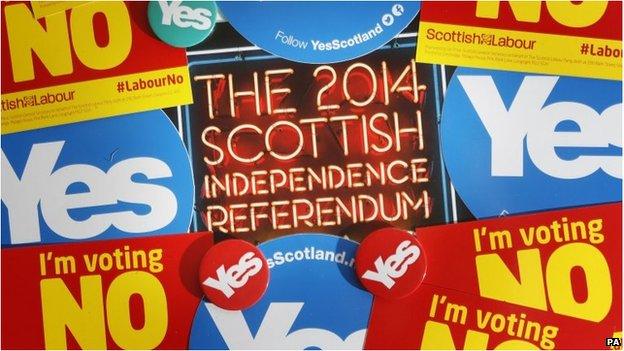

What price Scottish independence?

- Published

- comments

Here is just one illustration of why assessing the economic impact of Scottish independence on Scotland and on the rest of the UK is so difficult - and why sterling has been weakening as the probability of Scots breaking away has increased.

On the one hand, it is very likely that a slug of Scotland's financial services industry will relocate to London if Scotland votes to separate from the UK (yes, I know many would say that would be good for the rest of the UK - bear with me please).

As I have mentioned before, Royal Bank of Scotland would announce an intention to move its home to England as and when a yes vote is declared (and I have just had it re-confirmed that RBS has a contingency plan to emigrate south of the border).

Uncertainty

It would feel obliged to do that, because of the risk that those who lend to it would withdraw their funds over the many months of uncertainty about who would be its lender of last resort (or the provider of emergency finance in a crisis), about who would regulate it and about what impact Scotland's choice of currency would have on the bank's financial strength.

The point is that lenders to banks, including ordinary depositors, have a choice about where to place their money. And many of them will take the view that there is no point leaving cash in RBS when there is a greater than average degree of uncertainty about that bank's long term prospects.

It is not that independence would definitely be bad for RBS. It is simply that creditors don't like uncertainty.

So RBS will knock that uncertainty on the head by turning itself into a rest-of-UK financial institution rather than a Scottish one.

DUK, BUK, SUK?

Now, as I've said, if RBS were to move to England, that would probably be seen to be good for the rest-of-UK's economy and also its balance of payments, and detrimental to Scotland.

And before I move on, yes I too hate this "rest-of-UK" moniker, but surely saying England, Wales and Northern Ireland each time is even more cumbersome; so if independence does happen, will we be able to revert to UK for what remains, or perhaps we will become DUK for diminished UK, or BUK, for broken-up UK, or SUK, for smaller UK?

Anyway, if other Scottish financial businesses were also to relocate southerly in a similar way - Standard Life has disclosed contingency plans to move at least some of its operations to England - that too would be seen to be positive for the UK minus Scotland.

So why has sterling been dropping, if Scottish separation could strengthen the rest-of-UK economy?

Well it is because if financial services travel in one direction, oil would travel in another.

And it is much easier to see, in the short term at least, how the loss of oil to the rest of the UK would significantly worsen the balance of payments - whereas the positive impact of gaining RBS et al is much harder to judge.

Better

Here are some back of envelope sums I have done.

Last year, the whole UK's current account deficit - the gap between the income it receives from the rest of the world and what it pays the rest of the world - was a high 4.4% of GDP. And this deficit reached a painful 5.7% of GDP in the last three months of 2013, which was its highest level since proper records started to be compiled in the 1950s.

Now you might have expected this to lead to some kind of sterling crisis.

It did not for a few reasons.

First, the UK's underlying trade performance has been improving a bit.

Second, a big cause of the growing deficit was a fall in income earned on assets we own abroad, especially in the eurozone - and there is an expectation (perhaps a naive one) than in time this income will bounce back.

Third, the stock of assets owned by the UK in the rest of the world exceeds the value of what we owe the rest of the world, according to an analysis by the Bank of England. So in theory we can finance this current account deficit for some time, by selling assets (if need be).

But what would happen to the current account deficit of the rest of the UK if an independent Scotland were to get 90% of oil and gas assets - which is the expected carve up were Scotland to break away?

Not pretty

Well I calculate the current account deficit for the rest of the UK in 2013 would have been 6.9% of rest-of-UK GDP (and for the avoidance of doubt, I have allocated to Scotland a proportionate share of the UK current-account deficit, before adjusting for the oil transfer).

Now a current account deficit of 7% odd cannot be comfortably ignored for long, and it would have been hard for investors to shrug off. Doubts would have been fomented about the UK's ability to pay its way in the world and to finance its way of life.

We might have seen an old-fashioned run on the pound.

However that is to look backwards of course. And the whole UK balance of payments has been improving this year (a bit) while the value of oil exports has been been falling (also a bit). So the picture doesn't look quite so grim - though it is still far from pretty.

Now in a world of perfect information, I would be able to tell you what the rest of the UK's balance of payments and current-account deficit would look like, adjusted for an increase in financial services revenues (from the migration of RBS and pals) and a decrease in oil exports.

Sadly we live in a world of data imperfection.

And of course there is yet another uncertainty, in that we don't know which other businesses would migrate north or south of the border, of their own free will, in the event of such a huge constitutional change.

Fog

What we do know (yes we do) is that investors don't like heightened degrees of ignorance about the economic outlook. And they demand a high price for their money when lending and investing in countries where the outlook is hidden by fog.

So in a UK whose prospects are shrouded, sterling is likely to fall some more, and - the really irksome thing - the cost of capital for borrowers north and south of the border is likely to rise.

Which would mean businesses would invest less and consumers would spend less for just as long as it was impossible to see the shape and strength of the rest of the UK's economy and that of Scotland.

Such expensive uncertainty may persist for just a few days till September 19, the day after the vote, if the Scots were to vote to stay in the UK. In which case the damage to our prosperity would be transient and small.

Steep price

Or it could persist for 18 months or much longer, depending on how long it takes to negotiate the separation of the Scottish economy from the UK's.

You don't need telling, I know, that the longer the uncertainties persist, the more prolonged the UK will suffer from an elevated cost of finance, and the greater the harm there will be to economic growth - both sides of the border.

Or to put it another way, whatever the long term prospects for Scotland and the rest of the UK, both could pay a steep and immediate economic price, during the months and probably years it will take to firmly determine the distribution of assets north and south (and I haven't even got on to the further complications of determining how liabilities, such as the national debt , are shared).