Whatever happened to the Brics economies?

- Published

Oil is key to the Russian economy

Remember the Brics - Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, the nations that were set to reshape the world economy?

Two of them, China and Russia have the potential to cause some serious and rather unwelcome reshaping in the near future.

In China's case it's the risk that an economic slowdown could turn into something more damaging.

With Russia, it's the possible economic fallout from the conflict in Ukraine.

Four of these five countries - South Africa is the exception - were identified in 2001 as large and fast-growing economies that would have increasingly influential global roles in the future.

Today it's China and Russia that are potentially the most troubling for the rest of the world in the near term.

China's story is one that we would inevitably have had to face sooner or later. Indeed you might say it is remarkable that it hasn't come sooner.

China has recorded extraordinary rates of economic growth for a very long time - an average of 10% a year for three decades.

But there are weaknesses. It's based on very high rates of investment, currently running at 48% of national income or GDP.

When it's so high there's always a danger that many projects will turn out to be wasteful or unprofitable, undermining the finances of the investors themselves and anybody who has lent them money.

Only a handful of countries have higher rates of investment, none of them with much to teach China. They are Bhutan, Equatorial Guinea, Mongolia and Mozambique.

The other element in China's rapid growth is exports.

That is not so reliable these days as the rest of the world struggles to recover convincingly from the financial crisis.

Chinese transition

What the Chinese government wants to do is move towards economic growth that's a bit slower and driven more by selling goods and services to Chinese consumers.

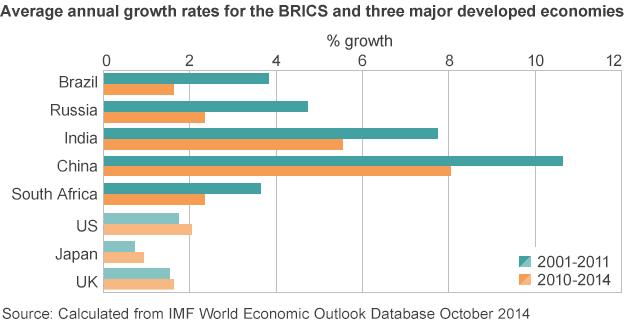

The slowdown is happening. Already this decade, the average growth rate has slipped by more than two percentage points.

The man who dreamt up the term "the Brics", Jim O'Neill formerly of Goldman Sachs, thinks the transition can be managed without too much turbulence.

Others are more wary.

Prof Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard University says China's slowdown is both inevitable and desirable but he warns:, external "It is not easy to rein in growth gradually without triggering widespread failure of ambitious investment projects."

He says that if Chinese growth collapses the global fallout could be far worse than that caused by a normal US recession.

Russia is a very different story.

Its potential economic impact on the rest of the world in the near future is at heart about political issues.

The conflict in Ukraine has already set back Russia economically.

The sanctions imposed by the west, and the anxiety among investors that there might be more, have aggravated a slowdown that was coming anyway.

Some $85bn (£55bn) has been pulled out of Russia this year, external, according to Central Bank figures.

Russia is often criticised for having a difficult business environment - red tape and uncertainty about the legal system.

The IMF has made the point before , externaland Jim O'Neill says Russia needs a credible rule of business law.

Russia's problems have already had an economic impact beyond its borders, notably in Germany.

Exports to Russia have fallen sharply, external, which is one important factor behind Germany's close shave with recession.

Looking ahead, the IMF has also warned that "geopolitical risks", which means the Ukraine crisis and the Middle East, are one of the main threats to a global economic recovery that is already, in the IMF's own words, "weak and uneven", external.

Indian momentum

Another one of the Brics with clear problems is Brazil, though it poses less of an international danger.

Sugar is one of Brazil's important agricultural commodities

Like Russia, it's an economy where commodities exports have played an important role in the successes of the 2000s. In Russia it was oil and gas.

Brazil has iron ore and agricultural commodities such as soya, coffee and sugar.

Jim O'Neill says that both need to take steps to make themselves less dependent on the commodities business.

They need to improve their labour competitiveness, he says, and to make themselves more attractive for private investment in other industries.

Among the original Brics countries - which did not include South Africa - India seems to be causing rather less anxiety in financial markets and international economic institutions at the moment.

Growth has picked up some momentum this year although it is well short of the highs of the previous decade.

Many investors have welcomed the new government of Narendra Modi, external, which took office in May.

Jim O'Neill says: "I am more optimistic than I have been for some time about India."

So are the Brics crumbling?

