in action.

Keeping teams small enough to be fed by two large pizzas, giving them autonomy and direct access to customers, encourages risk taking and innovation, says Ian Massingham, technical evangelist for Amazon Web Services (AWS), the retailer's cloud platform.

"AWS has launched 280 new services and features this year - it's all about making things better for our customers."

Most commentators accept there is no one way for big companies to innovate, but they all agree that without innovation your days at the top could be numbered.