Portugal's health tech start-ups go the long way round

- Published

Tortoise and hare: Slow but steady will win the race when it comes to healthcare technology

When Joao Fonseca took his three-year-old son to the doctor, he was upset that he had to wait a few days for the results of a blood test.

As a university researcher in the field of biophysics, he decided to try to turn the problem into a business.

That was in 2005.

Nine years and €12m ($15.2m; £9.4m) later, Mr Fonseca recently started selling a portable device capable of conducting common blood tests, giving the results in minutes, anywhere that it can be plugged in.

Biosurfit is a Lisbon-based biotechnology company that employs 63 people. The device is called Spinit, and vaguely resembles an old computer from the 1980s.

Healthcare professionals take a drop of the patient's blood and put it on a disc very similar to a DVD.

Health tech start-ups face a long wait to be able to take their product to market

"I didn't invent the concept of lab on a disc," acknowledges Mr Fonseca. There are other portable devices able to do blood tests.

The goal, he explains, is to have a device able to do up to 30 different tests using very cheap discs.

Discs are manufactured in Lisbon, and the company is aiming to bring production costs down to €1 per unit. Each test requires a different disc.

Biosurfit has obtained regulatory approval to market two of them in Europe, and they expect to launch another two in the next 12 months.

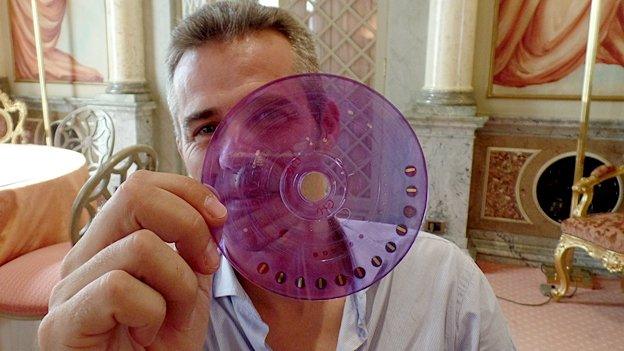

Joao Fonseca with one of the discs used in his portable blood testing machine

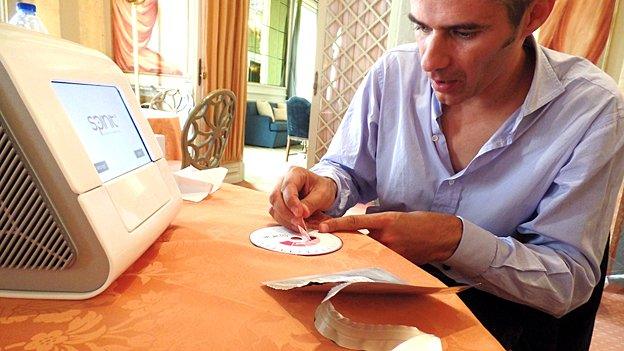

The Spinit portable blood testing device. Each disc tests for something different

Slow development

It's been a much slower journey than Mr Fonseca expected.

"I thought I could develop the technology, take the product to market and break even in four years." Instead, he says, it has been "a long distance race".

Launching a business in biotechnology takes a lot of time.

"The sector has long development cycles because that development is based on science," explains Nuno Arantes-Oliveira, president of P-Bio, Portugal's Biotechnology Industry Organisation.

Carlos Faro, a university professor and founder of Biocant, an incubator for biotechnology start-ups, agrees. "This sector is very demanding in terms of investment and has a long-term return. A company needs dozens of millions of euros."

Another challenge, says Carlos Faro, is mentality.

"Most of these entrepreneurs come from an academic background. They have to stop thinking like scientists and start thinking like a business person."

Kinematix makes motion sensor based devices for use in the healthcare industry

Kinematix, another Portuguese health technology company, has raised around €5m in venture capital since its inception in 2007.

The company, based in Oporto, employs 24 people, and builds motion sensor devices with a variety of healthcare uses. They started selling them earlier this year, and are now looking for new funding to expand.

One product is an insole connected to a small gadget, that tracks where users apply pressure while walking.

It was designed to help doctors treat patients with diabetic foot, a condition that causes foot ulcers that should not be pressed while walking.

A similar Kinematix technology is used to monitor prostheses usage and to make necessary adjustments. It could also be used to garner information about how athletes walk and run, and to help prevent injuries, says company founder Paulo Santos.

Mr Santos's plan is not to make money by selling the devices. Instead, he charges healthcare professionals access to online reports about each patient.

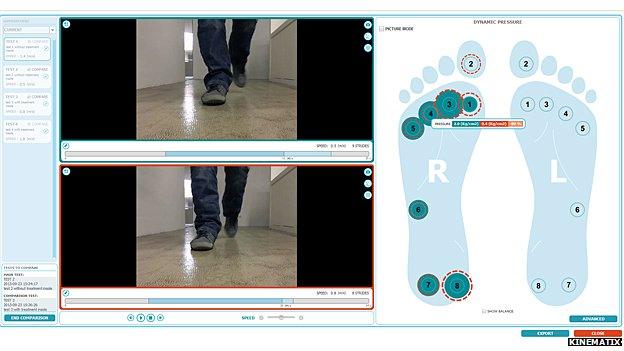

The Walkinsense measures how patients walk - otherwise known as gait analysis

It is used to design footwear for patients with diabetic foot, with gait issues and other orthopaedic problems

Regulatory challenges

Kinematix has clients in the UK and the Netherlands, and they're trying to extend operations to the US, where they have been granted regulatory permission to enter the market.

This regulation is a double-edged sword for investors, says Mr Arantes-Oliveira, from P-Bio.

"There's a development risk, a regulatory risk, but less of a market risk," he says.

This happens, he argues, because while it may take time to start selling a new product, a regulatory approval certifies its quality and innovation.

Different markets also require different approval processes, and this is a field where companies typically need to sell in several countries, notes Mr Arantes-Oliveira.

"These companies are born global. Many of the entrepreneurs had international experience before."

Joao Pereira founded Magnomics along with four other researchers after completing his PhD in Cambridge.

The company is just starting to develop a portable device to detect different types of bacteria on samples such as blood and saliva.

The Magnomics team has decided to start with applications for their device involving animals, as the cost of entry is lower

The aim is to let doctors prescribe targeted antibiotics more easily.

They've raised €600,000 from private investors and from a government-backed venture fund called Portugal Ventures, who also invested in Kinematix and Biosurfit.

The goal is to have a working prototype before the end of next year.

Magnomics initially wanted to enter the human health market, but they decided instead to start with the veterinary market, where regulatory barriers are lower and companies don't need as much investment to have a product ready.

"We were asking for too much money, because that's what it takes to enter human health," says Mr Pereira.

Now, they plan to start with the bovine market. "It's not the sexiest of pitches," Mr Pereira admits. "But it is also not the kind of girl everyone wants to go out with. It's a market in great need for innovation."