How Dundee became a computer games centre

- Published

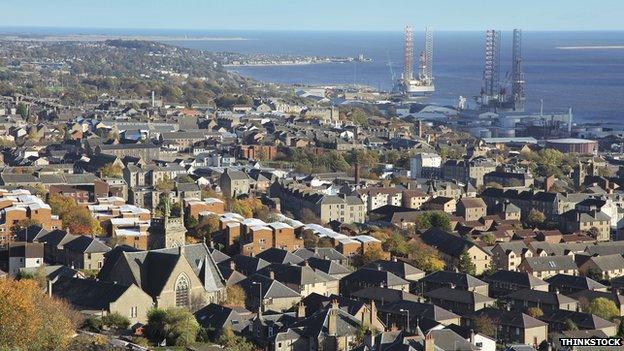

The city of Dundee has been home to a number of economic clusters

How do you create a cluster: a town, city, or region where businesses of a particular kind root, grow and may - eventually - become globally significant?

Many countries would love to know. Does this Silicon Valley kind of process happen by accident or design?

History tells us lots about this. Often it starts with people, or raw materials.

The world's largest textiles industry began in Lancashire in the late 18th Century, when new raw cotton imported from the US into Liverpool could be processed and manufactured into cloth using water power from the Pennines, and then steam power generated from local coal.

It was a combination of events which clever inventors of looms and spinning machines then turned into an industrial revolution, employing thousands of people in the dense Lancashire mill towns which sprang up in the 19th Century.

Far away in Michigan, the small city of Grand Rapids became the furniture capital of the country at the start of the 20th Century. This outburst of manufacturing activity was based on the wood brought down from the hills to be cut into lumber before transportation on the Great Lakes.

Though cheap imports have replaced most domestic furniture making in the US, the world's three biggest office furniture makers - Steelcase, Herman Miller and Hawarth - still have their headquarters within an hour's drive of each other in Michigan. An eye-catching concentration of effort.

That's a cluster. The other day I encountered another one, in Scotland, one with an intriguing timeline attached to it. And some happy accidents.

Home of the Spectrum

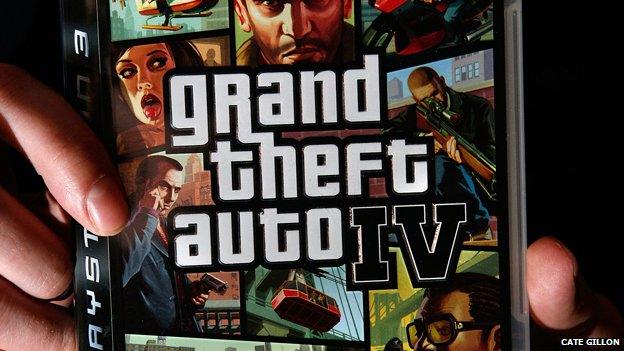

On the face of things, it seems rather odd that the world's biggest-selling video game - Grand Theft Auto - started life in Dundee. But there's an economic logic to the way that in 20 years the Scottish city has become a notable cluster for the world video games industry.

The man who told me all about this is Chris van der Kuyl. He was born and brought up in Dundee, and he is now one of the top dogs in the games industry, chairman of 4J, a company that is heavily involved in developing the already huge-selling game Minecraft (originally from Sweden) for computer consoles.

The computer game Grand Theft Auto has its origins in Dundee

The Dundee he grew up in was one in which many people in the 1980s were already computer savvy.

When Clive Sinclair, later Sir Clive, launched his home computer called the ZX Spectrum in 1982, Dundee was where it was assembled in a factory owned by US watchmakers Timex. The Spectrum price was £125, or £145 with extra RAM.

Timex (then the Time Corporation) had come to Scotland in 1946, lured by new post-World War Two Scottish regional development grants, when the jute (a natural fibre) industry was already in decline and jobs were at a premium. The Dundee plant eventually closed after a bitter strike in 1993.

And in the days before Bill Gates created mass-manufactured operating software, if you had a computer you had to learn how to programme it. And create your own games. A small generation of computer-literate young people was born.

