Deep sea salvage: Finding long lost treasures of the deep

- Published

Raiding Davy Jones's Locker: Gold coins brought up from the SS Republic by Odyssey Marine Exploration

Far beneath the ocean waves, nestling silently on cold dark sea beds around the world, lie the remains of about three million shipwrecks.

And that's a conservative estimate by Unesco (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), external.

They have fascinated generations of artists, writers, anthropologists and scientists.

Many mark the final resting place of their crew and passengers. Some are hundreds of years old, a time capsule from distant ways of life.

All are guardians of the treasures that sank along with them - be they in the form of uniquely preserved cultural heritage or cold hard cash.

Excavators of the Tudor ship the Mary Rose, external, which sank off the English coast in 1545, found 500 pairs of shoes among the 19,000 artefacts retrieved from the site, many of which are now on display.

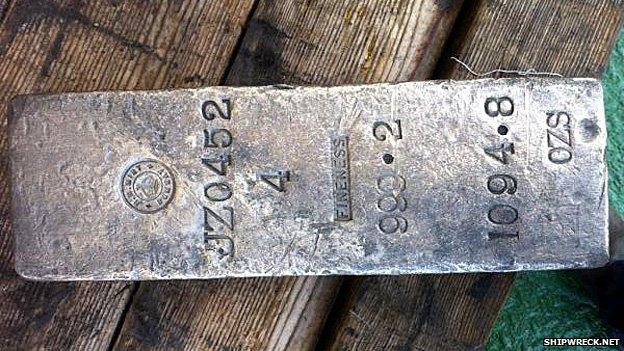

The SS Gairsoppa, external on the other hand, a steam ship sunk by a German U-boat off the Irish coast in 1941, went down with over 110 tonnes of silver on board.

In 2010 a US-based company called Odyssey Marine Exploration won a tender put out by the government to retrieve that silver from its resting place, 4,500m below sea level - one mile deeper than the Titanic.

Artefacts on display from the wreck of the Mary Rose

The Odyssey Explorer

Deep down

That sort of depth can only be reached by machine (the deepest recorded human scuba dive is currently 332m, according to Guinness World Records, external) and getting there is, to put it mildly, a technical challenge.

"Ten years ago you couldn't possibly have done it," Andrew Craig, senior project manager onboard Odyssey Marine vessel Explorer, told the BBC.

"It would have cost so much. Just getting a work class ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle) to 5,000m - they're just not built because there's so little requirement for them."

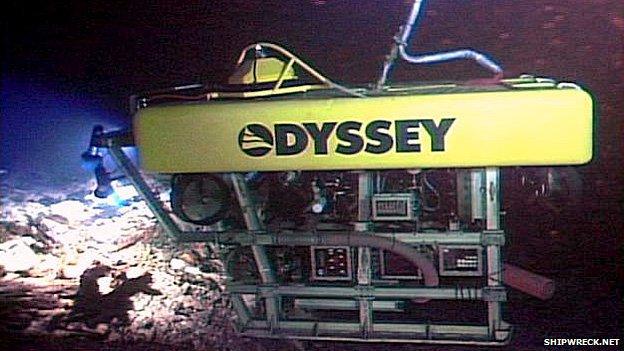

It took 3.5 hours for Explorer's onboard ROV, a 6.5-tonne vehicle named Zeus, to make each journey between the ship and the site of the wreck.

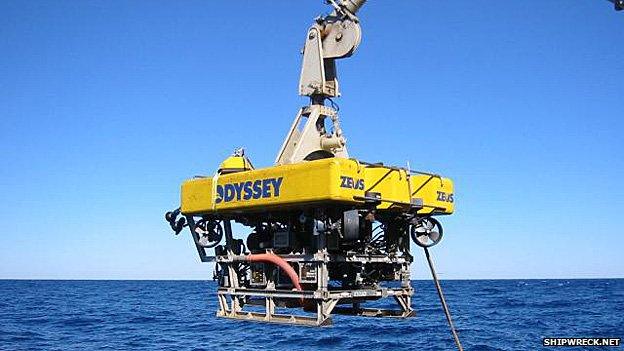

Odyssey's eight-tonne remotely operated vehicle (ROV), Zeus, is launched from the surface vessel, Odyssey Explorer, for descent to a deep-ocean shipwreck site

Zeus works at the rudder of the SS Republic shipwreck site, 1,700ft below the ocean surface

Zeus finds a porthole on the site of the SS Republic

With any sort of deep sea exploration, positioning is crucial. The proverbial needle in the haystack is much harder to find when it's floating in gallons of sea water, surrounded by marine life, and you can't use your fingers to feel for it.

"You want to know to within 10-15 cm where things are - and you need to be able to go back to them repeatedly," says Mr Craig.

