Has Royal Mail reason to celebrate its 'first' birthday?

- Published

For 30 years politicians toyed with the idea of privatising Royal Mail. This time last year the government finally managed it.

But 12 months on from Royal Mail's flotation on the London stock market, questions over the rights and wrongs have not gone away.

What's more, instead of resolving issues over Royal Mail's future, the sale has underlined the company's challenges - most notably from competitors such as TNT, UPS and UK Mail.

Yet, for Shore Capital analyst Robin Speakman, the flotation must go down as a success. Remember the climate, he says: political angst, union sabre-rattling, problems in the financial markets.

And now? "The business is stable, the share price still trades at a premium, industrial relations is not an issue, the business is generating cash and has paid its first dividend."

There are problems ahead, he says, "but the first year has been an achievement."

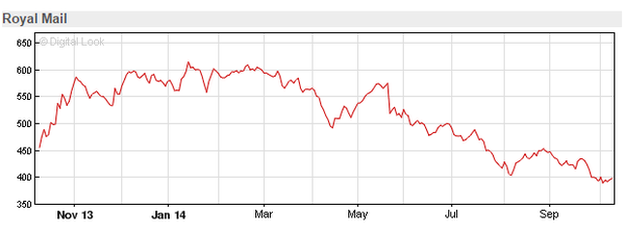

A lot of people made a lot of money - especially professional investors - if they sold their shares in the early months after the flotation.

There's less money to be made now, however.

The shares were priced at 330p and surged by more than a third to 455p on their first day, eventually reaching a high of 616p in January.

But at the end of September, Royal Mail shares fell below 400p for the first time since they started trading.

Toe in the water

Michael Hewson, chief market analyst at CMC Markets, says that after a rollercoaster few months the share price is now settling at a sensible level that reflects Royal Mail's trading prospects.

CWU leader Billy Hayes says there is still shopfloor "discontent"

"Much as I hate to defend politicians, and particularly [Business Secretary] Vince Cable, he was right in saying that there was an awful lot of froth in the share price in the months after the initial public offering," Mr Hewson says.

But he feels that the "euphoria" around the float had an important by-product - bringing small investors back into the market after getting their fingers burned during the global financial meltdown.

"It re-invigorated private sector involvement in the stock market. People were dipping their toes back in the water. And that is a good, healthy thing for a properly functioning market," Mr Hewson says. "The culture of investing had been seriously damaged by the events of 2007 and 2008."

However, despite the share price fall, the union leaders who opposed the sell-off have seen nothing since to dissuade them that the taxpayer was short-changed.

For Billy Hayes, general secretary of the Communication Workers Union (CWU), the falling share price is irrelevant. He says: "After the sale, the price soared. Vince Cable could have got more for the taxpayer.

"The flotation was a disaster. The fact is, it was over-subscribed, and notwithstanding the recent fall in the share price, Cable lost £1bn on the way to the stock market."

Royal Mail in numbers

Revenue: £9.1bn

Operating profit: £671m

Employees: 150,000

UK deliveries: 14bn letters; 1bn parcels

Collections: 205,000 across UK, using fleet of 40,000 vehicles

Mr Hayes points to the subsequent post-mortem into the sale process, and into how future governments handle privatisations. "Cable cannot say that the privatisation was good - and then hold an inquiry into it."

'Flipping'

Mr Hayes and Mr Hewson may come from different ends of the corporate spectrum. But they agree that the role played by some key institutional investors discredited the flotation process.

Core investors were allocated shares on the understanding that there would be no immediate profit-taking, or "flipping". It didn't turn out that way.

"The flipping didn't look good," says Mr Hewson. "Not locking in these investors was not the wisest thing to do." But it cannot alone be blamed for the initial surge in the share price, he says.

Royal Mail's sale was at a time when some investors were awash with cash. With interest rates low and good returns on assets hard to find, there was plenty of money looking for a home.

"Royal Mail was a victim of this," Mr Hewson says. "And I don't think that politicians understood that."

The main aims of the privatisation, according to Mr Cable, were to free Royal Mail to become a commercial entity while also meeting its legal duty to provide the Universal Service Obligation (to deliver mail everywhere at a standard price).

Mr Hewson has yet to see much sign of Royal Mail's newfound competitive nimbleness, although he accepts that it is probably too early in the company's free market history. (Royal Mail did not respond to requests for an interview.)

Mr Hayes says there remains a lot of "discontent" on the shopfloor. Staff "are under pressure as the workflow changes".

But the union is still "taking stock" of the impact of the privatisation, he says. Another way of reading that is: nothing has yet happened to worsen industrial relations.

'Handcuffs'

Of more immediate concern to people is the future of the Universal Service Obligation (USO). While Royal Mail's competitors are able to cherry-pick the most profitable delivery areas - mainly big cities - the company has to provide a universal service.

Now, MPs have agreed to look into the matter.

For Mr Speakman, the USO issue must be resolved soon. "We have to decide as a country whether to abandon single pricing and the Universal Service Obligation, or put handcuffs on the competition. The politicians must make this choice."

It doesn't help that Royal Mail staff still enjoy relatively good pay and pensions, while some competitors can chip away at its market using staff on the minimum wage and zero-hours contracts.

But even if the status quo continues, most City experts are optimistic about Royal Mail's long-term prospects.

The competitive threat, poor trading over the key Christmas period, and contraction in the European business are all problems on the horizon. It is well known that the letters and parcels businesses have been under pressure for years.

Yet, as Mr Speakman points out, if it's all so bad, why are so many competitors trying to muscle into the market so aggressively?

- Published9 October 2014

- Published6 October 2014

- Published3 October 2014

- Published24 September 2014

- Published22 May 2014

- Published22 May 2014

- Published11 October 2013