Ecommerce: Tabaski rams bought in Paris, eaten in Dakar

- Published

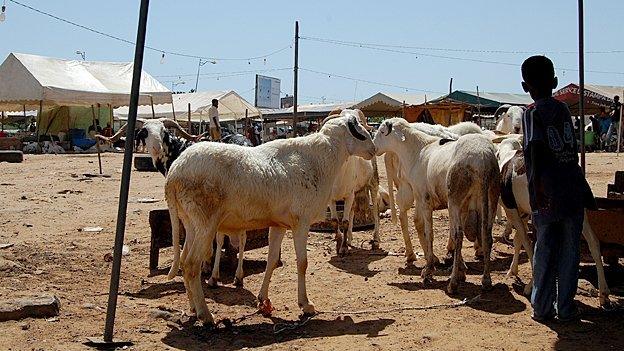

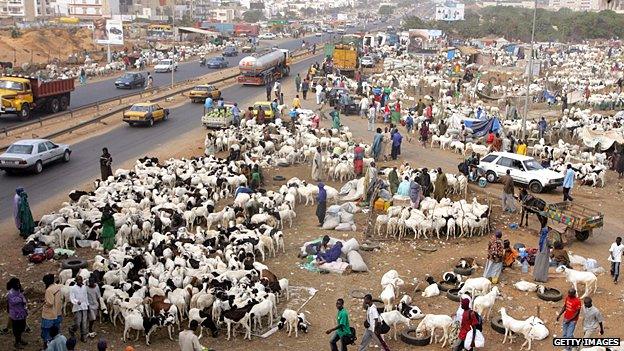

Counting sheep: Across Senegal's capital, Dakar, rams crowd streets and parks destined to be sacrificed for Tabaski

"It's a party, it's joy, you know. We go to mosque in beautiful new clothes, the women prepare the sauce, the meat, we eat together at home and with our neighbours. It's really marvellous."

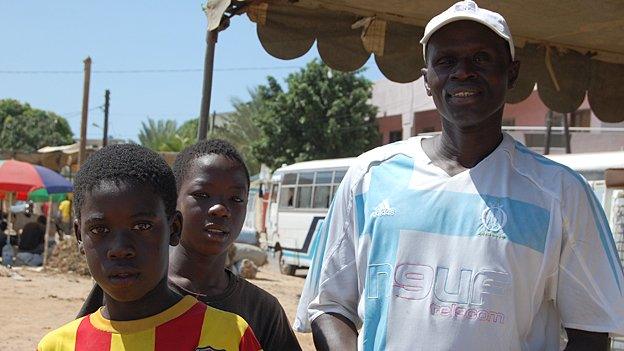

Abdulaziz Nder sells sheep. More particularly, once a year he takes sheep into the centre of Dakar, a vibrant, sun-drenched city of eight million inhabitants, where he will spend several weeks selling his animals.

"Each Senegalese, each Muslim, must do everything he can to have a ram, because it's a command from God," he says, standing in the middle of a dusty town square overflowing with fine ovine specimens trying to find shelter from the midday sun.

This is Tabaski - known elsewhere as Eid al-Adha - the biggest festival and holiday of the year in Senegal, a country that is 90% Muslim. This year it falls on 4 October.

It's a time when families travel great distances to come together and share a meal.

Also travelling great distances are the sheep bound for the dinner table.

Border controls are relaxed and customs fees waived, as hundreds of thousands of sheep pour across the borders from neighbouring countries such as Mali and Mauritania.

Abdulaziz Nder: The quality of the meat is better when they are young. But for some it is more important that they are bigger. It depends on taste.

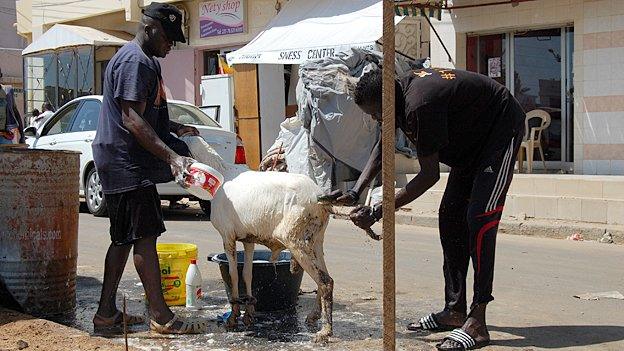

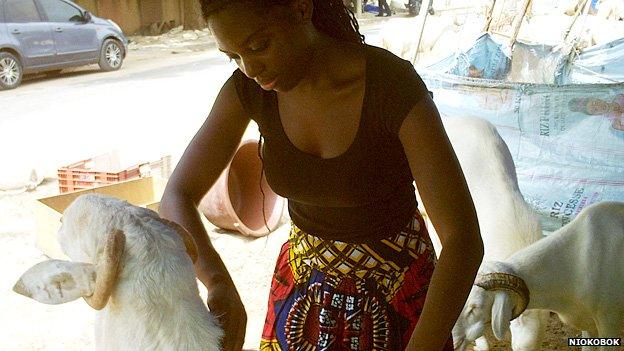

Each ram is given a thorough toilette, so they look their best for prospective buyers

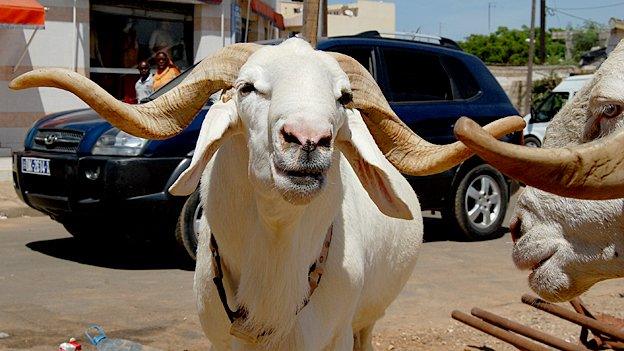

The acquisition of a healthy ram is a source of great pride to a family - and size matters. Across the city on closely guarded rooftops, in yards, and even in apartments sheep are being fattened up.

