Internet.org wants to connect India's offline millions

- Published

Most Indians access the internet through mobile phones but it can be very slow. Does Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg have the answer?

Most parents would love to get their teenagers away from computers.

But not in one poor suburb on the outskirts of Delhi, where youngsters are sent to learn.

Sharing a few laptops between them, they're being taught some basic online skills - how to search for information, how to send money to their families in the villages and how to book train tickets.

None of the children have access to computers in school. Nor do they own one.

Children of migrant workers from Bihar, they study in a government school in the neighbourhood.

Like 16-year-old Priyanka Singh, who says getting online has changed her life.

"Earlier we had to pay agents a lot of money to book our train tickets or trust strangers to carry our money back home. Now I can help my father do everything online," she says.

Priyanka Singh (middle) says being able to use the internet has changed her and her family's lives.

The students want to know how safe is internet banking? Why is the Indian railways website IRCTC.com so slow? How do they download apps from the android store?

Join the dots

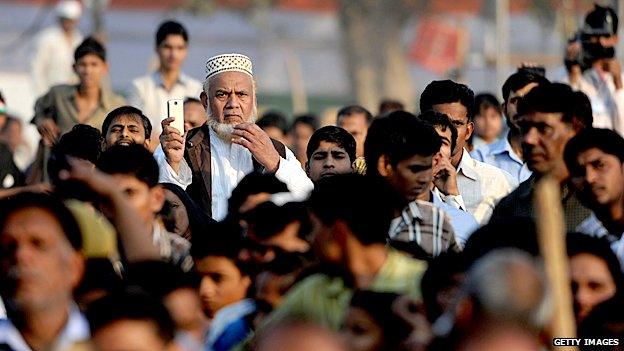

In India, more than a billion people - that's the equivalent of the populations of Europe and the US combined - are still offline.

To try and bring the internet to the reaches of people like Priyanka Singh, a group of global companies have teamed up to try and bring down costs.

Internet.org is a consortium that aims to connect 'the next five billion'.

Mark Zuckerberg at the two-day Internet.org summit held in New Delhi

Perhaps the most high profile partner is Facebook, whose founder Mark Zuckerberg says connectivity is a fundamental right. He came to India this month for the launch.

The number of Indians using the internet jumped by about 25% last year from 2012, but the numbers are still small compared to the population.

And the biggest barrier to changing that is cost.

The next wave of potential internet users is lower skilled workers, like shop assistants, or street vendors.

But earning less than $200 a month, and often struggling to make ends meet, many question whether they can really afford internet access.

"The internet is something that we are uniquely suited to help spread," says Mr Zuckerberg.

"We are an information technology company and an internet company. We understand these dynamics well."

Shopkeepers are among the next wave of people likely to use the internet

For people like this street tailor, getting online can be simply too expensive

Phone smarter

More than 80% of India's access is now via mobile phones.

But connections can be painfully slow, especially in crowded places. This does nothing to encourage new users.

Swedish equipment maker Ericsson is working on ways to improve connectivity without the need for expensive infrastructure - like technology to boost existing mobile signals indoors.

Called the Radio Dot System and the RBS6402 picocell, these are devices which can be fixed in places like shopping malls, sports arenas or even big office buildings.

Christian Hedelin, who heads the radio unit in Ericsson, says as smartphones get more affordable, the number of users is rising.

"To carry a large amount of voice traffic is one thing, but when people start using smartphones, everyone starts to want a good mobile broadband connectivity," he says.

The majority of phones in India are used simply for calls - but this is likely to change with smartphone adoption

"That's where you need to have dedicated hotspot coverage through small cells, to be able to cater for both capacity as well as performance."

According to Ericsson, smartphone prices are expected to fall by 40-50% over the next three years.

This means the number of subscribers able to afford smartphones and services is expected to reach more than 700m by 2020, up from 110m in 2013.

But telecom operators in India are already struggling, with overstretched networks creaking under pressure of data demand from subscribers.

Despite being one of the largest telecom markets in the world, with more than 900m mobile phone users, operators in India have far less spectrum than global companies.

So Ericsson says with a mix of small cells like theirs, wi-fi hot spots could complement networks to improve quality of performance for users.

The BBC's Shilpa Kannan speaks to Ericsson's Christian Hedelin (right) and others about connecting India's poor

Big data

Currently India is still largely a voice market, and data only contributes 10-12% of revenue. But this is expected to rise to 35-40% by 2020.

Ericsson also predicts that the mobile broadband subscriber base in India could grow to 600m by 2020, from around 100m now.

Telecoms operators seem to agree.

Like Norwegian firm Telenor, which currently owns a stake in its Indian venture Uninor, but is set to buy the company fully, after a government decision last July to remove restrictions on foreign ownership in local telecoms companies.

This will make Telenor only the second firm after Vodafone to have a 100% foreign-owned telecoms company in India.

Telenor's global chief executive Jon Fredrik Baksaas says the company will invest nearly $13m.

Uninor is still a small player, with just 40m mobile subscribers, operating in only six of the country's 22 telecom service areas.

This year it has extended networks by deploying 5,000 base stations and has seen 40% growth.

Mr Baksaas says the Indian government must try to make more spectrum available if it wants to realise its vision of Digital India.

"[It] has strong plans to grow the economy going forward under the vision of 'Digital India'. Telecom is an enabler of economic growth," he says.

Problems such as a reliable power infrastructure will also have to be solved to let boys like this get online

The Narendra Modi-led administration's ambitious plan is to offer government services to all Indians online, including through smartphones by 2019.

So the company will be looking to bid for more spectrum soon.

Back at the slum, whether the push comes from government or business, the sooner they can get more regular internet access, the quicker these students can put their new-found skills to good use.

The newcomers to the online world say owning a smartphone one day is a far more likely ambition than having a computer.

But when we visited, the students had what they say is a regular occurrence - a power blackout.

Unless India finds solutions to some very basic problems, despite the government programmes and industry push, reliable and affordable internet access will remain a distant dream.