Silicon Valley's billion dollar start-up failures

- Published

Burn, baby burn: Some tech start-ups are burning through cash at the same rate as a small African nation - but to what end?

The US tech start-up scene is often associated with glamour, cash and companies with astronomical valuations. Just look at the multibillion dollar flotations of Facebook and Twitter.

But according to some of the US's leading tech investors, a darker side of the dream may now be emerging.

Last month Bill Gurley, a prominent venture capitalist, and investor in billion dollar companies like Uber and OpenTable, warned that start-ups were "burning" (read losing) huge amounts of cash, external in a bid to build their businesses.

In fact, in an interview with the Wall Street Journal, external, he said the levels of risk being taken on were "unprecedented" since the dotcom crash of 1999.

Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures, an investor in Twitter and Tumblr, backed him up, adding that he had "multiple portfolio companies burning multiple millions of dollars a month".

Benchmark's Bill Gurley told the Wall Street Journal: "I do think there is a high likelihood that we'll see some high-profile failures in the next year or two."

Finally, Marc Andreessen, of Andreessen Horowitz, an investor in Airbnb and Foursquare, warned: "When the market turns, and it will turn, we will find out who has been swimming without trunks on: many high burn rate companies will vaporise."

While this may all sound a bit like Silicon Valley jargon, the investors were actually saying something quite simple: the start-ups building our favourite apps and websites are spending far too much cash and may end up paying for it before too long.

The stats seem to bear out their claims.

Seattle analysts PitchBook say burn rates among all but the smallest US software companies have risen dramatically, external over the last four years, and are indeed at their highest levels since 1999.

In fact later stage start-ups - those most likely to have a significant customer base already - are splurging an average of $1.82m (£1.1m; €1.42m ) per month.

Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures says he has "multiple portfolio companies burning multiple millions of dollars a month"

Marc Andreessen: "When the market turns ... many high burn rate companies will vaporise."

Winner takes all

But what's all this cash being burnt on? And is, as Mr Andreessen claims, the market going to "turn"?

According to Bill Reichert, of early stage venture capital fund Garage Technology Ventures, what's driving the spending is the fierce and growing competition between the biggest start-ups.

Often firms like the taxi hire app Uber have little technological advantage over rivals like Lyft - so instead they end up in "pitched battles" to win market share.

"You have very much a winner takes all dynamic. There can only be one Twitter, there can only be one Facebook, there can only be one Whatsapp, even though there are other communications apps, social networks and micro blogging tools," says Mr Reichert.

"Once you're in that game you're trapped. You can't afford not to try to be the winner, and that costs a lot of money."

To gain an edge, start-ups are raising sometimes enormous sums of venture capital - note Uber's $1.2bn round in June - which they spend on marketing or attracting new staff.

Meanwhile, their venture capitalist backers have little choice but to keep bankrolling them, even though many of their portfolio companies aren't actually making a profit.

Uber is currently locked in a battle for dominance with competitor Lyft

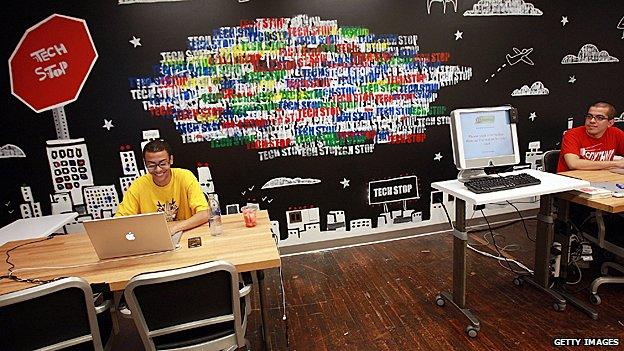

What's most galling for investors is that start-ups, newly flush with cash, often splash out on unnecessarily large office space and other perks.

