The German way of stagnating

- Published

- comments

In Germany, why is is that they seem to do most things better than the rest of the world, even economic stagnation and recession?

I was in the great port of Hamburg yesterday, part of the industrial powerhouse that is Germany, to get a sense of the mood of the country, shortly before the publication of official figures that will show the German economy is pretty limp.

In the second three months of this year, German national income contracted by 0.2%, and it is widely expected that it either flatlined or shrank a miniscule amount in the three months to the end of September.

So Germany is either in an official recession - albeit a mild one - or so close as to make precious little difference.

Surely therefore German business owners, economists and people would be gloomy. After all, in the UK, whose economy is growing at a world beating pace of 3% a year, the general mood is still on the grim side - opinion polls show we are a bit more upbeat than we were, but we are not exactly ready to partay (sic).

Now of course there was no science involved in the selection of the Germans to whom I spoke, so I am not claiming that my Hamburgers precisely capture the mood of the nation.

But it was nonetheless striking that everyone to whom I spoke - from the owner of a goodly sized "mittelstand" international manufacturer, to students, to workers and professionals - were all confident about the economic future, and felt their government was doing roughly the right thing.

More pertinently, they see the current slowdown as a temporary thing. And they apparently have no desire for the government to waver from its course of eliminating its budget deficit next year.

It is not clear to me whether Hamburgers are listening to to Mrs Merkel or she is listening to them - but either way she seems to be in tune with them to a degree that presumably would make Mr Cameron sick with envy.

Here is perhaps the most extraordinary difference between the UK and Germany.

German leader Angela Merkel's economic policy is apparently in tune with the mood of her nation

The UK national debt continues to rise pretty rapidly as a share of national income, despite putative austerity that divides the nation and the main political parties.

By contrast in Germany the national debt has already been falling as a share of GDP in recent months. and belt-tightening seems to be viewed with calm and equanimity, as more or less a national duty.

Now to be clear, this German sangfroid and - some would say - complacency is not necessarily good either for them or the rest of the world, in the long run.

There are those, such as Marcel Fratzscher, head of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), who fear the country has been making false economies, by cutting back on important infrastructure spending and investment - and that this will in time undermine its formidable productivity and competitiveness.

The DIW calculates that Germany's public sector and private sector need to make additional investments worth more than 100bn euros every year, just to maintain the existing stock of productive capital, road, rail and so on.

Despite the fact that Germany invests considerably more than the UK, Fratzscher believes Germany has been under-investing for well over a decade.

And then there is there is the question of the sustainability (a very German concept) of its basic economic model - which is to sell massively more to the rest of the world than it buys from the rest of the world.

The extraordinary thing is that in 2013, Germany had the biggest trade surplus in the world, of 206bn euros - bigger even than China's (by a fraction).

This dependence on exports means of course that when growth in the rest of the world slows, as it has been doing, growth in Germany has to slow. And that of course is what has been happening for most of this year - as much of the eurozone has hit the buffers (again) and China's attempt to become less dependent on debt-fuelled investment has seen its growth decelerating.

For Germany, there is the added factor of its close trading ties with shrinking and blackballed Russia.

So that is the short term cost to Germany of being so hooked on exports - although I have to say my experience in Hamburg yesterday was of a nation not unduly fussed about that.

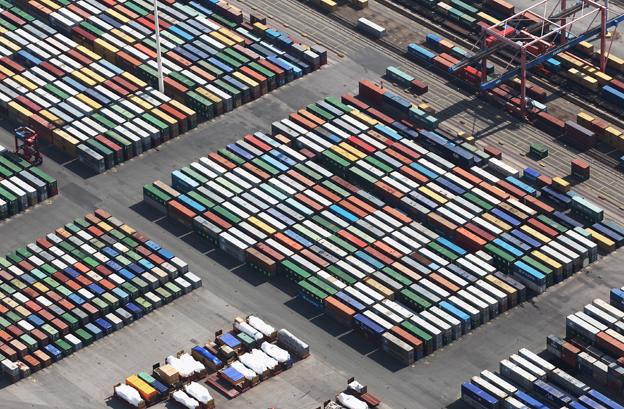

Shipping containers at the port of Hamburg: Is Germany "hooked on exports"?

It is the rest of us who should perhaps be bothered.

When the world divided, as it did before the great crash of 2008, into great surplus-producing countries, such as China, Saudi and Germany, and great deficit-generating consuming countries, such as the US and UK, the monetary conditions were created for a dangerous rise in global indebtedness.

With the likes of Germany still attached to that surplus-maximising model, it becomes harder and more painful for the indebtedness of the consuming countries to be reduced to manageable and sensible levels.

Your response may be something along the lines of "hard cheese". That is, in my experience, the typical Germanic response.

The view of many Germans is that the likes of the UK, France, Spain and so on lived for years beyond their means. And it is therefore perfectly reasonable for them to make some sacrifices today, to get their (our) finances back in shape, at the level of state and households.

But if a surplus country like Germany isn't prepared to take steps to expand its own economy, by stimulating spending either by its people or government, then the steps necessary for a Spain or a France or an Italy to reduce indebtedness are even more painful.

The point is that the cuts they are forced to make aren't counterbalanced by extra demand for their goods and services from the likes of Germany.

In those circumstances, getting the debt down in the weaker consuming economies leads to international beggar-my-neighbour. Everyone tightens their belts. Global growth slows down. And all countries ends up poorer than necessary - even Germany.

So although German fiscal righteousness and attachment to prudence is completely understandable, it is not necessarily rational.