There are always concerns about supply - this year, the government says there should be enough, external. There's even a hugely popular annual televised, external beauty contest called Khar Bii, external - "this sheep" in Wolof.

The animal is ritually slaughtered at dawn and then cooked and eaten, with plenty to share with friends and neighbours, both Muslim and Christian.

In one day nearly 800,000 sheep and goats will be killed - with 250,000 needed for the capital alone.

Families save all year to be able to buy a ram - if that is too expensive a goat will do, but no-one likes their neighbours to think they haven't been able to provide for the family

For several weeks central Dakar is transformed into a giant sheep ranch - these melancholy animals cluster on pavements, in front of offices, in parks, on the beach

The population of Senegal is sitting around the 14 million mark - of whom 4 million live in the capital, Dakar

Over the sea

Which makes it a difficult time of year for those living far from home.

An estimated $1.3bn was sent back, external to support loved ones by almost half a million Senegalese working overseas in 2010.

Sending money home can be very expensive, and there's always the danger that the cash isn't spent on what it was intended for.

Short-lived friendship: The biggest, fattest rams can cost hundreds of euros, while the slightly smaller and cheaper animals sell out fast

Which is where an ecommerce start-up called Niokobok comes in.

The company lets the Senegalese diaspora around the world shop online for food, electronics and solar systems sourced in Senegal to be delivered to family and friends there.

They also deliver rams and goats for Tabaski - as well as all the traditional trimmings: potatoes, onions, and sauces. Customers can go to the website and view videos of the animals for sale, before making their selection.

Niokobok's customers can choose their sheep by watching a short youtube video

Mme Ndiaye lives in Guediawaye, a suburb of Dakar, sharing a tiny courtyard with children and grandchildren. Her son has groceries delivered once a month.

"When I receive the delivery it is as if he is here in Senegal, and he is delivering it himself," she says. Her son has lived in France for so long now that she has lost count of the years.

"If you have a son who loves you and helps you like this, he is never far away."

Electric sheep: Niokobok's Olivia Douglas prepares a ram for delivery

Advert for Tabaski sheep in one of Dakar's high end shopping malls - the festival is impossible to ignore

Last year, he sent her two animals, so the family could celebrate in style.

"Before he would send money, and my son or daughter would then have to go to the shops. It is better to get the delivery," she says.

"I thank God and the prophet Mohammed for the deliveries. I'm so grateful to my son, because he's taking care of me."

Now in its second year, the company delivers to around 1,000 families.

Initially, the team behind Niokobok thought that the main draw would be that customers would know where their money was going.

"This is still true," says chief executive Laurent Liautaud.

"But we also see it's that people thinking about their relatives, and wanting to make them happy, so they want to send a gift."

"What's very interesting is that we see demand from the Senegalese living in Senegal, because online retail is only beginning here."

Laurent Liautaud (second left) with the Niokobok team

Niokobok's product line is all sourced in Senegal

Niokobok isn't the only African ecommerce company concentrating on the diaspora.

Kenya-based Mama Mike's, external was an early entry, with recent addition African ecommerce giant Jumia announcing a UK-based site in June, external aimed at expat Nigerians.

But online shopping is still finding its feet in French-speaking Africa, giving Niokobok an early lead.

The team of five are based at the CTIC incubator in the heart of the city, and are working with the United States Agency for International Development (USAid) as part of their Development Innovation Ventures programme on expanding to rural areas.

"We're really trying to improve the life of our customers," he says, also pointing to the solar systems available on the site.

"[Solar] for people from the diaspora is great, because you're based in Paris, and you want to send light to your family, you can do it, thanks to the internet," says Mr Liautaud.

"We [still] believe food is important, it's more than 45% of customer spend, so even if it's a logistics nightmare, we need to market food."

And the logistics are not to be sneezed at.

"You have much less reliable partners, so you have to do a lot of your logistics in-house, even from the beginning which is costly. On food especially you have quite low margins, so it's more difficult to recover your costs," he says.

Early in the morning, Dakar beaches come alive with people washing their sheep in the sea

"The only good thing is that consumption patterns are much more standardised."

Home delivery in countries where the transport infrastructure may be lacking, and mapping isn't accurate presents a challenge. Then there's the lack of standardised addresses - making local knowledge vital.

"A lot of our customers put things that help, like this is next to this school, or this very famous point of the neighbourhood. Often for the first delivery we do the last 200m on the phone," says Mr Liautaud.

Niokobok has plans to roll out to the whole of Senegal before trying neighbouring markets.

This year's livestock delivery is keeping the team busy in the meantime, with close to 50 orders to fulfil. With each delivery a picture is taken to send to the buyer, strengthening that connection to distant family.

"For Islam, it is very important for the family, because on the day of the judgment, every head of the family will ride on those sheep to go to paradise," says Niokobok's Moussa Diallo.

"It is why people choose to buy very big or very fat sheep."

These sheep need no passports to cross borders - it's a Tabaski free for all