The start-up rejected by investors 45 times in a row

- Published

Nick Hungerford knows a few things about dealing with rejection.

In 2010, the 34-year-old Englishman was going to meeting after meeting in California's Silicon Valley, trying to secure funding for his business idea - Nutmeg, an online-based investment management business.

And the first 45 wealthy investors he pitched to all said no.

"It was horrible," he says. "The feedback was very personal.

"Some investors said they liked the idea, but that I couldn't do it. Others said they didn't like the idea, and some simply said I wasn't good enough.

"It was really brutal, I hugely questioned myself."

At the time Mr Hungerford, who was in Silicon Valley after completing a Master of Business Administration from nearby Stanford University, was sleeping on the floor of a friend's house, and working out of his garage.

"I was living the entrepreneurial dream that had turned into a horrific reality," he says.

It was the autumn of 2010 at this point, and Mr Hungerford was running out of money, maxing out his credit cards to cover his living expenses.

He says: "I drew a line in the sand, and said that if I haven't got a 'yes' by December I would go and get a job."

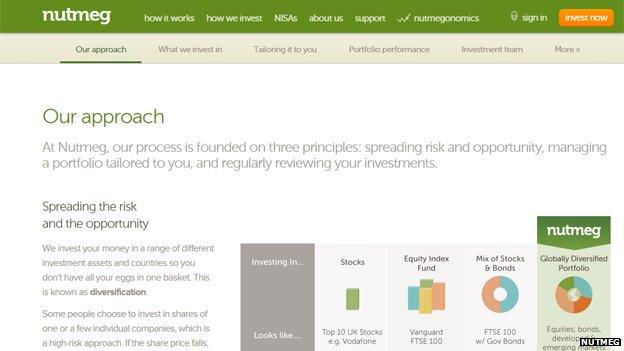

Nutmeg says its online model allows it to significantly undercut its larger, more traditional rivals

'Vindicated'

Then Mr Hungerford secured another investment meeting, his 46th, this time with a man called Tim Draper.

Mr Draper may be little known outside of technology circles, but he was an early investor in Hotmail and Skype, and is worth an estimated $1bn (£620m).

After listening to Mr Hungerford's pitch, Mr Draper was quick to say yes. Other wealthy investors soon followed suit.

"I felt so vindicated," says Mr Hungerford.

Silicon Valley bigwig Tim Draper was the first person to invest in Nutmeg

With "tens of millions of dollars" now behind him, he never did need to look through the job advertisements.

Instead, he was able to start Nutmeg in early 2011, choosing to return to the UK to launch the firm in London.

Nutmeg itself is an investment management business. You give it your savings, and it will invest them on your behalf in everything from shares to property, and bonds to currencies.

While there are thousands of such firms around the world, Nutmeg's difference is that it claims to have been the very first to base itself online.

Bosses of the UK's largest banks and investment firms have been to meet Nick Hungerford

So instead of having to phone your investment manager at some big bank in the City of London, or relying on a statement sent to you in the post every six months, you simply log into Nutmeg's website, and you can instantly see your portfolio and how it is performing.

Disruptive companies

By Brian Morgan, Professor of Entrepreneurship, Cardiff Metropolitan University

In analysing small business growth it is sometimes useful to distinguish between "lifestyle firms" and "growth firms".

The former are set up by individuals who prefer being self-employed to working for someone else, but are essentially looking for a stable income.

Growth firms, on the other hand, such as today's successful online firms, are founded by traditional risk-taking, innovative entrepreneurs.

They respond positively to new opportunities and incentives to undertake risk, and they are focused on process and product innovation.

Joseph Schumpeter - a famous inter-war economist - described these growth firms as the agents of "creative destruction".

For him they were the bedrock of modern capitalism - introducing a stream of innovative products and services that would destroy many existing businesses and, in their place, create new ones.

'Democratise investing'

Because of its online model, and the fact it has a modest office in south London rather than an expensive one in the City, Mr Hungerford says Nutmeg has significantly lower overheads than its larger, more traditional rivals.

As a result, he says it charges substantially lower annual fees - as low as 0.3% compared with an industry average of 1.37%.

Nick Hungerford: We distribute investment through the internet

At the same time, people can invest just £1,000 with it, as opposed to the minimum of £500,000 with many large investment management firms.

Mr Hungerford says: "Historically this industry was only open to the very wealthy, but we want to democratise investing, to open it up to far more people."

He adds that he wants Nutmeg to do to investing what Amazon did to online retailing - to grow to dominate the marketplace, and be available to everyone.

After two years of development work, Nutmeg opened for business in January 2013, and now has more than 35,000 customers, and is one of the fastest growing financial firms in the UK.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, at least six companies around the world have now followed Nutmeg's business model, while the big banks have been keen to find out more.

Nutmeg has a small office in south London to keep its overheads low

Mr Hungerford says: "Pretty much every chief executive of a big bank or big asset management company [in the UK] has come in to see us, to find out more about us, and what we are up to."

Yet he adds that "the big incumbents are reluctant to follow our model because they are making so much money" just targeting the super-rich investor.

'Great parallel'

Born in Bristol, and brought up just outside Bath, Mr Hungerford is the son of a vicar and a nurse.

He says he got his love of finance from his grandmother, who gave him investment books "when he was eight or nine".

After gaining a degree in economics from Exeter University he moved to London, where he worked in investment banking for Barclays and Brewin Dolphin for seven years.

Eventually, determined to set up his own company, Mr Hungerford quit his job, and went to Stanford, where his idea for Nutmeg took shape.

But where did the unusual name come from?

"We tested 519 names over six months," says Mr Hungerford. "We eventually chose Nutmeg because it used to be the most valuable spice in the world, wars were fought over it. And of course now it is available to everyone, which is a great parallel."

He adds that Nutmeg now plans to continue to focus primarily on the UK market. Any future expansion to the US will only be possible when an American regulatory change allows such investment firms to operative via the internet.

"I could have stayed working in the City, but I realised I wasn't particularly fulfilled with my life," says Mr Hungerford.

"I got the entrepreneurial bug, and decided I needed to go to business school to learn how to run and grow a business. I wanted to try to be the person that I dreamed I could be."