Retail robots: The droid at till number 7

- Published

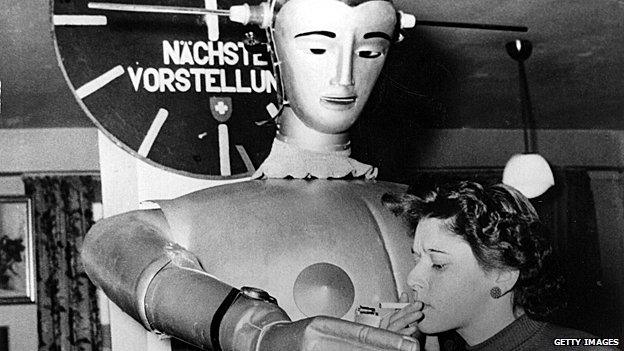

Are you being served? This robot in a German department store in 1955 could light cigarettes and answer questions in different languages. His descendents are a bit more hands on, and are probably anti-smoking

A hardware store in San Jose has a new star employee. It can speak English and Spanish, recognise any part at sight, and knows what the shop has in stock on a second by second basis.

And it's also a robot.

OSHbot, as it is called, measures roughly 5ft, and boasts a 3D scanner and touchscreen.

"It's not just robots for robots' sake, or a marketing gimmick," insists Kyl Nel, executive director of Lowe's Innovation Labs.

Lowe's is an American DIY chain, and the robot's ultimate employer.

A store associate, no matter how talented, couldn't know the real-time location and current stock levels of all of a shop's wares, according to Mr Nel.

The OSHbot is on the shop floor at the Lowes in San Jose

The robot can scan a screw and match it to the correct size and type in store

The 3D scanner connects with a database of thousands of small screws and hinges.

Typical customers entering the store with a small part, he says, "don't know what it's called - all they know is they need 20 of them."

Much of this could be done with a smartphone, although the scanner is more powerful than a mobile phone camera.

But it is more natural to have someone to ask.

"It's another barrier if you have to download something. If you come into a store you're there for a reason, and you typically want it right away," Mr Nel says.

At the moment there are only two of the robots, with variations being field tested.

This includes whether the robots' voices should be male or female, electronic or human; whether they should have a face or not; and how fast they should move.

"But we didn't go to all that trouble to do one store in the Bay area," adds Mr Nel.

The plan is to roll the robots out to other locations once field testing is over

Plays well with others

OSHbot is "a great example of where robotics are today in terms of their usefulness," says Rob Nail, chief executive of Singularity University, located in Nasa's Silicon Valley research park.

They are built to perform very specific, fairly limited tasks.

The key to a robot-to-human interface is that it is embodied, suggests Philip Solis, a robotics expert at ABI Research. "You're moving towards something you can interact with more - you can ask it information, and it can respond to you."

As an example he points to Jibo, which is being developed by MIT professor Cynthia Breazeal, and billed as the "world's first family robot".

Jibo does not move around, but can swivel, answer questions, read stories, and take group photographs.

"It's another form of user interface to the internet," says Mr Solis.

Human interaction is likely to prove the most difficult thing to do well, argues Mr Nail, "since we haven't had a lot of robots interacting with consumers."

Jibo - with its creator, MIT professor Cynthia Breazeal, is billed as the world's first family robot

OSHbot costs roughly $150,000 (£95,319, €120,200), Mr Solis estimates, though this unit cost would decrease as the market matures. By contrast, Jibo will enter the marketplace at the end of 2015 for $499 (£317, €400).

Robotics components are becoming cheaper, and instead of the full onboard computer previously required to provide processing speed, personal robots now "really just need smartphone guts", says Mr Solis.

The cost of robotics has moved from accessible only to big business, to affordable for small enterprise, meaning much more experimentation will take place, says Andra Keay, head of Silicon Valley Robotics, a non-profit industry group.

She predicts gradual improvements to things we already have based on robotics technology.

Help with the heavy lifting

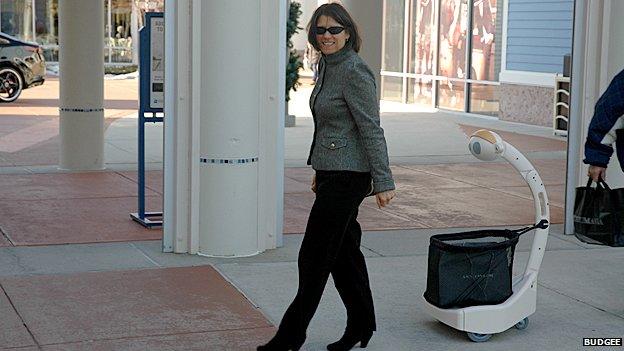

In this way Budgee, a robotic shopping trolley developed by Five Elements Robotics, might just become what we expect every shopping trolley to do.

This robot is purely functional. Rather than replicating a human shop assistant, it follows shoppers with their goods in tow - particularly helpful for the elderly or those with limited mobility.

Budgee is a robot shopping trolley - you can buy your own from March 2015

Budgee folds up so it can be stowed in a car boot

This is not a cunningly-disguised Dalek. It's a robot security guard from Knightscope

On similar lines are the K5 and K10 robotic security guards being field tested by Knightscope - and in passing, possibly resembling a Dalek.

They use similar technology to the Google self-driving car, can read 300 vehicle registration plates a minute, and summon police or security guards when they encounter evidence of intruders.

Much of the biggest retail impact of robotics technologies will in fact be out of customers' eye.

Amazon purchased Kiva Systems - which makes warehouse robots - in March 2012 for $775 million (£493 million, €620 million), and is using them in its warehouses. They're not alone - robotic pickers and packers are becoming a common sight in retail distribution centres.

It's a very different approach to that of Aldebaran Robotics. Their humanoid Pepper robot was created for Japanese company Softbank, and it's more like the robot companions of science fiction.

Pepper is designed to recognise human emotions, and to react to its environment based on information held in a continually evolving cloud database. It will go on sale in Japan in February 2015 for ¥198,000 ($1,900, £1,064, €1,434).

Miss Keay thinks this is a difficult price point for its makers to pull off.

"When we're going for robots that are cheaper than $20,000-$50,000 (£12,700-31,777, €16,000-40,050), you're going to have a lot of tradeoffs in either durability, size, or functionality."

Earn your crust: Pepper the robot puts in his 9-5 at a Tokyo electrics shop, selling Nestle coffee machines

Pepper gives this Japanese shopper the hard sell

This is droid you're looking for

How a robot looks could guide how we interact with technology in coming years.

"A voice in a headset saying turn left, now turn right feels a little too intimate, I think," says Mr Nail.

"But," he adds, "it's not going to be humanoid, really it's not - when people try to make them look too human, it kind of creeps us out."

We're more likely to see robots like Jibo at the moment, thinks Miss Keay.

R2D2 doesn't need to worry about what to do in the downtime between Star Wars sequels - a Saturday job in Budgens beckons

"You've basically taken out all the hardware problems, and made a physically embodied social interaction in a not very difficult piece of hardware," she says,

"Whereas producing a small humanoid that was affordable, it's just a little too complex for where we're at."

"I really hope the novelty of the robot wears off quickly," says Singularity University's Rob Nail.

He thinks robots with access to customer databases could recreate a time "when the shopkeeper would know your name and preferences, and you'd have a tab with him."

In other words, rather than the sterile high tech environment often seen in science fiction, robots on the shop floor could bring back the personal service while shopping we associate more with the past, than the future.