It's worth recalling where this concept came from. It first saw the light of day in a paper written in 2001, external by Jim O'Neill.

It wasn't a club, just a convenient way with a nice acronym for spotting important trends.

It was years before the countries started holding annual summits and at that stage it didn't include South Africa. The "s" was just there as a plural.

Catch up growth

The point of the paper was to show the increasingly influential role these countries would play in the global economy over the following 10 years and to argue that international economic co-operation should change to reflect that changing reality. And it has.

Since 2008 one of the key forums for economic policy issues has been the G20 group of countries that includes all the Brics among its members.

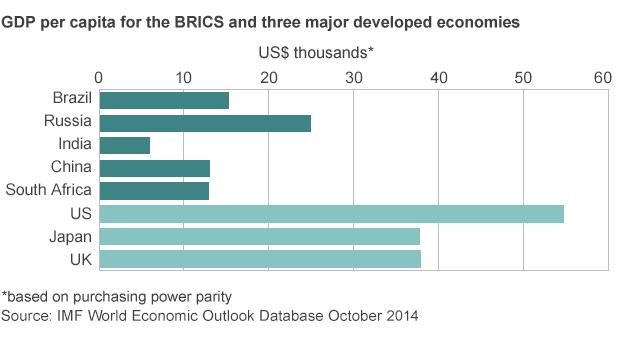

The Brics were the largest emerging economies. There was no African country when the idea was first used, and in terms of its economic weight South Africa was well behind the others, and behind some that weren't included such as Indonesia and Mexico.

A follow up paper, external by two other Goldman Sachs economists took the analysis up to 2050 and suggested that the Brics collectively could be larger than the six leading industrial countries combined by 2039.

Strictly speaking, the Goldman Sachs papers weren't forecasts. They were pictures of what the world might look like if the countries grew as they might.

The growth rates envisaged were much stronger than for the rich countries.

They have the scope to "catch up" by investing rapidly in technology that is already established in more developed economies.

The chart gives an indication of how the Brics still have further to go. It shows GDP (economic output) per person, which gives an indication of the level of economic development.

There are also two factors that mean there's a ready supply of workers for fast expanding industries - growing populations and urbanisation as people move from the countryside to the cities.

In those original projections from Jim O'Neill, Chinese growth over the next 10 years was set at 7%, India 5%, Russia and Brazil both at 4%.

In the event Brazil was just short of its figure, while the others all beat theirs.

But all the Brics have slowed in the current decade, by more than two percentage points each, with the exception of South Africa.

Potential for the future

The IMF has done some research, external on the slowdown in the developing world.

A significant part of it reflects weaker international demand for their exports and government policies in the countries themselves becoming a restraint on growth as they reversed earlier stimulus policies - cutting spending or raising taxes to reduce borrowing needs.

But there are also factors that affect emerging economies' capacity to grow in the future - that constrain what the IMF calls their "potential growth".

China's one child policy is being eased

Interest rates are likely to rise gradually from their current ultra low levels in the rich countries - particularly in the US and the UK.

That will affect global rates and make investment more expensive to finance in emerging economies.

Many also have to contend with ageing populations and slower growth in the number of people of working age.

For some that demographic advantage they had previously is now fading.

Russia and China are among that group. That was factored into the Goldman Sachs projections. Jim O'Neill says that more recently their policies in this area have been "surprisingly good".

China is easing its one child policy and, he says, "Russia has had some success in raising life expectancy with much smarter policies about alcohol consumption."

While all the Brics have slowed this decade, the weakest performers now are Brazil and Russia.

Their average growth rates have been below the Asian Brics all along and this year they slowed even further. For 2014 as a whole, the IMF has projected some growth, external for those two but very little - 0.3% for Brazil and 0.2% for Russia.

Both those figures incidentally are a good deal weaker than what has been predicted this year even for the struggling eurozone, which has been described as haunted by the "spectre of stagnation" by the Bank of England governor Mark Carney., external

As for Russia and Brazil, Jim O'Neill is not yet ready to wipe these two nations out of his Bricspicture, but the last few years have certainly been a disappointment.

So it is not time to write off the Brics.

They are showing some cracks for sure, and, to change the metaphor, China in particular is embarking on a high-wire journey as it seeks a different and perhaps ultimately more sustainable form of economic development.

The Brics and how they perform matter for the rest of the world, more so than they did at the turn of the century, which is after all the whole point of the original idea.

- Published17 November 2014

- Published15 July 2014

- Published14 July 2014

- Published11 July 2014