Meet the metal detectorists saving marriages

- Published

With this ring: Wedded bliss doesn't necessarily mean it's all plain sailing - and a row can quickly escalate into a ring pitched into the ether, only to be bitterly regretted later

It's 09:00 on a cold, wintry Sunday morning and a strong wind is blasting across a recently ploughed farmer's field.

We are somewhere down a beaten track on the Purbeck clifftops along the UK's south coast. The landscape is deserted, with the exception of one determined man with his metal detector… and me.

Flying instructor Richard Higham is a treasure-hunter in his spare time, and he is convinced this particular field is a "hotspot" for relics from the past.

He points out the visual clues which suggest somebody once called this deserted, exposed spot their home.

Burial mounds, pottery shards, flint and overgrown but still distinctive stripes along the slopes of the landscape - the remainder of an ancient farming method.

His metal detector - a middle-of-the-range model compete with GPS - goes on and we begin our march, hunched into the wind.

Metal detectorist Richard Higham hunts for buried treasure on the clifftops of Dorset

Mr Higham ignores most of the machine's many burbles and squeaks - it can differentiate between various metals and most are not worth unearthing.

We could be here for some time, he warns.

"On a good day you might find eight artefacts. Around 25% of those finds will be any good."

His longest treasure-hunting session lasted 14 hours, but on this occasion either luck or Mr Higham's detective skills are on our side.

Within 45 minutes his metal detector emits a high-pitched, wavering sound like an electric guitar being tuned - and shortly after I'm holding a tiny, green mis-shapen coin in the palm of my hand.

Our find: a coin around 1,800 years old

Richard Higham guesses the copper piece, complete with a distinctive Roman emperor's head gazing back at us, was made somewhere between 160-260AD.

"You are the first person in 1,800 years to hold that coin in your hand," he says dramatically.

It's certainly a thrill, but for Mr Higham treasure-hunting extends beyond a personal fascination with history.

Rings reunited

He belongs to a global collective called The Ring Finders, external - an online directory of more than 250 metal detectorists who try to reunite people with lost jewellery. All that most of them ask for in return is travel costs and a donation to charity.

It was founded by Chris Turner, who lives in Vancouver.

He keeps a video blog of his successful reunions, and claims the Ring Finders have retrieved more than 1,500 pieces of jewellery worth a total of $3.6m since he launched in 2009.

Metal detectorists have become a common sight at the end of the day on some beaches

Recalling the case of a woman who lost a diamond wedding band, he identified a common cause of misplaced rings.

"...she got mad at her husband and tossed the ring into a grassy area by the college," he wrote in a blog post, external.

"Believe it or not that is a very common thing that people do. You never see many people on my videos talking about this because they don't want to be seen or talk about such a search."

Mr Higham also recalls a couple who called in his services after a ring had apparently ended up in a river after a row - but all was not as it seemed.

"It was the man who rang me. Then she rang me back and said she hadn't actually thrown the ring, she'd pawned it," he says.

She wanted to get a replica made for him to "find" as arranged.

"I decided not to get involved in that one," Mr Higham says diplomatically.

All that glitters

While many in the metal detecting community are not in it for the money, it's an industry that's proving fruitful for the manufacturers of their tools.

One of the big brands, Minelab, reported revenue of $70m in 2012 from sales in its three core divisions - consumer metal detectors, equipment for small scale gold miners, and countermining - or the hunt for unexploded IEDs.

Metal detectors are vital for finding hidden mines and other buried threats - here, a Brazilian soldier searches for buried weapons in a slum Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

"The consumer business covers primarily hobbyist metal detecting. Historically people would have termed it a first world activity - America, Western Europe, Australia," says regional sales manager Vincent O'Brien.

"We're now seeing growth in new territories - Russia is a big market for us, Eastern Europe, Latin and South America."

Detecting equipment for small scale mining for gold nuggets is growing in popularity across Africa, Asia and South America, he added.

"You could say over the last maybe five to seven years gold has shot up significantly, that interest in gold has reflected in the interest in our machines. There is probably an awareness of the value of gold in Africa where perhaps there wasn't before, in some countries gold was always there but it was ignored when diamonds were in vogue shall we say."

A report , externalby media organisation Business Africa, external which featured Minelab found that for some amateur metal detectorists in Africa, the rewards could be life changing.

One treasure-hunter in Burkina Faso, named only as Souleymane, said he had found enough gold to purchase three plots of land, three motorbikes and three more metal detectors... in addition to putting his 10 children into school.

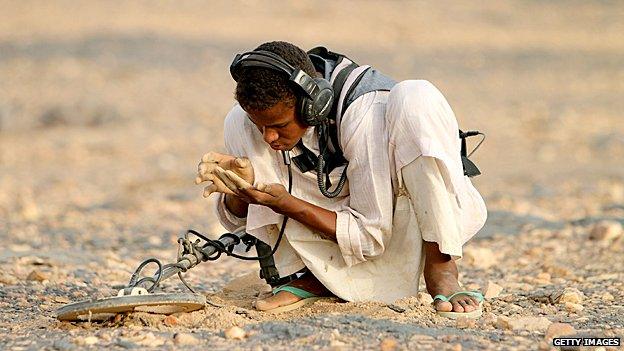

Metal detecting is becoming more popular in Africa, specifically for hunting gold - as this Sudanese man is doing

It's not just Africa where the hunt for gold is driving metal detector sales. This man is hunting for the legendary gold hoard of Francisco Solano Lopez, a Paraguyan military hero

Magnetic magic

But has the humble metal detector really evolved that much?

Alexander Graham Bell designed and used a metal detecting device in 1881 - and he wasn't the first.

Fundamentally metal detectors work by generating an electromagnetic field which is transmitted into the ground. Any metal that comes into contact with it generates its own field which the detector picks up.

"In recent years there has been a lot of advancement both in the machines and the type of people using them," says Vincent O'Brien.

"Traditionally our typical customer was male, middle-aged, semi-retired - that image of metal detecting on the beach.

"Nearly all the newer machines have digital interface, they're lighter, easier to use. Our more recent machines have in built-in GPS that you can use in conjunction with Google maps, and wireless capabilities."

Whether the new connectivity is actually translating into increased treasure finding is debatable, according to Dr Michael Lewis who looks after the Portable Antiquities Scheme run by the British Museum.

Launched in 1997, it aims to keep records of amateur finds around the UK - and recently recorded its one millionth find.

Dr Michael Lewis with a 15th century Pilgrims badge, a find sent by an amateur metal detectorist to the Portable Antiquities Scheme

"Manufacturers will say their machines are getting better and better, but the reality is it's technique I think," said Dr Lewis.

"You come across some detectorists who are very good at finding stuff, others spend ages in a field and find nothing."

But whatever your equipment, if your dream is to find actual treasure (defined in the UK by the 1966 Treasure Act, external - it does not include individual coins) you need more than Google maps on your side.

"Last year at the Portable Antiquities Scheme we recorded 80,000 finds," he said.

"Maybe 1000 were precious metals. People do find the odd silver coin but the amazing archaeological discoveries are quite rare."

- Published13 October 2014

- Published3 October 2014

- Published23 August 2014