Q&A: Calling time on the beer tie

- Published

Monday's vote ending the beer tie has been called "historic" by campaigners which have said it will help "secure the future of the Great British pub".

Yet pub trade body the British Beer & Pub Association (BBPA) has warned the resulting changes will be "hugely damaging" to the industry and could result in 7,000 job losses.

We present both sides of the argument and look at what will actually change as a result of the vote. Most crucially, what does it mean for the price of beer?

What is a beer tie anyway?

There are two ways of setting up a pub - an individual or group can set it up independently, meaning they have to pay the going market rate for rents etc, but leaving them free to buy supplies, such as alcohol and food, from whoever they like.

The alternative is a tied option meaning that they rent the premises from the pub company or brewery that owns it. The rent and insurance and other items, referred to as "dry rent", are then typically lower than the actual market rate.

In exchange for this discount, pub landlords must buy beer and other supplies from the company that owns their establishment. This is the "wet rent".

Landlords pay a much higher rate for this "wet rent" than they would if they bought their supplies on the open market.

Tied licensees are paying up to 77% more for Fosters, 67% more for San Miguel and 55% more for Heineken, according to research from voluntary consumer organisation The Campaign for Real Ale (Camra).

Pub trade body BBPA says the tied arrangement enables an individual to run their own pub for a relatively small start up cost of around £20,000 compared with the £250,000 required to set up independently.

And pub companies such as Enterprise and Punch Taverns, which between them own 9,000 tenanted pubs, argue this is the only way for many pubs to get off the ground in the first place.

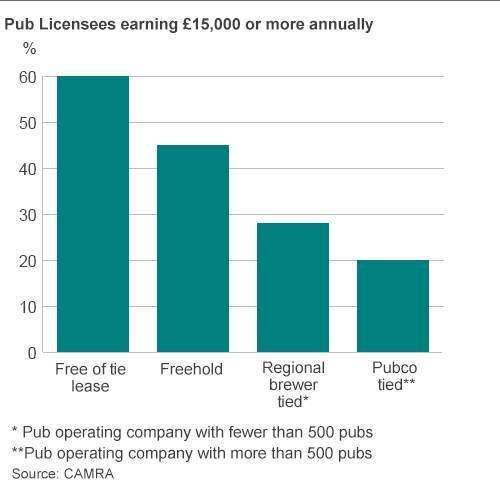

Nonetheless, tied licensees are around £13,000 a year worse off than their untied rivals, according to Camra, with 60% earning less than the national minimum wage equivalent salary of £10,000 a year. And the government's own research suggests that half of the "tied pub" licensees in the UK earn less than £15,000 a year, which is indicated as the minimum starting salary for an employed licensee by the Government's National Careers Service.

How did this vote come about?

Liberal Democrat MP Greg Mulholland, who proposed the reform, said it would "simply bring back market forces into a sector that frankly has become grotesquely anti-competitive".

He argues that the 400-year old tie system has been abused by the pub companies and that the basic deal - that a tied-pub tenant pays a lower rent to compensate for the higher beer price they pay - is no longer the case. Mr Mulholland claims that the average tied rent is now higher than the rent paid by non-tied tenants meaning, he says, that tied tenants are "being overcharged twice".

The new rules mean that a tied tenant of a large pub company, one which owns more than 500 pubs, would be able to have the amount of rent they pay independently assessed. This would happen when a rent review is due, or if there was a sudden change in circumstances, such as a rival pub opening nearby offering cheaper prices.

If they choose, the tied tenant could then instead choose a rent only agreement.

When did the pub companies become so powerful?

It was largely thanks to the so called Beer Orders, introduced in 1989.

The orders decreed no brewer could own more than 2,000 pubs and was aimed at enabling small brewers to survive in a market then dominated by six large national firms: Allied, Bass, Courage, Grand Metropolitan, Scottish & Newcastle and Whitbread.

However, the brewers, reluctant to open up their pubs to rival brewers' beers, instead created pub companies to which they sold their pubs. These pub companies were exempt from the Beer Orders legislation and as a result were able to own more pubs than the 2,000 originally decreed.

Will my pint be cheaper?

Hold your horses. This isn't actually law yet. The amendment to the bill still has to be voted through the House of Lords before it becomes law. Even Mr Mulholland, who put forward the amendment, has said in the short term it should be "business as usual" for pubs.

But if the change does become law, the jury's still out on the impact.

Campaigners backing the change have said if pubs pay less for their beer and rent then ultimately they will be able to charge their customers less: "Allowing over 13,000 pub tenants tied to the large pub companies the option of buying beer on the open market at competitive prices will help keep pubs open and ensure the cost of a pint to consumers remains affordable," says Tim Page, Camra's chief executive.

But analysts say it's quite possible the opposite will be the case: pub owners will find it hard to manage the costs of paying market-rate rents and as a result more pubs will close and there will be even less competition on prices.

"Whilst the larger managed units will be unaffected, life could become more difficult towards the bottom end of the market with a larger number of units deemed uneconomic by their current owners," said Langton Capital analyst Mark Brumby.

Mr Brumby warns that ultimately these pubs could end up being turned into convenience stores or residential homes.