ECB’s last roll of the dice

- Published

- comments

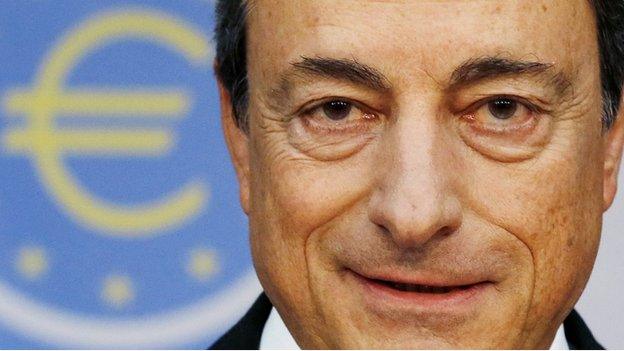

ECB president Mario Draghi said the bond-purchase initiative is a break from the bank's history

Today is a big day in the history of the eurozone, for three reasons (always good to have the big three).

First an ideological Rubicon has been crossed by the European Central Bank (ECB) - because in trying to cut interest rates and increase the supply of credit in a stagnating Europe, it is engaging for the first time in a form of quantitative easing.

For the avoidance of confusion, its QE will be purchases of private sector bonds - what are known as asset backed securities - rather than government bonds.

But as the president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, said in his press conference today, this bond-purchase initiative is a break with the ECB's history, in the sense that the bonds are being bought rather than pledged to it as collateral for cheap loans.

Risk transfer

The significance, as I am sure you don't need telling, is that the risk of the bonds or private sector loans going bad will transfer to the European Central Bank when it buys such bonds, rather than (as hitherto) simply holding them as security.

Or to put it another way, eurozone governments - and the German government in particular as the biggest shareholder in the ECB - will now be taking the risk of lending to businesses and (presumably) households, and will incur losses if the loans are not repaid.

Eurozone governments - especially the German government - will take on ECB risk from bonds

For the fiscal conservatives of the German establishment, this is a big and bitter pill to swallow.

So how much of eurozone taxpayers' money will in effect be put at risk?

Well, Morgan Stanley calculates that there is 690bn euros of eligible bonds in issue for the ECB to potentially buy. And it expects the ECB to buy up to 15% of this, when the programme starts in October.

So, initially at least, the ECB could spend up to around 100bn euros.

The second reason today's announcements matter is that the European Central Bank has now almost exhausted its ammunition for preventing the eurozone sliding into a devastating deflationary, contractionary spiral.

It also cut interest rates today.

So its main rate for lending to banks is now just 0.05%, which is zero plus the price of a stale croissant.

That derisory 0.05% is the rate at which it will lend to the eurozone's banks in its so-called Targeted Long Term Refinancing Operation, which it announced earlier in the summer.

So if Morgan Stanley (again) is right, the ECB will eventually lend up to 650bn euros to banks at an interest rate of more-or-less nil. And in case you forgot (surely not), all this money is supposed to be passed on to Europe's small and medium size businesses.

If the eurozone's banks won't lend to businesses when they are being flooded with free money by the ECB, then either a shortage of credit is not the eurozone's fundamental problem, or there is no hope for the eurozone.

The ECB has almost exhausted its options for preventing eurozone deflation

For what it's worth, the European Central Bank has also increased the penalty interest rate it charges banks for depositing their cash with it from minus 0.1% to minus 0.2%.

And (to rework my previous point) if eurozone banks still prefer to park their cash with the ECB than lend it out, then what's wrong with the currency union is probably beyond the ECB's powers to fix.

Which brings me to the third reason why what the ECB has done is so important.

Money injection

There is one more further initiative it could take, which I signalled earlier - namely it could engage in QE involving government bonds, or purchases of the debts of governments, from France, to Spain, to Belgium, Germany and the rest.

Draghi said that the ECB's board was unanimous that this option should be explored and developed.

But goodness only knows whether the Germans will agree to it, as and when it comes to the moment of truth - since it would represent, for many Germans, an unlearning of the most painful lesson in its monetary history, namely the hyperinflation of the early 1920s.

However some would say it is almost irrelevant whether the ECB finally goes for QE (almost but not completely irrelevant), simply because that is all that's left for the central bank, in its mission to ward off a Japanese style semi-permanent slump.

The implication, which Draghi did not shirk, is that eurozone governments now have to start being brave, if the eurozone is to revive in a serious and sustainable way.

He wants them to liberalise product and labour markets, not shy away from their commitment to strengthen their public sector finances, but simultaneously finance supposedly growth-spurring tax cuts with public expenditure cuts.

Eurozone 'doomed'

Draghi would feel these economic reforms and fiscal consolidation are long overdue.

So what he has announced today should - perhaps - chill the marrow of governments in Rome and Paris, which have been dragging their feet on shrinking their respective states and challenging supposedly inefficient working practices.

Draghi has in effect said they - and the whole eurozone - is doomed, if they don't challenge powerful vested interests that stand in the way of what he sees as economic modernisation.

Or to summarise why today is momentous, the European Central Bank has reached almost the limit of what monetary policy can do to save the eurozone.