Taking stock: Tech to thwart retail's worst miscreants

- Published

Rebecca Minkoff is a very busy woman. And like all successful fashion designers she likes to be at least a few steps ahead of the rest of us.

So it's not surprising her first flagship store - in the heart of Soho, New York City - is a cleverly concealed mix of bricks and bandwidth.

A partnership with eBay means that shoppers can log on in the shop via a giant interactive screen, to make a wish list of items.

Once in the changing room, the shopper can also communicate digitally with tablet-carrying sales associates, who then bring over requested clothes in different sizes and colours.

Once a decision has been made the guest can then pay for merchandise without ever standing in a queue or seeing a cash register.

Rebecca loves the idea of providing her customers with a physical shopping experience that brings with it all the best bits from an online world that her younger customers crave.

But as it turns out her new way of doing business might also help solve a major problem that plagues a lot of high street business owners - theft.

The high tech fitting rooms serving clients at Rebecca Minkoff's New York boutique

Sales assistants can check stock status from their tablets while on the shop floor

Tag it

To enable the customer care aspect of her boutique, every item has an RFID (radio frequency identification) chip embedded in the price tag.

So the in-store system can track the location of every shoe, skirt and handbag within the four walls, including the row of changing rooms which have been painted with a special surface to prevent radio signals becoming cross contaminated.

Of course, currently anyone can decapitate a tag in seconds, but Ms Minkoff says the shop is just one step away from a foolproof method of preventing "shrinkage", as the loss of products is known in retailing.

"Today, they could [walk out of the door with the item] because there is a [removable] tag on this, but our next goal once a back end issue is solved, is embedding them in the clothes, bags and shoes and it will become a security device," she says.

Each price tag has an RFID tag embedded in it, making the items easy to track

Rebecca Minkoff in her New York shop

Another problem in the fashion world and retailing as a whole is fraudulent returns.

Only 1% of shoppers do it, but it added up to $16.3bn in the US alone in 2013 according to the National Retail Federation (NRF). And it's getting worse.

One trick known as "wardrobing", played out countless times especially around this time of year, is to buy a cocktail dress, wear it once, look absolutely stunning for a couple of hours, then return it the next day.

So now lots of shops put the tag in a prominent position on the garment that's super inconvenient for anyone to hide when taking the dress to a one-and-done style event.

Managers are also getting stricter about their return policies. Accidentally rip the tag off or lose the receipt? Too bad.

We are watching

That of course is a pretty low tech solution.

That's where The Retail Equation (TRE) comes in.

It is not an organisation that US shoppers know much about, except maybe "returnaholics", and its clients are kept top secret.

But the way it works is that a network of shops share information about people who mimic the behaviour of "serial returners".

These are people who may, for example, buy a top-of-the-line TV just before the Superbowl and keep it for less than 24 hours every year.

Buying a high-end TV the day before the Superbowl and returning within 24 hours is seen as suspicious

The information collected from individuals may vary from state to state, and the return policies differ from shop to shop, so a sophisticated algorithm is needed to identify possible abuses.

Tom Rittman, vice president of marketing for The Retail Equation, points out that a refused return is therefore an objective result made by a computer, allowing even the most subjective cashier to be removed from the decision making process.

"The factors that Verify-3 (the name of the system) may use for a given retailer include the frequency of returns, return dollar amounts, whether the return is receipted or non-receipted and purchase history," he says.

"Verify does not use other factors in authorising returns such as age, gender, race, nationality, physical characteristics or marital status."

Faking it

Another enterprise where a complete crackdown has long seemed elusive is the art of counterfeiting.

But in a few years it's possible that many products, especially high end ones, will feature a logo or pattern created using nanotechnology.

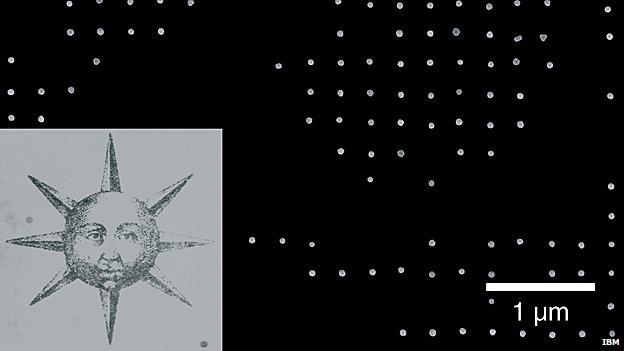

The particles that make up the patterns are held in place by the surface tension of water

The images are made up of thousands and thousands of tiny dots

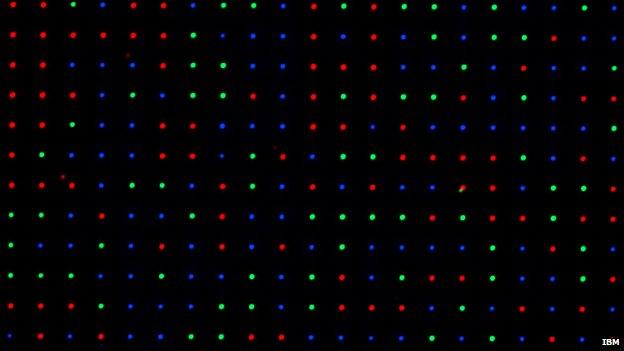

Fluorescent spheres which give out red, blue and green light can also be used to create patterns

The result is impossible to see with the naked eye, as it's a tiny fraction of the size of a pin head.

The logo or design is stamped onto a surface such as paper, glass, metal or precious stones in such a way that particles are held in place by the natural surface tension of water.

Dr Heiko Wolf at IBM Research in Zurich

Fluorescent spheres which give out red, blue and green light can also be used to create patterns.

Dr Heiko Wolf, a physicist at IBM Research in Zurich, claims it would be daunting for even the cleverest counterfeiter to replicate the technology.

That pleases many high end manufacturers, who are constantly on the look out for ways to hold on to their intellectual property.

"Yes, several have been in touch, in most cases they need the technique to print faster, which requires more research and investment," he says.

"The other challenge for them is how they can read the nano patterns at a retail location or at customs controls, so they would need to invest in optical detection instruments."

Some companies have high hopes for the technology after seeing 3D holograms and an endless array of other anti counterfeit measures beaten over time.