Are Scotland's new tax and spending powers fair?

- Published

- comments

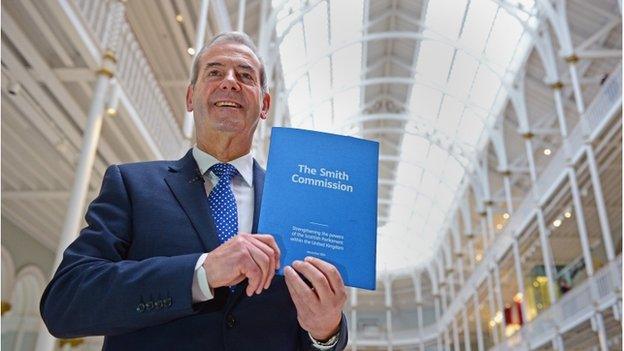

Lord Smith announced that the Scottish Parliament should have the power to set income tax rates and bands

The really important stuff on economic and fiscal devolution to Scotland is yet to be decided.

In saying that, you may think I've gone mad - given that the Smith Commission has apparently made some huge decisions.

Here is what stands out for me from today's announcement.

1) The Scottish parliament will have total control over income tax rates and the thresholds at which they kick in (but Westminster will still set the tax-free allowance).

2) Revenue raised from the first 10 percentage points of VAT on Scottish spending will be allotted to the Scottish government.

3) The Scottish parliament will have power both to create new benefits and vary some planned and existing benefits - including the housing cost element of Universal Credit, benefits for carers and the disabled, and cold weather related payments.

There are lots of other important new powers being transferred to Holyrood, including the ability to lower the voting age, change speed limits, license frackers, influence the new BBC Charter, and - possibly - change abortion rules.

But it is the transfer of big tax and spending powers that creates significant fiscal and economic uncertainties - whose resolution may have serious political consequences.

The lynchpin of all this is what the Commission calls the fiscal framework for the new devolution, which includes a number of principles.

Perhaps the most important is that at the precise moment that the new powers are devolved, Scotland's budget and the UK's budget should neither be bigger or smaller as a result of this transfer to Holyrood of new spending and taxing powers.

Or to put it another way, the block grant paid to Scotland under the Barnett formula should be reduced to account for taxes devolved to Scotland and increased to account for spending transferred to Scotland - and future payments under the new Barnett formula should be indexed to protect their real value.

Or to put it another way, neither Scots taxpayers or those in the rest of the UK should suffer detriment as a direct result of the new devolution.

Which is all very well to say, but my goodness it will be hard for Westminster and Holyrood to agree and implement.

The point is that income tax receipts and benefit payments vary considerably with the economic cycle. So determining at any point in time precisely what revenues and costs Holyrood is assuming will be pretty tricky.

And it is not just adjusting for the economic cycle that will be difficult.

Right now, for example, the British government's take from income tax is well below what it expected it would be, given the apparent buoyancy of the economy.

So what if the new grant formula was set on the basis of the current depressed income tax revenues, and then a few weeks later tax revenues suddenly and unexpectedly surged back to past trends?

If that were to happen the Scots would enjoy a terrific permanent windfall - and taxpayers in England, Wales and Northern Ireland would presumably feel pretty miffed.

Similarly the Smith Commission says Scotland should have new powers to borrow, because otherwise it could find itself running out of money in an economic downturn that reduced its tax revenues and increased its benefit payments.

But that opens quite a can of worms.

No Chancellor of the Exchequer would want to give a Scottish finance minister complete discretion to borrow, because it is almost impossible to conceive of how Scottish sovereign debt would not be guaranteed in theory or practice by Westminster: the chancellor would be terrified of what Holyrood would do it if had his credit card.

But setting rules for how much Holyrood can borrow will be very challenging. What is more, any uncertainty about what tax revenues are available to service either Scottish debt or whole-UK debt would presumably make investors more wary of buying the debt of either.

All of which may sound a bit technical and dull. But it boils down to something pretty simple and important - which is the perceived and actual fairness of the fiscal settlement for Scots and for those south of the border.

And right now it is impossible to judge whether the settlement is fair.