Celtic kitten: Ireland's tech start-ups flex their claws, ready to play

- Published

Celtic kitten: Are Ireland's tech start-ups ready to flex their claws and play with the big boys?

Dublin City Council now has a commissioner for start-ups, external - Niamh Bushnell, a veteran of new technology-related venture battles in both the Republic of Ireland and New York.

"Everything I'm seeing is on a par, in terms of companies, talents and innovative ideas, with what I know best - which is the New York tech scene," says the new commissioner.

It's all part of a new dotcom boom in Ireland, which has boasted success stories like peer-to-peer currency market CurrencyFair and payments provider Realex Payments.

While the Irish domestic financial sector has dwindled since the 2008 downturn, internationally-trading financial technology (fintech) companies have trundled on, gaining customers abroad to replace falling domestic demand.

Fintech "stayed ahead of the curve, and performed during the crisis, even though it was a financial crisis in its nature", says leading Irish economist Dr Constantin Gurdgiev.

Niamh Bushnell is the new start-up commissioner for Dublin City Council

Now the Irish Republic is in the midst of an economic recovery, with surprisingly strong second-quarter data leading Finance Minister Michael Noonan to predict 4.5% economic growth this year.

And if the Irish economy is finally healthy after six years of painful austerity, the information and communications services sector is frenetic.

Growing 9.9% year-on-year in the three months through July 2014, the tech sector is buoyed by a low corporate tax rate, use of the English language, and high levels of tertiary education after the Tiger years.

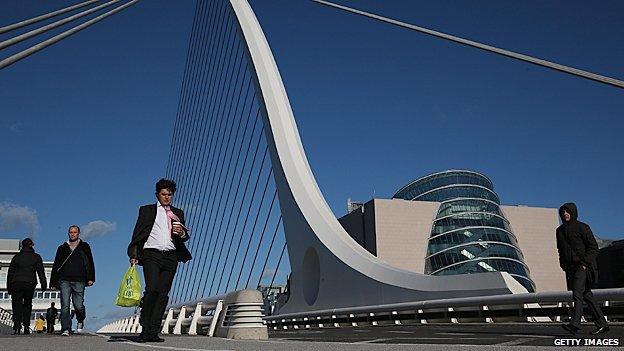

Raise a glass: After a painful downturn, the Irish economy is finally looking healthier

Peer to Peer

"I'm actually Australian," says Brett Meyers, co-founder and chief executive of CurrencyFair, now a poster-boy for successful Irish tech entrepreneurs.

The company is the world's largest peer-to-peer currency exchange, operating from the south Dublin neighbourhood of Ranelagh.

CurrencyFair chief executive Brett Meyers shows Irish Taoiseach Enda Kenny how the site works

CurrencyFair, based in south Dublin, is the world's largest peer-to-peer currency exchange

Being an expat himself, Mr Meyers quickly became aware of bank premiums in sending money internationally, and decided to launch a person-to-person market on the model of betting site Betfair.

"You choose your odds - choose your own exchange rate, and if someone else decides it's a good rate, the two of you do a deal," he says.

Mr Meyers initially looked to the UK as a possible home, but ultimately chose Ireland because of support offered from Enterprise Ireland - a government body begun in the Tiger years to foster homegrown companies with potential to create employment or exports.

The company is expanding quickly.

"We're processing on average about 5m euros (£3.9m; $6.4m) a day - and we're growing in multiples each year, so not long till that's 100m euros a day.

"That's growing massively, but it's a lean and efficient model, so our staff will grow, but nowhere near as fast as our transactions will grow."

Ben Hurley is chief executive of the National Digital Research Centre (NDRC), an early-stage investor set up by five Irish universities to incubate new start-ups.

"We've been investing for six years now," he says, with 150 ventures passing through their programme, 60% finding success at the next, seed capital, stage.

"It's not just about the craic and vibrance," he says. "These are companies with significant amounts of market cap."

Ben Hurley is chief executive of NDRC, the National Digital Research Centre

NDRC was set up by five Irish universities to help start-ups

Wired yet for success?

Colm Lyon is another Dublin tech entrepreneur, who in 2000 founded Realex Payments, which processes 28bn euros a year in payments for clients like Aer Lingus, Paddy Power and Virgin Atlantic.

Realex's Colm Lyon says Ireland has a way to go in encouraging entrepreneurship

Growing by a third in each of the last three years, his company is in the process of scaling up dramatically, with HSBC and Santander bundling Realex's services to their own clients. The company recently received a British payment institutions licence, allowing it to compete with bank current accounts.

"We give our customers accounts in the different clearing systems directly," he says, speeding payments between the euro and sterling areas.

"On the start-up scene there is a great buzz around Dublin now, with numerous incubation programmes and seed capital more available."

Nonetheless, Mr Lyon thinks Ireland has some way to go to foster entrepreneurship as much as its neighbour.

Since 2009, when the Payment Services Directive, external was enacted, Ireland has licensed 12 institutions, compared with over 1,300 by the UK.

He points to effective British schemes for investing in start-ups, and high Irish capital gains tax of 33%, compared with the UK's tax relief of 10% on the first £10m for entrepreneurs.

Despite the downturn, Ireland's fintech start-ups flourished as they were not reliant on the domestic market

"We still treat an entrepreneurial game the same way we do a speculative game - if you set up a business, you get taxed the same way as if you bought three houses. They're different, and I think should be treated differently," says Mr Lyon.

Stripe - a thriving PayPal rival, which moved to the US after not receiving funding from Enterprise Ireland - is an example of what can happen.

Ian Lucey, an investor specialising in the technology sector, says Ireland has ample government funding through the first €100,000 to €200,000 of investment, "but... there isn't a huge angel network in Ireland yet.

"Start-ups are managing to raise the first bit, but the challenge is the next half million."

This is also why, he says, Ireland has excelled at business-to-business software, but less so at business-to-consumer applications, which are pricier.

Shared e-ecosystem

On the flip side, much Irish tech-sector activity - it is difficult to say from current statistics, but Dr Gurdgiev estimates four-fifths - comes from multinational titans like Google, Amazon and Yahoo, which have located offices in Ireland to take advantage of its low corporate tax rate, a process economists politely call 'tax optimisation'.

How does it affect young minnows to exist in the shadow of lumbering giants of the internet?

Ms Bushnell believes the relationship is symbiotic.

"I worked for large multinationals in Dublin, and then went to do my own thing as an entrepreneur," she says.

Modern Dublin is European home to some of the world's technology giants, but is this a barrier for start-ups?

"People who are entrepreneurial are not going to change their spirit because there are multinationals in Dublin. If you have the fire in your belly, that's not going to go away."

But Dr Gurdgiev is more sceptical - cost competition, he says, makes it difficult for start-ups to recruit talent, or preserve it from being poached.

"Ireland is suffering from a resource curse. You have multinationals sucking any talent on the technical side, willing to pay them an extra premium in wages, because part of the return from employing them is distorted by tax optimisation."

At any rate, says Mr Hurley, "there's only so long you can be a FDI [foreign direct investment] junkie."