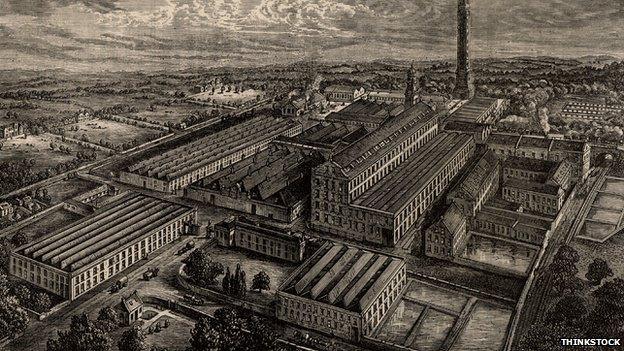

Most jute is now processed in India and Bangladesh

In Dundee, home computers were very accessible. People such as Chris van der Kuyl learnt to use them at an early age. Many went on to study computing at Dundee Institute of Technology, the forerunner of Abertay University, and at the University of Dundee.

People who had used computers from childhood grew up wanting to do things with them as grown-ups. They formed teams, invented games, and brought in the expertise to make them real and compelling to purchasers and players.

Outsiders and non-gamers really took notice when David Jones started a local company called DMA, which produced a compelling best-selling game called Lemmings in 1991. Games began to be seen as a serious business.

Leap of faith

The city had of course been an industrial cluster for decades, famous for the three Js: jam, jute and the journalism of the idiosyncratic DC Thomson family firm, inventors of the Dandy and Beano comics, and the Sunday Post newspaper.

Processing jute took hold in Dundee in the 19th Century. Dundee was a whaling city, and it was discovered that jute from India could be processed by machine if first treated with whale oil.

Jute was the main employment: at the end of the 19th Century there were 100 mills employing 50,000 workers, mainly women. Even in the 1960s the clatter of looms was still one of the sounds of the city, but the industry was in sharp decline, defeated by foreign competition.

Dundee's former jute industry was once a huge employer in the city

In eventual reaction to the decline of industrial Dundee, locals turned to what had then become Abertay University with a suggestion: start a department for the study and teaching of computer games, complementing the established computer science department.

It must have been a leap of faith, taken by academics and administrators who were personally removed from the dubious lure of video games, and the teenagers whose waking hours were taken up playing them in back bedrooms.

But this was what was called as far back as 1902 an "industrial university"; with a purpose founded on close links not just to established industries, but to developing ones.

Abertay found political and financial backing to establish the new department, offering the first computer games degree in the world in 1997. There are now a clutch of related degrees, including games design and production management, and an intriguing BSc course called ethical hacking.

Hundreds of games graduates are turned out by Abertay every year, including David Jones, founder of DMA. After Lemmings in 1991 it released the first edition of the controversial game Grand Theft Auto in 1997. It sold in the millions, and new versions continue to top the games ratings.

Trained games makers are in demand in the games industry worldwide. But like David Jones and Chris van der Kuyl a significant number of them stay on in the area, creating games and building new companies with teams they met while studying.

Vibrant industry

Like the movie business, the games industry is project-driven: you're as good as your last game (or your next one). A game may take a team a year or 15 months to deliver, sometimes much longer if it is really elaborate or modified for many platforms.

The business model is not yet a settled one; the notable Scottish games makers have learnt how to adapt. In the early days of the industry, publishers had the power, and financed games they often bought from small games inventers.

Dundee remains so IT-savvy that you can even go there to do a degree in ethical computer hacking

But social networks and broadband now make it possible (at least in theory) for small start-up games makers to reach a global marketplace directly.

And if that is too risky, there is still plenty of work for teams to work for large games companies as part of a much bigger project. That's a good way to get revenue flowing into a start-up game business without risking months of work developing a game on spec.

Some games earn billions on release, just like a Hollywood blockbuster. Many struggle to cover their costs. But it's a vibrant new industry.

So there's the evolution of a small but significant economic cluster in Dundee: from whaling, to jute, to computers, to video games, and a bold academic decision 18 years ago.

It all began with ready access to imported raw materials. But now the raw material that powers this latest iteration of the city's fortunes is, of course... people.

Peter Day reports on business and the Scottish Referendum for In Business on BBC Radio 4 on Thursday, 11 September at 20:30 BST, repeated on Sunday, 14 September at 21:30. BBC World Service will run the programme in this weekend's Global Business on Saturday at 13:30 GMT, and Sunday at 10:30 GMT.