US targets debts for dead-end degrees

- Published

President Obama, speaking at a college in Rhode Island, wants to stop students being trapped by debts

Is going to university a way of getting on a ladder of opportunity? Or is it a way of descending into debt that will outweigh any promised advantages?

It's a question that faces every developed economy where going to higher education has moved from an academic minority to a mainstream career pathway.

In the United States, where student debts have spiralled through the trillion dollar barrier, the Obama administration has announced regulations designed to curb the risk of debt from courses that do not deliver any worthwhile career benefits.

From July 2015, universities and colleges will be tested to see whether they deliver value to students' future earnings or else risk losing federal funding.

It's meant to stop the toxic combination of high repayments and poor career prospects.

"Career colleges must be a stepping stone to the middle class. But too many hard-working students find themselves buried in debt with little to show for it. That is simply unacceptable," said US Education Secretary Arne Duncan.

The education department says it wants to stop excessive costs for training that leads to low-wage jobs or unemployment.

Balancing repayments

The education department estimates that more than 800,000 current students are on courses that would fail this value-for-money test. And 99% of these students are taking courses run by for-profit colleges.

Arne Duncan: "Too many hard-working students find themselves buried in debt"

The benchmark will be a ratio of debt repayments to earnings. Full details will be published later this week, but it will mean that typical graduates should not face debt repayments of more than 8% of total income or more than 20% of disposable income.

If college debts are above these thresholds then they might be labelled as failing to prepare students for "gainful employment" and the college could lose access to federal funding.

It's an attempt to unpick the thorny relationship between tuition fees, debt and student loans.

But the measures have drawn criticism from both sides.

The for-profit colleges have hammered the plans as being a barrier to poor students trying to improve their qualifications.

'Arbitrary and capricious'

Steve Gunderson, president of the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities, said it was a "bad-faith attempt to cut off access to education for millions of students who have been historically under-served by higher education".

He attacked the debt-to-earnings ratio as "arbitrary and capricious" and launched a lobbying campaign to block the regulations.

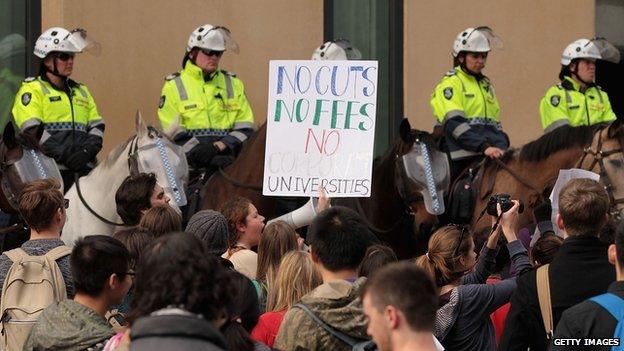

In Australia, changes to university funding have been met with protests by students

But there were other critics saying the regulations were too weak.

Rory O'Sullivan, deputy director of the Young Invincibles lobby group, said the Obama administration had "caved in" to private providers.

He said the thresholds should include the level of defaults on loans, including students who dropped out without graduating but still faced repayments.

The United States Student Association also complained the rules left the funding system "rigged" against students.

In many ways the US pioneered the modern university system, the first in the world to have mass participation in higher education.

And now it is having to pioneer ways to cope with the levels of debt.

Global challenge

It is a challenge for all developed economies because student numbers are likely to carry on rising.

The OECD economic think tank has consistently argued that the job markets in industrialised countries will require more graduates.

Festival of lights in Berlin: Universities in Germany have scrapped tuition fees

There is a strong aspirational demand for higher education among young people - and the OECD suggests this is a well-founded ambition, because graduates continue to earn more than non-graduates.

But it raises the question of who is going to pay for more university places? How much should individuals contribute? And if governments want to provide access for poorer students, how do they make sure the taxpayer is getting value for money?

The university system in Germany has shifted in an entirely different direction this autumn - getting rid of all tuition fees.

In England there are conflicting messages - with some calling for fees to rise, while others propose cutting fees. Scotland so far seems set to remain without tuition fees - and it remains uncertain how any change in England would affect fees in Wales and Northern Ireland.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, says the US attempt to control student debts is part of a difficult balancing act.

"The challenge is to ensure that any changes designed to make institutions more accountable and to protect taxpayers do not also inhibit people from studying higher education courses with low private returns but high public returns - like nursing, for example."

In Australia, there have been protests about plans to remove limits on tuition fees.

Student debt in the US has quadrupled in a decade - but there have been arguments that debt is not always bad news.

US Deputy Treasury Secretary Sarah Bloom Raskin said increased student debt reflected more people going into higher education, which was a good investment for individuals and the economy.

Universities were also charging more, she said, with tuition in US universities 50% more expensive in real terms than in 1994. University fees can be above $50,000 (£31,000) per year.

Good student borrowing, she told students in Maryland earlier this term, was "an engine for continued income mobility and economic growth".

The bad variety was illustrated by a graduate from a Florida law school with student debts of $200,000 (£125,000). "I can't buy a car," said Kris Parker. "I have a hard time buying furniture."