Haile Gebrselassie: From athletics to the boardroom

- Published

Gebrselassie: 'I learnt to be more patient in business'

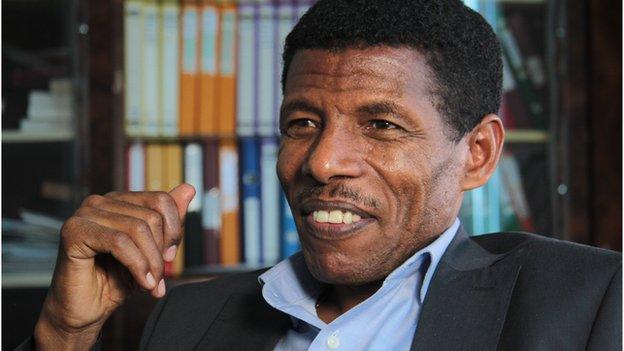

Haile Gebrselassie is the most famous man in Ethiopia. The double Olympic gold medallist and five-time world champion over 10,000m had a glittering athletics career and is now a successful and busy entrepreneur.

So when you manage to get an interview with him, you don't want to be late. Imagine our dismay then as we arrived at the Alem Building, affectionately named after Gebrselassie's wife, to be told that a power cut meant the lifts were not working and we had to lug our cameras and equipment up eight flights of stairs to the top of the complex.

Fortunately we got there before he did (he was also apparently delayed by the broken lifts).

When he does enter, wearing a charcoal grey suit and blue shirt, the 41-year-old smiles broadly and apologises for the power cut. He appears to be breathing normally, unaffected by the climb up the stairs.

He laughs it off and reminds us that he has lived most of his life in Addis Ababa, the highest city in Africa, and by now he's used to the high altitude and also the frequent power cuts.

The panoramic view from his office of the city and the nearby construction sites prompts a few questions about the investment choices he has made, which have turned him into a wealthy businessman.

He plays down the role of his property business though, saying it hasn't yielded high returns.

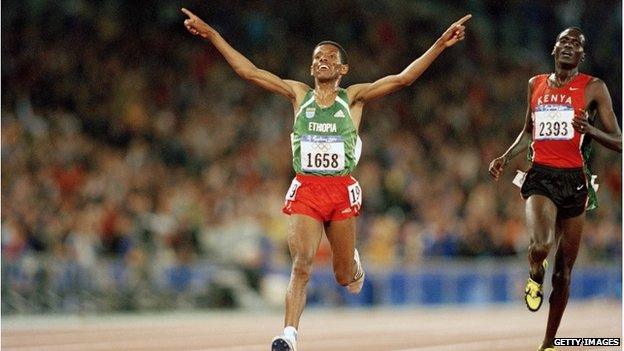

Gebrselassie set 27 world records and won Olympic gold in Sydney (pictured) and Atlanta

Using the winnings from his athletics career Gebrselassie first dabbled in real estate by building a multipurpose centre in Addis Ababa.

New ventures

However, he later chose to diversify his portfolio by buying land for a coffee plantation.

Coffee is the mainstay of the Ethiopian economy. It is the country's largest export commodity and more than 20 million smallholders are involved in the trade.

The sector is so lucrative that a commodity exchange was established a decade ago, through which farmers working in co-operative unions can sell to the New York market through facilitated deals.

For the "emperor of Ethiopian athletics", coffee farming is a fairly recent venture, but it has already proven to be a profitable investment.

"We have 1,500 hectares of land and we [used] 500 of that to plant full of coffee in two years," he says. "Now we export organic coffee to other countries."

But he goes on: "That's not enough, we in Ethiopia are rich in different resources." Which explains his latest endeavour into the mining arena.

However, with mining companies still prospecting for gold, it may be a while before anyone can assess the full potential of a new mining industry in Ethiopia.

Gebrselassie is the most famous man in Ethiopia, hailed as a sporting icon

'I believe in action'

Gebrselassie is obviously proud of his success in business, but he says people who assume that opportunities came easily to him because of his fame would be wrong.

Shaking his head, he refers to the earlier electricity cuts and says, "Me too, I am affected."

In addition, he says that he had to build the road leading to his coffee farm, because if he had waited for the government it may have taken five or six years.

Turning to athletics, I ask if it was hard to make the shift from the track to the boardroom. He admits that he needed to make some adjustments, especially because in business there is no instant success.

"I believe in action, running is action - running is just what you see... you win or not. In business you have to plan and wait."

He says his biggest challenge was working in a team and not being able to set personal goals. It's been a humbling experience for the man who followed up his success on the track by setting world records in the marathon.

"What I learnt is patience. A marathon is like two hours-plus of running. The 10,000m is less than 30 minutes. The same thing when I switch from running to business - I learn more patience."

Clear thinking

Although he has now swapped his running shorts for a dapper suit he still finds joy in running and plans to compete in a race for people over the age of 40.

Every day he jogs along the hills of Entoto, a mountainside town outside Addis Ababa. He says the morning air helps him think clearly.

Interestingly, there have been moments in his business career when his mind wasn't so clear.

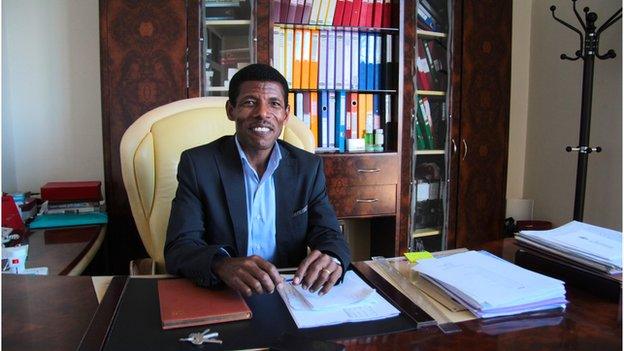

Gebrselassie wants new investors to come to Ethiopia

He recalls how 15 years ago, he decided to build the first ever cinema that would show locally made Ethiopian films, despite there being no local film industry.

His architect questioned the sanity of the project. Gebrselassie laughs heartily when he remembers how it all happened.

He found a freelance cameraman, commissioned him to write a script and after a few months an amateur film was made.

The first screening had five customers, the next had 10, later 15 and thereafter another film was made. Just like that the local movie industry was born in Addis Ababa.

He smirks and shrugs his shoulders, saying, "That's how one creates something."

Japanese philosophy

While the movie business entailed taking a risk, Gebrselassie is more measured when he considers what Africa needs to do in order to change the shape of local economies.

Staring out of the window, looking at a city that's rising from being a socialist-controlled economy into a free market, he makes a simple plea. "If you want to help Africa, don't bring money. Rather, bring good ideas."

With that thought, the athlete-turned-businessman excuses himself, late for a leadership seminar taking place down the road. It's a lesson about how to apply the Japanese kaizen philosophy in your business.

He believes the session will help him streamline his thinking, his business and ultimately the country.

He believes these are the lessons that will make Ethiopia function better as a frontier market that new investors are watching closely.