Headline numbers: Knocking £2.8bn off the deficit

- Published

We've had two examples in the last week of why it's so hard to predict the deficit, which may end up knocking almost £2.8bn off the figure, writes Anthony Reuben.

The public sector deficit is the amount that the government spends minus the amount that it receives in taxes, after you've taken into account investment.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast of whether the deficit will go up or down in the current financial year will be a big focus in the Autumn Statement on 3 December.

At the end of last week, it looked as if this year's deficit would be going up by £1.7bn as a result of a backdated bill for UK contributions to the EU Budget.

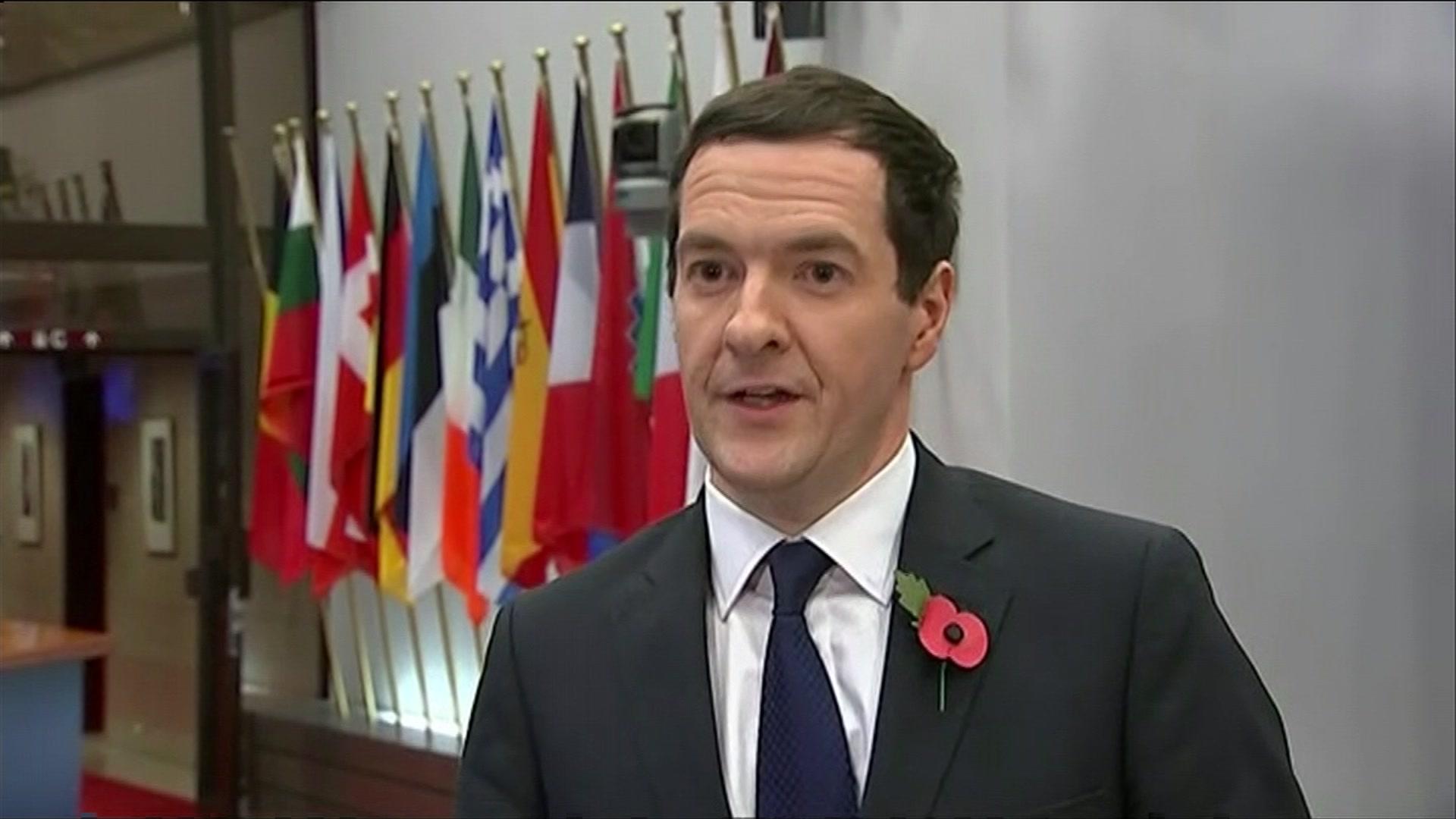

But then, as a result of Chancellor George Osborne's negotiations, it turned out that we would have nothing to add to this year's deficit and "only" £850m to add to next year's, which would be after the general election.

On Wednesday, the Treasury discovered it would be receiving an extra £1.1bn (minus costs) as a result of the fines imposed on banks by the Financial Conduct Authority for traders' attempted manipulation of foreign exchange rates.

Mr Osborne said that the fines would be used "for the wider public good", which could mean they go towards reducing the deficit. Alternatively, as was the case with the Libor fines, some of the money could go towards other good causes.

The point is, the deficit could go up or down by a billion pounds or so for unexpected reasons, which could make all the difference between a rising deficit and falling one.

In the first six months of the current financial year, the deficit excluding public sector banks, external was £45.7bn, up from £44.8bn in the first six months of last year, but down from £50.6bn in the same period the year before. £2.8bn would have reversed that rise.

We've also recently had a warning from the OBR that it expects to lower its forecast for the amount of tax the government will collect this year.

All this makes it likely that the OBR will predict that this year's deficit will end up higher than last year's, despite government cost-cutting and a growing economy.

And you have to feel the OBR's pain when it attempts to make these forecasts. It has been very wrong with some of its forecasting since it was created in 2010, although admittedly not much more wrong than other forecasters.

Even so, how are you supposed to make forecasts when you never know where an extra billion pounds or two could come from?

- Published12 November 2014

- Published7 November 2014

- Published13 October 2014