The dos and don'ts of leading a fast-growing firm

- Published

Moving at speed requires great skill if you're not going to crash

Chinese firm BYD, short for Build Your Dreams, has a particularly apt name.

It started out in 1995 as a maker of rechargeable batteries with just 25 employees. Its batteries soon became standard parts for a large number of the world's mobile phones, and it rapidly expanded into cars and solar energy.

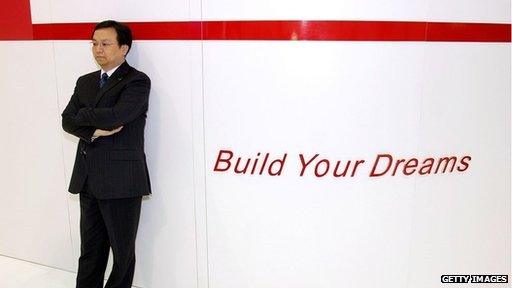

By 2009, founder Wang Chuanfu was China's richest man with a net worth estimated at $5.8bn (£3.6bn) and the firm employed some 150,000 people.

World renowned investor Warren Buffett also bought a near 10% stake in the firm.

In less than two decades BYD had come from nowhere to become one of the largest firms in China.

In 2009 BYD founder Wang Chuanfu was China's richest man

And then it suddenly faltered. Profits fell sharply and in 2011 it was forced to lay off significant numbers of its car sales staff.

"In 2008 and 2009, the growth rate of China's car market almost reached 40%, disguising our problems in retailing. As the growth rate slowed down, we had to face those problems," says Mr Wang.

He admits the firm "grew too fast". Its decision to move into cars meant it had to switch from selling its products to other companies, to selling directly to consumers - a completely different proposition.

It opened too many dealer networks too quickly, many of which made a loss.

Getting its rate of expansion right took three years to fix, but Mr Wang says the firm is now back on track.

"It was a good path, [I] just had to persevere through it," he says.

China is growing much faster than its western rivals

While it's easy to suggest this is hubris getting its just reward, in China, this extraordinary rate of expansion - or hyper growth - is relatively common.

When the Chinese government began to open up the economy in the 1980s, it rocketed from a small emerging economy to a heavyweight, growing many times faster than its western rivals. Yet as BYD demonstrates, such rapid expansion makes it hard for some companies to adapt quickly enough.

"Once a company is in hyper growth mode it's important not to lose sight of what made the firm a success in the first place," says leadership expert Steve Tappin.

Victor Koo, chief executive of video-sharing giant Youku Tudou, often dubbed China's YouTube, has seen dramatic changes since it launched in 2006.

Initially, its users were accessing content almost entirely on desktop computers, now more than 60% of users access content via their mobiles.

Youku Tudou boss Victor Koo says the firm has learnt not to overthink things

To ensure its firm could react quickly enough to take advantage of the rapid changes, its philosophy used to be "do before we say and think before we do". But now, Mr Koo says, that is just not fast enough.

As a result, it has shaken up its organisational structure to create "quick task teams" which work across different departments, can brainstorm ideas and come up with new ways of doing things.

"If you overthink it or you spend too much time thinking about it the opportunity has already passed. And as you experiment [and] explore, your strategies actually formulate themselves. Don't sit still".

For an eight-year old firm like Youku Tudou, where ways of working are less established, it can be easier to embrace a more flexible approach, but for older firms it's often harder to shake up the status quo.

Weibo was listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange earlier this year

Online media company Sina Corporation was established 15 years ago and listed on the Nasdaq, the US technology exchange, soon after. This year it listed Weibo - its Twitter-like micro-blogging service - on the Nasdaq in a separate listing.

Chairman Charles Chao says that because Weibo was part of Sina, its value and the fact that it was growing much faster than its existing businesses, had not been recognised by investors. The separate listing was aimed at addressing this.

But right from the very outset, he says they tried to keep the businesses separate, because Weibo was a very different business to Sina and he didn't want the original company to hold back innovation at the new firm.

"I don't think there's a scientific way or a bible you can follow in terms of how to run a high growth company. Our approach is that we separate, we try to create a system that more resembles start-up companies."

Deng Feng says having a good internal culture can help firms thrive in a period of rapid growth

Deng Feng, chair of Northern Light Venture Capital, a Chinese venture capital firm, says ultimately what can help firms survive or even thrive in a period of rapid expansion is having the right internal culture.

He started his own firm in Silicon Valley at the end of 1997 and listed it on the stock exchange just four years later.

Despite its ultimate success, he said during the four years there were three occasions when it was close to collapse, due to key people leaving and because at times it had "no money in the bank". At one point it was acquired by another firm which subsequently collapsed. In the end, it managed to get out of the acquisition.

"Head hunters tried to recruit them [the staff]. Here, the Chinese culture actually helped. The key engineers that were Chinese, they stayed together and they helped the company and we solved the problem," Mr Deng says.

This feature is based on interviews by leadership expert Steve Tappin for the BBC's CEO Guru series, produced by Neil Koenig.