Brazil's downturn fails to put off foreign investors

- Published

Jaguar Land Rover was in optimistic mood at the Sao Paulo Car Show

Optimism over the Brazilian economy has been in short supply recently, so when someone bucks that trend it tends to attract attention.

The reasons for gloom are obvious - market analysts expect the country to grow less than 0.3% this year and many critics accuse President Dilma Rousseff of mishandling the economy.

Inflation is close to the target ceiling of 6.5% and everyone wants to see who the newly re-elected president will choose as her finance minister.

But with the dust hardly settled on the election, two Jaguar Land Rover executives met foreign correspondents at the Sao Paulo Car Show to talk about their new manufacturing plant in the country.

And Phil Popham, JLR's marketing director, and Terry Hill, the managing director for Latin America, said they were highly optimistic about the prospects for their business in the country.

"The segment of 'premium cars' has been growing steadily despite deceleration," explains Mr Popham, who says they are looking at the longer-term picture. "Our focus is on the long run."

The JLR plant in Itatiaia is the first wholly owned by the group outside the UK and will start assembling its new Land Rover Discovery Sport in 2016.

It is expected to cost about $290m (£185m) and to create, initially, 400 jobs.

Chinese carmaker Chery International has a new factory in Brazil

But JLR is not the only foreign group looking beyond Brazil's current economic woes.

At the same car show, for instance, both BMW and Chinese firm Chery International presented the models that will be produced in recently inaugurated manufacturing plants in Brazil.

Another Chinese carmaker, Geely Automobile, also confirmed it is looking into opening a factory in the country.

'Several strengths'

Despite sluggish economic growth, foreign direct investment (FDI) in Brazil reached $66.5bn in the last 12 months, according to the Brazilian Central Bank.

That is about the same level that was reached in 2011 - when Brazil was the darling of emerging economies (it had grown at an impressive rate of 7.5% in 2010).

Data from the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) also shows this type of investment in Brazil has increased 8% from January to August from the same period in 2013.

This has happened at a time when, across the region, there has been a decline in FDI of 23%.

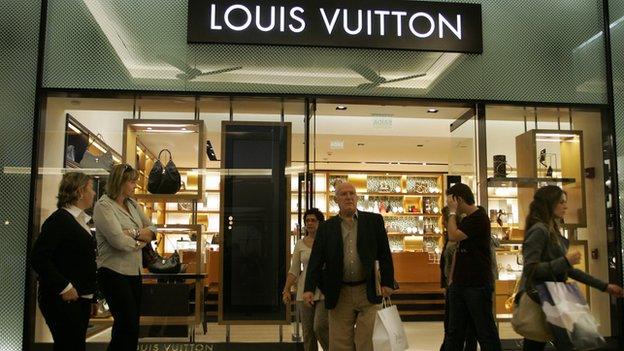

Demand for luxury goods has grown in Brazil

"Some of these investments were indeed planned years ago, when Brazil's growth was stronger," says economist Caio Megale, from Itau-Unibanco.

"But this only tells part of the story. In fact, Brazil's market has several strengths that are sustaining investors' interest despite economic uncertainties - such as its political stability and relatively strong economic fundamentals," he argues.

Irene Mia, regional director for Latin America and the Caribbean for the Economist Intelligence Unit, agrees.

They have plans to open an office in Sao Paulo by the end of the year to "better serve our Brazilian customers and international consumers focused on Brazil".

"Sluggish growth is just part of the story and is not by any means the only criteria on which investors focus their investment decisions. Brazil's attractiveness for FDI remains huge," she says.

Ten-year plans

In recent years millions of Brazilians have been lifted out of poverty, representing a new middle class of consumers. This process has slowed down recently, but is still going on.

The cosmetics market in Brazil is the third largest in the world

At the same time unemployment rates remain at historically low levels, and the economic slowdown has not impacted dramatically on the life and consumer habits of most Brazilians.

"Today Brazil's cosmetic market is the third largest in the world, its automobile market is the fourth biggest and its market for laptops ranks third," says Olavo Cunha, from the Boston Consulting Group.

"Many multinationals feel they need a plan for Brazil for the next 10, 20 years."

Another factor fostering investors' interest in Brazil is that some sectors of the economy - and some geographical regions of the country - are still growing rapidly.

Oil and gas, for instance, continues to attract attention now that the government has concluded the first round of auctions for the exploration of the so called "pre-salt" deep reserves.

Luxury market

Infrastructure is also seen as a promising sector, according to Luis Afonso Lima, president of Sobeet, a think-tank focused on the globalisation of the Brazilian economy.

"It has a huge potential to grow if the government is able to achieve a more business-friendly regulatory environment," he says.

More and more designer brands have entered the Brazilian market

The market for luxury goods is another example. According to a report from McKinsey, the number of foreign luxury brands in Brazil has doubled in the last five years. And yet among the three top brands in the country there are 0.3 stores for every one million potential customers - as opposed to four stores in China.

Meanwhile, JLR anticipates the share of luxury vehicles in the country to rise from 2% to 4-5% of Brazil's car market by 2020. But in rich countries the segment generally represents 10% of the market and has little room for growth.

"Additionally, foreign companies are also slowly discovering the potential for growth outside the capital cities and metropolitan areas," says economist Rodrigo Baggi, from the consultancy Tendencias.

"Spurred by the resources of agribusiness, these interior cities are becoming a new frontier of consumption."

For Marcos Troyjo, co-director of the BricLab at Columbia University, there is yet another factor behind Brazil's attractiveness to foreign investors.

"A car that costs $15,000 in the United States may be sold in Brazil for double or three times this value," he says.

This higher price partly compensates for the costs of the country's greater tax burden, its red tape and troubled infrastructure.

"But companies also have higher profit margins here. They are pressed by Brazil's protectionist barriers to produce in the country in order to access local markets. And once they are in, they are also relatively protected from external competition," he argues.

"Sadly, Brazilians consumers are the ones who lose."

- Published27 October 2014

- Published29 August 2014

- Published8 September 2014