The North Koreans setting up businesses in the South

- Published

Chon Chol-woo is one of the most successful North Koreans in the South

Restaurateur Chon Chol-woo is a household name in South Korea.

His eponymous chain of restaurants populate the country's casinos, bus terminals, and motorway service stations.

And the 45-year-old's range of ready meals are best-sellers.

"I'm proud to say that my food products are leading their departments in home shopping. The competition has been eliminated."

Yet for all Mr Chon's success as an entrepreneur, he certainly wasn't groomed for business.

Instead, he grew up in Stalinist North Korea, where private commerce is banned.

Mr Chon, who defected in 1989, is one of 27,000 North Korean escapees living in South Korea today.

Many other ex-pats from the North are following his example and trying to set up their own businesses.

Yet often they are not doing so for positive reasons - for many it is because they struggle to find employment in South Korea, or feel they face discrimination in the workplace.

And the majority of firms set up by North Koreans struggle.

'Less educated'

South Korea is a by-word for successful capitalist enterprise, led by conglomerates such as Samsung, Hyundai and LG, which grew out of the ashes of the Korean War.

The country's society is now highly competitive, and South Korean parents hot-house their kids to compete for places at the top universities and companies, where sophisticated IT skills and foreign languages come as standard.

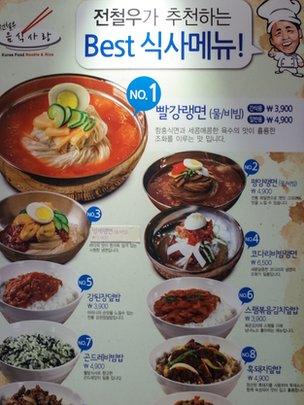

Chon Chol-woo's restaurants are a common sight across South Korea

In this environment, the lack of skills and experience of North Korean defectors is striking, and makes it difficult for them to compete.

The unemployment rate for North Korean ex-pats is more than three times that for South Koreans, and defectors last an average of 19 months in a job, compared to 67 months for their southern counterparts, statistics show.

Hwang Ye-Bin is a director of entrepreneurship assistance at the North Korean Refugees Foundation, an organisation funded by the South Korean government, which helps people from the North settle in the South.

She advises North Koreans who want to start a business, and says that most who approach her for help are those who have struggled to find any work in South Korea.

"They tend to be less educated and more elderly," she says. "And they're often not qualified to start a business. It's very rare for a venture to succeed."

Ms Hwang adds that the North Koreans also struggle to raise the funds to start a business, and lack the same support networks or institutional awareness of South Koreans.

"A bit of institutional discrimination is also inevitable - especially as many applicants are over 40, and the language they use marks them out as North Korean," she says.

'Can't give up'

Mr Chon puts his success down to hard work, but it wasn't all plain sailing.

In 2000, he lost his first restaurant business and savings to a con artist, to whom he had given a senior role.

Mr Chon bounced back, and rebuilt his empire bigger than before. "Having done it once, I knew I could do it again," he says.

Kim Sung-il is not a man who gives up on his business dreams

However, no-one perhaps knows the problems faced by a North Korean trying to start a business in the South better than Kim Sung-il.

After serving as an officer in North Korea's army, Mr Kim escaped in 2001.

Chon Chol-woo's restaurants offer Korean cuisine

Since then, he has opened - and closed - five businesses in the South: a noodle restaurant, a dumpling restaurant, a mushroom farm, an acorn-jelly restaurant and a dumpling factory.

He is now about to open his sixth venture: a poultry processing plant for Korea's famous chicken-ginseng soup.

"Starting a business was harder than I expected," he says.

"The main difficulty is not knowing many trustworthy people - we don't have connections here.

"But there are also differences in language, culture and food, so it's a learning curve."

Mr Kim has found it hard to sustain any business for longer than six months, and it's usually a lack of money that brings them down.

But, he says, working as an employee in South Korea isn't an option.

"There's almost nothing I haven't tried - construction worker, manual labourer, deliveryman, bus driver," he says.

"But it was very hard to communicate because of the differences in language and culture. I felt I was discriminated against because I was North Korean."

After all his years of trial and error, Mr Kim has high hopes for the chicken processing business he's about to open - despite not having all the funding he needs.

"I can't give up now," he says.

'Business mentality'

While older North Korean defectors such as Chon Chol-woo and Kim Sung-il came to South Korea with little knowledge of private enterprise, the experience of young men and women today in North Korea is very different.

The old North Korean system that Mr Chon and Mr Kim grew up in - with the state providing everything - has long since broken down, and new shoots of private commerce and self-reliance are starting to take root - in markets and in attitudes.

Despite photo opportunity shows of strength, the North Korean government has less grip on its economy

Therefore younger North Korean escapees are often much more business savvy.

"The younger generation [in the North] are practically South Korean," says Mr Chon, who now employs more than 100 people.

His latest project is a chain of low-cost restaurants which he hopes to export abroad.

"It's inspired by McDonalds," he says. "All the food is pre-packaged, so I don't need to pay chefs or service-staff.

"It's a concept you can replicate easily even overseas; you don't need expertise in Korean food. It's a new kind of concept for Korea.

"Even when I'm off duty, I'm always trying to find new solutions. It's about having the business mentality, just like it is for South Koreans."