In addition to Explorer's onboard sonar scanners and magnetometers (a kind of deep sea metal detector also used by the military to seek out submarines), Zeus has been equipped with an Inertial Navigation System.

This captures a range of data from numerous sensors, not only to navigate a path, but also to remember where it has been. It cost over £100,000 ($157,000; €126,000) and is just one of many sensors used by the team in guiding the ROV.

Better batteries

The technology advances still on Andrew Craig's wish list are surprisingly familiar.

The first is better wireless communication - ROVs still need to send data and receive instructions by fibre-optic cable, meaning they remain tethered to the ship.

The second is truly universal - better battery life.

"On our largest dive the ROV spent five and a half days on the bottom," he says.

"But we had to come up when the battery went on the beacon."

A ladder leading up onto the forecastle deck of the SS Gairsoppa shipwreck approximately 4,700m deep. One of the cargo holds can be seen on the left

The SS Gairsoppa had an emergency stern steering station on the top of the poop deck

A side-scan sonar image of the SS Gairsoppa

It's fair to say that deep sea shipwreck exploration is eye-wateringly expensive.

The cost of running a research ship such as the Explorer is about $35,000 (£22,000; €28,000) per day, including staff.

Those boats can get through five to 10 tonnes of fuel per day at $1,000 per tonne.

"You can be onboard for six months to a year to do a proper exploration," says Mr Craig. "You're into the millions very quickly."

Not surprisingly, funding is hard to obtain.

Odyssey Marine operates by keeping - and selling - a share of valuable hauls, while retaining items of cultural note and offering them up for display in museums. The firm kept 80% of the value of SS Gairsoppa's silver as part of its tender agreement.

"Odyssey Marine Exploration is very open about its business model," says Dr Sean Kingsley, founder of Wreck Watch and a company consultant.

"The concept ensures that unique cultural artefacts are permanently retained for museum display, while types of trade goods known by the thousands in museums across the world are considered for sale to cover expedition costs.

"Income is cycled back to pay for the expensive science: make no bones about it, deep sea wreck studies is by far the most expensive arena in archaeology," he adds.

Not everybody agrees with this commercialisation.

When Unesco drew up its Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage Convention, external in 2001 it specifically blocked what it called "commercial exploitation", and encouraged "in situ preservation" as its "preferred option" - permitting the removal of artefacts and the lifting of wrecks only for cultural rather than financial reasons.

Critics of the convention point out that iconic excavation projects like the raising of the Mary Rose would have been inconceivable under its rules, and just 44 of Unesco's 195 member states have ratified it to date.

Odyssey's Andrew Craig (right) on the deck of the Odyssey Explorer

A silver bar recovered from the wreck of the SS Gairsoppa

Recovering silver bullion from the SS Gairsoppa

Diving down

Of course, not all of the world's wrecks are overwhelmingly inaccessible.

It is not uncommon for amateur scuba divers and even beach walkers to also find themselves in possession of shipwreck bounty.

In the UK, a government official called the Receiver of Wreck, external is responsible for identifying and trying to trace the ownership of any artefacts from the seabed in UK waters - or brought into the country from elsewhere.

In 2013 the department received more than 300 reports detailing more than 36,000 found items - and the majority came from recreational divers, deputy receiver Beccy Austin told the BBC.

The most commonly reported artefacts include portholes, fixtures and fittings, navigational equipment, and ship bells, she says.

The department has one year to attempt to establish ownership.

"The law says the onus is on the owner to prove ownership, but lots of owners don't realise they are the owners," says Ms Austin.

"Reaction is varied - some are really interested, others see their wreck as a liability."

A number of 19th Century ceramic transfer print soap dishes handed to the Receiver of Wreck

A United East India Company bronze cannon dated 1807. The number four was used to ward off evil

Often those owners will be government defence ministries or insurance companies.

Many simply allow the finder to keep their find, although they have no legal right to do so, she adds.

Astonishingly, about 60% of finds are traced to their rightful owner, but if the investigation fails, the artefact becomes the property of the Crown.

Either way, the finder is entitled to a salvage award, which is negotiated by the finder and owner - a fair combination of a percentage of the market value plus the effort gone to by the salver. It can be up to 90%.

The Crown, however, does not pay the award - the Receiver will generally try to find a suitable museum for the artefact.

Sometimes ancient material can find a surprising new lease of life once it is back on land.

In 2010 Italy's National Institute of Nuclear Physics used 120 ingots of lead, retrieved from a Roman shipwreck, to conduct a major investigation into neutrinos.

The ancient lead was useful because it had lost all its radioactivity - but Donatella Salvi, an archaeologist at the National Archaeological Museum in Cagliari where it had been kept, admitted to the science journal Nature that handing the ingots over was "painful", external.