Danielle Morrill, founder of California start-up MatterMark, a provider of company data, says she's "definitely seen some start-ups where the company makes no money and yet their office is ridiculously nice".

Adley Bowden of Pitchbook

"It's dangerous, because it sends a message to employees that the company has already made it when it hasn't."

Adley Bowden of PitchBook adds that often companies indulge in a bid to keep up with the Jones's.

"Some of the things that bigger companies can provide, smaller companies feel they should provide as well as a perk, but it hits your balance sheet a lot harder than it hits Google's.

"Do you want to have free lunches for all your employees or spend that cash on two more employees?"

Keeping up with the Jones's is probably not the best strategy when your competition in the office space area is the likes of Google - this is their New York Office - who have deep, deep pockets

Double bubble

With late-stage start-ups like Snapchat and Uber attracting huge valuations this summer ($10bn and $17bn respectively), some have warned a bubble may now be looming.

But there are good reasons to doubt we'll see a rerun of 1999, when the dotcom crash wiped some $5trn of stock market value from tech firms.

That is primarily because the companies Mr Gurley and others are worried about are privately held, rather than publically owned, making the risk of a macroeconomic crash unlikely. Still, when blow-ups happen they are devastating.

In 2011, solar power tech start-up Solyndra filed for bankruptcy, after burning its way through $1bn in venture capital funding. And Better Place, a start-up provider of battery stations for electric cars, shut down in 2013 after losing $850m.

Burn out: This art installation, which was exhibited in the Berkley Botanical Gardens, is made from unused tubes that were to be used by solar start-up Solyndra, before it went bust

Cut off: Electric charging start-up Better Place closed its doors in 2013

More of such meltdowns could result in layoffs and holes in investors' pockets. But the current trend could end up damaging innovation, too.

It's important to remember that a majority of start-ups will in fact fail—but venture capitalists tend to invest in multiple firms, in the hope at least few hit big and cover their losses.

However, it's arguable companies that should fail sooner are being propped up, wasting valuable investment and human resources that could be deployed elsewhere.

Hammering that home, a recent CB Insights survey found some 42% of failed start-ups blamed their demise on a basic lack of a market need, external for their product.

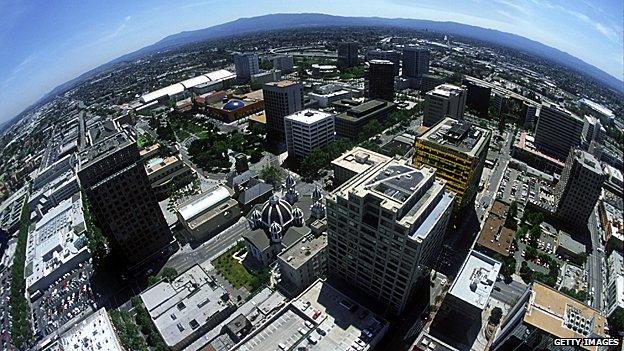

Cautionary tale: This is San Jose, in the heart of Silicon Valley, in April 2000 - just as the dot com bubble was starting to burst

If venture capitalists get their fingers seriously burnt, they may pull back from investing in the first place.

That wouldn't only mean fewer apps and services coming to market, it could hit the tech giants, who increasingly buy in new technology from start-ups, rather than create it themselves.

"There is an interesting discussion going on as to whether venture capitalists and start-ups are the new R&D portion of larger companies." says Pitchbook's Mr Bowden.

Bill Reichert is more philosophical, arguing that what is lost in start-up failures is usually "contributed back into the system in terms of talent that moves on to a higher use".

"It is absolutely not hurting the innovation economy … It gets absorbed into other products, companies and technologies."

For now, it seems start-ups are content to keep riding the wave, but concerns a correction lies ahead are mounting.

As Fred Wilson points out, "At some point you have to build a real business, generate real profits, sustain the company without the largesse of investor's capital, and start producing value the old fashioned way."

Let's see if they heed his advice.