What makes a global top 10 university?

- Published

MIT is the highest rated university in the world for the third year in succession

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is in first place in the latest league table of the world's best universities.

It's the third year in a row that the US university, famous for its science and technology research, has been top of the QS World University Rankings.

Another science-based university, Imperial College London, is in joint second place along with Cambridge University.

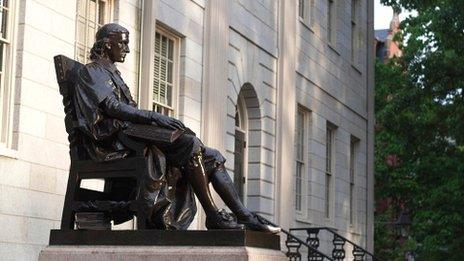

Behind these in fourth place is Harvard University, the world's wealthiest university. And two more UK universities share joint fifth place, University College London and Oxford.

With King's College London in 16th place, it means that London has three institutions in the top 20.

Edinburgh University is joint 17th and there are two Swiss institutions, ETH Zurich and Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, in this top tier.

But US universities are still in the majority, taking 11 of the places in the top 20.

Even though some university leaders might be sceptical about such rankings, they will all be sharply aware of their significance.

Mike Nicholson, Oxford University's head of admissions, says: "It's fair to say that it would be a foolish university that did not pay close attention to how league tables are constructed."

Rankings have become an inescapable part of the reputation and brand image of universities, helping them to attract students, staff and research investment.

No university website is complete without the claim to be in the top 100 for something or other.

How to be top

But what is perhaps more surprising is that they are a relatively recent arrival on the higher education landscape.

This is only the tenth year of the QS rankings and the earliest global league table, the Academic Ranking of World Universities, produced by the Shanghai Jiao Tong University, was first published in 2003.

Imperial College London has risen to second place in the global rankings

They have risen alongside the globalisation of higher education and the sharing of information online.

But how does a university get to the top of the rankings? And why does such a small group of institutions seem to have an iron grip on the top places?

The biggest single factor in the QS rankings is academic reputation. This is calculated by surveying more than 60,000 academics around the world about their opinion on the merits of institutions other than their own.

Ben Sowter, managing director of the QS, says this means that universities with an established name and a strong brand are likely to do better.

The next biggest factor - "citations per faculty" - looks at the strength of research in universities, calculated in terms of the number of times research work is cited by other researchers.

The ratio of academic staff to students represents another big chunk of how the rankings are decided.

Big brands

These three elements, reputation, research citations and staff ratios, account for four-fifths of the rankings. And there are also marks for being more international, in terms of academic staff and students.

"Academic reputation" is the biggest single factor in these rankings

As a template for success, it means that the winners are likely to be large, prestigious, research-intensive universities, with strong science departments and lots of international collaborations.

Is that a fair way to rank universities? It makes no reference to the quality of teaching or the abilities of students?

"We don't take an exhaustive view of what universities are doing," says Mr Sowter.

"It's always going to be a blunt instrument," which he says is both the strength and weakness of such lists.

Immigration points

The overall effect of a decade of such league tables has been beneficial, Mr Sowter argues. It has made universities take a closer look at themselves to see how they compared with rivals.

There always were "unwritten league tables, based on stereotypes," he says, so having some more transparency allows a more open debate.

.jpg)

The ratio of academic staff to students counts towards rankings

But the creation of such a ranking has a dynamic of its own - and Mr Sowter says there have been unintended consequences.

"Some fixate on it too closely," he says. Improving their ranking position has been written into the mission statements of some universities.

It has also taken on a quasi-official status. Denmark's immigration system gives extra points to graduate applicants according to how high their university is ranked.

The pressure to get up the ladder has also pushed some universities into trying to bend the rules, says Mr Sowter, with incorrect data being submitted.

The Times Higher Education World University Rankings, ahead of its annual rankings next month, has been even more specific about what constitutes a top-200 university.

It includes an annual total university income of above $750,000 (£462,000) per academic; a student-staff ratio of almost 12 to one; about a fifth of staff and students are international and research income of about $230,000 (£142,000) per academic.

"You need serious money, it is essential to pay the salaries to attract and retain the leading scholars and to build the facilities needed," says THE rankings editor, Phil Baty.

Multi-ranking

Regardless of how they are calculated, there is a seductive simplicity to rankings.

"The rankings, for better or worse, have been highly influential with students and also with governmental leaders and some universities in various countries," says Philip Altbach, director of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College.

The OECD's Andreas Schleicher wants rankings that compare what students learn

But he cautions on what is actually being measured. Should non-research universities be compared in rankings designed for research-intensive universities?

An attempt to create a different type of university comparison has been launched this year by the European Union, with the U-Multirank project.

This puts less emphasis on reputation and allows students to select their own criteria to make comparisons.

The idea is that a student wanting to find an undergraduate arts course isn't really going to learn much from rankings driven by international science research projects.

There could be another entirely different way of comparing universities on the horizon.

Andreas Schleicher, the OECD's director of education, who has pioneered Pisa tests at school level, wants to begin comparisons in higher education.

He says there is a public demand for assessing the quality of universities.

But rather than looking at what goes into universities - such as money, staff and facilities - he wants to find out more about the output in the form of what students are learning.

Proposals for a different kind of university ranking will soon be put to OECD governments, he says.

It's not difficult to see the limitations of university rankings. They measure the attributes of the university rather than its students. They produce a list dominated by a certain of type of institution. Small, specialist, arts-based colleges are going to suffer regardless of their quality.

Those that focus on teaching rather than research will not be as recognised. The emphasis on reputation will reinforce the advantage of those that are already famous. And the top tier of these global rankings is exclusively filled with English-speaking universities.

But such lists still exert an undeniable, attention-grabbing appeal.

"The fact that people argue about league tables is a trigger for change," says Mr Sowter.