The man who built the Hotel Chocolat empire

- Published

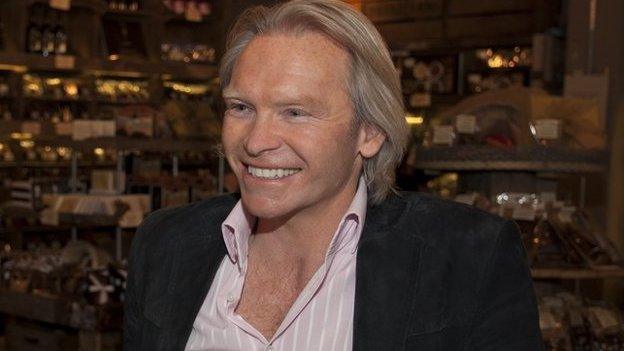

As the son of the man who helped build the Mr Whippy ice-cream brand, it may seem that Angus Thirlwell was destined for a career in confectionery.

But the co-founder and chief executive of UK chocolate shop chain Hotel Chocolat says he was actually inspired to set up his own business after seeing the success of his father's other company - a printing firm.

Since the first Hotel Chocolat store opened in 2004 the company has gone on to grow into a multi-million pound empire, with 81 shops, eight cafes, two restaurants, and a hotel.

As soon as Mr Thirlwell, 51, starts talking, there's no mistaking what drove the firm's evolution. He speaks about chocolate with such evangelical zeal he is bouncing up and down in his chair.

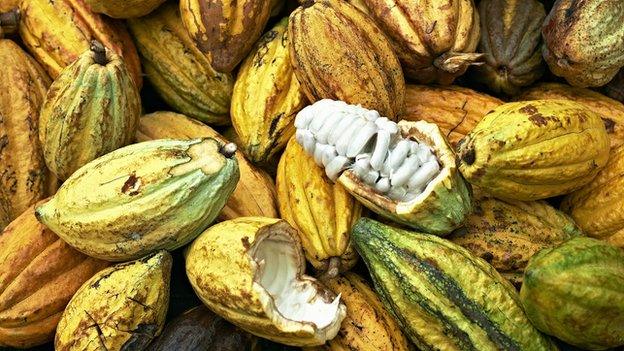

Talking wistfully about the 18th Century, when chocolate houses were all the rage in London, Mr Thirlwell admits that his fantasy is to "make cocoa the hero" again - educating people to recognise and appreciate the higher cocoa content in the chocolate Hotel Chocolat produces compared to some of the best-known brands.

"We want consumers to be having the same debate about the flavours of different cocoa beans as wine," he says.

Mr Thirlwell's desire to educate extends to leaving chocolates he thinks people should like on the shelves even when they're not selling. The firm's 100% dark chocolate products, for example, took five years to become profitable.

Yet using large amounts of cocoa doesn't come cheap, and the firm's "Signature Cabinet", which has three drawers full of chocolates, costs a whopping £160.

But Mr Thirlwell says the pricing makes sense if you look at the cost of the cocoa hit, as well as the packaging. He points out that by contrast, the firm's entry level "Selector" range starts from £3.75.

Mr Thirlwell wants to reconnect chocolate to its key ingredient - the cocoa bean

"It's very important to us that we're accessible," he adds.

Such a wide-ranging pricing structure seems to work with customers, as the company enjoyed sales of £70m in the year to the end of June 2013. And it is continuing to expand apace.

Hotel Chocolat's rapid development has been helped by the creation of innovative chocolate bonds, through which it has raised around £5m from investors, to whom it pays "interest" in chocolate.

Mint business

Mr Thirlwell picked up the business bug working for his father's printing firm in his school holidays. He says it gave him a strong sense that running a company was "exciting".

Nonetheless, he "didn't have a clue" what he wanted to do with life until he got a job at a French hi-tech firm as part of his French and economics degree.

The lure of business was so strong, he dropped out of his course altogether, staying on in France to help the company export its products.

It was on his return to the UK that Mr Thirlwell met Hotel Chocolat's co-founder Peter Harris, who interviewed him for a sales and marketing job at another tech firm.

They hit it off so well that just 10 months later, they left together and in 1987 set up Hotel Chocolat's forerunner - The Mint Marketing Company (MMC), which sold packaged mints branded with company logos.

Hotel Chocolat sells many affordable chocolates, but also some rather expensive ones

Mr Thirlwell got the idea for the business after his father told him that the most successful promotion the printing company had been involved with was for such a product.

To fund MMC Mr Thirlwell and Mr Harris both took out £5,000 personal loans.

Unfortunately, the wrapping machine they'd bought didn't work, and they had to hand wrap 20,000 packs to make their first order.

Mr Thirlwell admits many people would have seen this as a sign that it wasn't meant to be, but he says that this is "rubbish".

"Lots of businesses have some early setbacks," he says. "You've just got to overcome them somehow.

"These things happen all the time even when you're established. You just swat them away more easily."

Diversification

MMC evolved into Choc Express when their customers asked if they had anything beyond mints, and they started selling chocolates online in 1993, becoming one of the UK's earliest e-retailers.

All Hotel Chocolat's chocolates are made at its factory in Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire

Then in 2004 they opened their first store in Watford, after changing the name of the business to Hotel Chocolat.

But why would a retail business wish to call itself a hotel?

Mr Thirlwell says: "It was aspirational. I was trying to come up with something that expressed the power that chocolate has to lift you out of your current mood and take you to a better place."

"Everyone agreed 'chocolat' sounded better than chocolate. It's almost onomatopoeia, and suggests how the chocolate melts in your mouth."

A decade later, the business does own a hotel, which it built in Saint Lucia beside its own cocoa plantation, which provides some of the cocoa for its chocolates.

The company also now has two restaurants, one in London and one in Leeds, serving sweet and savoury dishes that include cocoa. Plus it has stores in Copenhagen.

And from originally outsourcing production of its chocolates, Hotel Chocolat now makes them all itself at its own factory in Cambridgeshire.

Despite Hotel Chocolat's expansion, not a single part of the range gets onto the shelves without first being approved by Mr Thirlwell.

The Hotel Chocolat brand recently celebrated its 10th birthday with a giant rocky road slab-style cake

He chairs a tasting session every Wednesday, where they try new recipes and combinations, and calls this the "triage" of the brand quality.

"It's the beginning of the product, so if I let anything past there that I'm not happy with - it could affect the brand."

Customers can also get in on the act via the firm's Tasting Club - a monthly box of new chocolates which members test and score.

The club now has 100,000 members who have given the business a vast range of data on the public's tastes. A chocolate containing thyme oil has so far scored worst, generating "sackfuls of mail".

"But if you get bull's-eyes for all of them you almost think you're not pushing the boundaries enough," says Mr Thirlwell.

He admits pushing boundaries is also part of "future proofing" the business.

"If you're specialist you've got to be absolutely specialist. There's a lot of competition and we want to be in the driving seat."