Does job success depend on data rather than your CV?

- Published

The bald truth is that most companies are pretty bad at recruitment.

Nearly half of new recruits turn out to be duds within 18 months, according to one study, external, while two-thirds of hiring managers admit they've often chosen the wrong people.

And the main reason for failure is not because applicants didn't have the requisite skills, but because their personalities clashed with the company's culture.

So these days employers are resorting to big data analytics and other new methods to help make the fraught process of hiring and firing more scientific and effective.

For job hunters, this means success is now as much to do with your online data trail as your finely crafted CV.

Game for a job?

While the internet has certainly made it easier to match jobseekers with vacancies, a number of firms are moving beyond automatic keyword matching to find "suitable" candidates and trying more sophisticated analyses instead.

For example, recruitment technology firm Electronic Insight doesn't even bother to look at your skills and experience when analysing CVs on behalf of clients.

Recruiters claim that games reveal more about a candidate than a traditional CV and covering letter

"We just look at what people write and how they structure their sentences," says Marc Mapes, the firm's chief innovation officer.

Its algorithm analyses language patterns to reveal a candidate's personality and attitude, and then compares this against the cultural profile of the company.

"About 84% of people who get fired do so because of lack of cultural fit, not because of lack of skills," he maintains.

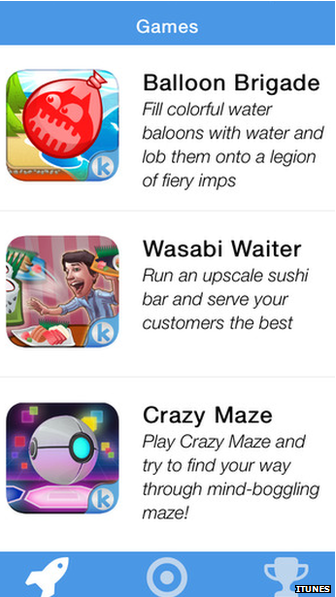

And companies such as Silicon Valley start-up Knack are even developing games as a way of assessing the suitability of job candidates.

While applicants play an online game designed to reveal their personality, emotional maturity and problem-solving skills, hundreds of pieces of information are being collected in the background and analysed by data scientists.

For example, one game, Wasabi Waiter, involves the player serving customers in a restaurant and assessing their moods and desires. Every decision and choice the player makes tells a story, often unconsciously. Play reveals our true personality, the company argues.

"Gamification is definitely coming in," says Paul Finch, managing director of Konetic, an online recruitment technology company. "Games can tell if you're a risk taker or innovator and they appeal to youngsters' gaming culture."

Size matters

But innovative personality tests are supplements to, not replacements for, big data analytics, many recruiters believe.

Analysis of historic data from tens of millions of job applicants, successful or otherwise, is helping employers predict which new candidates are likely to be the best based on a comparison with the career paths, personalities and qualifications of previously successful employees.

"Now we're able to use our own data to track how long candidates stay in a role before seeking new opportunities," says Geoff Smith, managing director of recruitment consultancy Experis.

"We can also map out and predict typical career paths based on other candidates' career histories, which makes us more efficient and more able to help candidates with their future career ambitions," he says.

Ben Hutt, chief executive of Talent Party, a UK and Australian job site aiming to become "the Google of job search", agrees that data science is saving recruiters a lot of time and money.

"We have 10 million candidate CVs on our database," he says. "Using automated semantic analysis we can match suitable candidates to relevant jobs quickly and efficiently, saving human resources managers a lot of time."

And Juan Urdiales, co-founder of recruitment website Jobandtalent, says machine learning algorithms are making the process of matching suitable candidates to relevant jobs much more accurate.

"We analyse more than 2.5 million profiles and more than 2.5 million job offers every month and learn which jobs the applicants click on and which they reject, refining the search process based on that data," he says.

Selection bias

All this data analytics is also challenging perceptions about what skills and experiences candidates should have for the post.

President Obama's White House has endorsed Evolv's software as a way of fighting recruitment prejudices

For example, San Francisco-based company Evolv found that long-term unemployed people perform no worse than those who have had more regular work.

It also found that prior work experience and even education are not necessarily indicators of good performance in some roles.

And for some reason, service industry workers who regularly use five social media platforms or more per week tend to be more productive but less loyal than their less digitally social colleagues.

Social profile

In addition to all the historic data analysts have at their disposal, social media is offering recruiters a rich new vein of real-time data.

Our blogs, websites, Twitter rants and LinkedIn profiles reveal as much - if not more - about us than a semi-fictionalised CV.

"The days of keeping your personal and professional profiles separate are over," warns Experis's Geoff Smith.

"Social media is a great platform for individuals to demonstrate their expertise, experience and enthusiasm for their field of specialism. However, candidates need to be conscious of the online reputation they are building and the data trail they are leaving behind."

A growing number of tech companies are offering tools that can sift through masses of social media data and spot patterns of behaviour and sentiment.

Employers are watching: what does your social media profile say about you?

"Online tools, such as Sprout Social and Hootsuite enable our recruiters to keep an ear to the ground on what's going on with their clients, candidates and in the sectors we're working in," says Mr Smith.

Konetic's Paul Finch agrees that applicants need to be aware what image their online profiles project.

"It's all about reputation. If people can't manage their own reputations, how are they going to protect the reputations of their future employers?" he asks.

Human touch

But technology can only take us so far, argues Jerry Collier, director of global innovation at Alexander Mann Solutions, a company sourcing staff for blue-chip companies including HSBC, Rolls-Royce and Vodafone.

"Recruiting should be about relationships," he says. "Technology is only there to make that process simpler and more efficient.

"If you want diversity and a richer, more creative workplace, you need people from different backgrounds and experiences.

"Leave that to an algorithm and it will probably come up with the same type of person every time."

Talent Party's Ben Hutt agrees, saying: "When you apply data science to 10 million CVs, it becomes something really useful.

"But data science is never going to replace the face-to-face interview."