How McDonald's conquered India

- Published

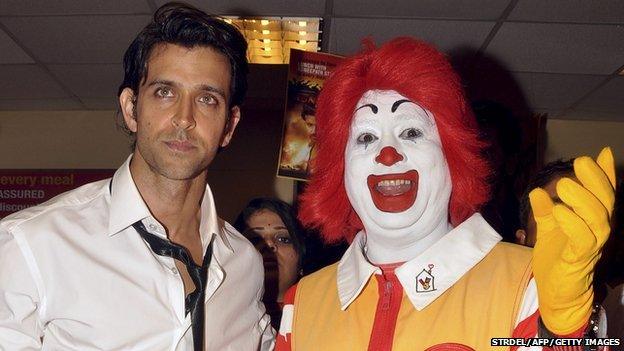

Bollywood star Hrithik Roshan poses with Ronald McDonald while promoting a film

A staunch vegetarian, Amit Jatia was 14 when he walked into a McDonald's for the first time.

It was in Japan and all he could have was a milkshake.

He loved it.

He is now the man behind McDonald's in India, responsible for the phenomenal growth the company has had in the country.

Vegetarian family values

When the American fast-food giant first contacted him in 1994 Amit's first challenge was close to home, convincing his vegetarian family to invest in the business.

"From my family's point of view we thought through this carefully," he tells the BBC.

"What convinced us was that McDonald's was willing to localise. They promised that there would be no beef or pork on the menu.

"Nearly half of Indians are vegetarian so choosing a vegetarian to run their outlets here makes sense."

Across the world the Big Mac beefburger is the company's signature product. Amit and his partners had to come up with their own signature product for India, so the Chicken Maharajah Mac was born.

Originally Amit was the local partner in the south and west of India, running the chain as a joint venture with the global McDonald's company.

Later he bought out the McDonald's stake and now solely runs the chain in the south and west of the country.

Changing the menu and dropping beef and pork was key to the success of McDonald's in India

Culture change

It hasn't been an easy journey.

"From a consumer point of view I had to start with the message that a burger is a meal," he says.

His research shows that in 2003, of 100 meals that people ate in a month, only three were eaten out.

They introduced a 20 rupees (20p) burger called Aloo Tikki Burger, a burger with a cutlet made of mashed potatoes, peas and flavoured with Indian spices.

"It's something you would find on Indian streets, it was essentially the McDonald's version of street food. The price and the taste together, the value we introduced, was a hit. It revolutionised the industry in India," he says.

Now eating out has gone up to 9-10 times per 100 meals and McDonald's in India has more than 320 million customers a year.

"Whether you love or hate McDonald's, they deliver a formula very well," says Edward Dixon, chief operating officer of Sannam S4, which provides market entry advice and support for multinationals in India, Brazil and China.

"Localised menu, delivered with precision quality at a price that works. One other trick they have used very effectively [is] an entry level ice cream which fuels the ability for consumers who might not ordinarily be able to afford to become a customer."

Young adults dominate the McDonald's restaurants in urban India

New markets, new customers

The kind of customers McDonald's attracts in India is very different from other countries.

There are still families with young children who frequent it. But diners also include many young people, aged between 19 and 30, with no kids.

During the week, Amit says, this crowd dominates the restaurants.

I wanted to see how true this was so I decided to have lunch in the McDonald's in Delhi's crowded Lajpat Nagar market area.

Sitting to my right, a young IT worker munches on a McSpicy Paneer while conducting a Skype meeting on his laptop.

On my left, a group of college students share a meal.

But what's most interesting are the two tables behind me.

One table has two elderly couples in serious discussion; the other has a coy-looking woman and man trying to have a conversation amidst the din.

With a bit of eavesdropping I find out that this is traditional matchmaking but in the modern Indian way.

The parents have introduced the potential bride and groom who are having their first official date under the watchful eyes of their mothers and fathers. The parents meanwhile are sorting out the details of the proposed marriage, all over a Maharaja Mac Meal.

So Amit's research seems to be right: unlike McDonald's around the world, there are hardly any parents with young children here.

Fast competition

McDonald's doesn't have the Indian fast-food market to itself:

Domino's Pizza has more than 500 restaurants across India

KFC has more than 300 restaurants

Dunkin Donuts has more than 30 outlets in India

Burger King has just opened its first restaurant in Delhi and other outlets are reported to be opening shortly - it too has dropped pork and beef from its menu

McLocalising

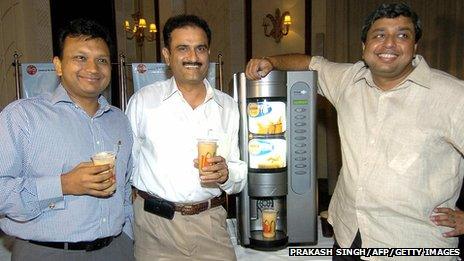

Amit Jatia (left) with Vikram Bashi and Sanjiv Guptam, the pioneers of McDonald's across India in 2004

Adapting McDonald's for the uniquely Indian market was a big expense when he started but Amit believes it has paid off in the long term.

When they started there was no lettuce supply chain in India. Most people used cabbage on burgers.

So they had to set it up from scratch.

The infrastructure is also now becoming a local venture.

"In 2001 we began to localise all the equipment that goes into the kitchen to build a burger," he says.

"For example, we took a burger and took it apart; now piece by piece every component is made locally.

More and more of the infrastructure in McDonald's in India is made locally

"All the kitchen fabrication is done locally. All the refrigeration, chillers and freezers and furniture are made locally."

In most cases their global suppliers have worked with local businesses to make that happen.

He wants to take it further. His current challenge is to make fryers locally.

While recent weakening of consumer spending has seen a slowdown in sales, overall Amit has managed to grow same-store sales by 200% and he says he's not done yet.

The plans are to open another 1,000 restaurants in the next decade.

"Think about it," he says, "India has 1.2 billion people and we have just 350 McDonald's [restaurants] to service them."

But India is not an easy market to work in, especially for multinational companies.

McDonald's in India has another partner in the north with whom they are still in the process of addressing the issue of ownership amid an ongoing legal battle.

So how did Amit Jhatia get around it?

"There are a lot of regulatory approvals needed to get something done," he says.

"But that is known. Once you know it, you factor it into your business plan."