Doing business the Chinese way

- Published

The mystery of China's "guanxi" explained

When Chinese entrepreneurs Deng Feng and Michael Yu took a BMW out for a test drive together, they managed to get into an accident and completely destroy the car.

As soon as they stepped out of the wreckage, Mr Yu told Mr Deng not to worry, as he would take care of it.

"So I know what kind of person he is. Through those kinds of intimate scenarios we can definitely know each other very well," says Mr Deng.

Mr Yu is chairman of the New Oriental Group, one of China's biggest educational service businesses, and Mr Deng is chair of Northern Light Venture Capital, a Chinese venture capital firm.

Both are members of the exclusive China Entrepreneur Club (CEC), a not-for-profit group of 46 of China's top entrepreneurs and business leaders.

Already good friends from their membership of the club, which includes trips to each other's workplaces, nights out and annual trips abroad together, their experience that day was a classic example of having so-called good "guanxi".

Roughly translated as "relationships" or "connections", it is a crucial part of life in China.

Having good "guanxi" - a wide network of mutually beneficial relationships developed outside the formal work setting, for instance at evening meals or over drinks - is often the secret to securing a business deal.

Mr Yu, who is on the board of the CEC, says it is because of this that the number of CEC members is limited. The small group size ensures people can really get to know one another, build close connections and ultimately help each other out.

Getting to know people outside the formal work setting is crucial in China

"We have had a lot of occasions for example, when members are in trouble or got into difficulty the entire club is behind a person, or we divert a lot of time to help that particular member through a difficult time," says fellow CEC member Charles Chao, the chairman and chief executive of online media firm Sina Corporation.

The favours are reciprocal - if a person helps somebody out, he or she will expect to be repaid at some point.

To those in the West, where you can secure a deal through formal meetings even if you don't know someone, this "you scratch my back and I'll scratch yours" way of doing business can seem improper.

Yet views that it is a negative activity, often linked to corruption, are misplaced, says Mr Deng, who emphasises that guanxi is a "neutral" word.

Guanxi is only corrupt if the activity is illegal, for example, paying a bribe

He points out that the Chinese generally tend to be less private and socialise more with their colleagues than their Western counterparts, and doing deals this way is a natural extension of that.

While guanxi is obviously open to abuse, it is only corrupt if the activity performed as part of the relationship is illegal, for example, paying a bribe.

Leadership expert Steve Tappin says it's simply part of the "social fabric" in China. "It's very difficult to get things done without it," he adds.

In fact most business leaders say it's downright impossible.

"Right now in China, no matter how strong or how smart an entrepreneur is, as long as he does not belong to the business community, does not have a lot of friends who may help him, he's not gonna win for long," says Joe Baolin Zhou, chief executive of Bond Education Group, the largest private education service company in southern China.

This seems fundamentally unfair, surely if a product or service is good enough it should succeed on its own merits?

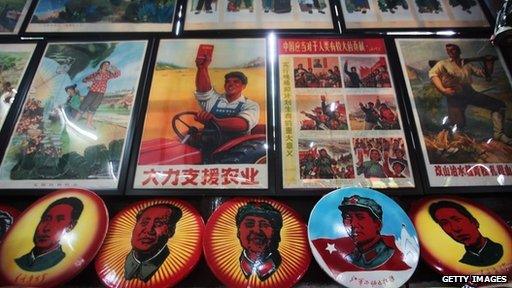

Guanxi became an important way to rebuild trust after the Cultural Revolution

Yet guanxi's roots are tightly bound in history, with the notions of obligation and loyalty going back thousands of years.

The Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, when families and friends were encouraged to report on one another in a bid to enforce communism, meant that guanxi's importance increased as a way to rebuild trust, says Kent Deng, associate professor at the London School of Economics.

And he points out that when China first started to encourage development of a market economy there was no proper network or written contracts so doing business with a known network was initially the only way to ensure that they wouldn't be taken advantage of.

Yet slowly that way of doing business is changing as Chinese firms become more globally focused.

Eric Yang chose an internet business because it offered a new way of doing things

Eric Yang is co-founder and chief executive of online education platform TutorGroup.

He says he chose an internet-based business precisely because it offered a new way of doing things.

Longer term, he says, this type of company offers much greater growth prospects than the traditional way of doing business, as it offers the potential to reach a much greater audience, beyond personal connections.

"That's the beauty of the internet, you get contact with so many people but you don't need to know their name. But you can still sell the product to them, give the service to them," he says.

This feature is based on interviews by leadership expert Steve Tappin for the BBC's CEO Guru series, produced by Neil Koenig.

- Published22 September 2015