Abenomics is put to the vote

- Published

- comments

The question for Japanese voters is how many options are there to deal with such deep-rooted economic problems?

Two years after Prime Minister Shinzo Abe took office and announced bold reforms dubbed Abenomics to revive the economy, the Ishikawa Casting and Machining factory hasn't seen the benefits.

Located in Tokyo, it's a family business run by Yushiaki Ishikawa who took it over from his father. He told me that small and medium-sized businesses like his are having a hard time.

"We don't feel that we're benefitting from Abenomics at all. We don't even see its shadow or hear the footsteps of Abenomics. We do have some hope, but right now, there is nothing."

The Ishikawa Casting and Machining factory has yet to see the benefits of Abenomics

He raised wages for his workers last year, because he believed in Prime Minister Abe's plan.

He sold his car to finance his company, as business has struggled since the economy tipped into its third recession in four years. So, unless things turn around fast, he can only keep the company going for another year.

In the spring, before the recession that started in April, wages rose by more than 2% for big companies. They were raised, on average, for smaller ones too, albeit less.

Defeating deflation

But, will employers continue to do so if the economy doesn't turn around? And sustained wage rises are required for price increases to take hold as Japan is still battling to defeat 15 years of deflation, though with some recent promising signs.

Those are what Abe has been touting on the campaign trail as he faces a general election this weekend. It's an early election that he called to seek a renewed mandate.

Abe said that his economic policy is to increase employment and raise wages. In the two years since Abenomics started, he says that over a million new jobs have been created.

But, for Japan, it's the dual challenge of being the fastest ageing economy in the world and defeating deflation that's the hard combination. And they're not alone.

In the demography sense, developed countries are becoming Japanese. Already, Germany and Italy are not far behind in terms of their ageing profiles and also face the threat of deflation.

But, Japan is in the lead. It's the fastest ageing country in the world, whose population has been shrinking for a decade.

Robotics

Abenomics has been trying to address that depletion of productive capacity in the economy. One of Abe's initiatives is to advocate adding women to the workforce to match the participation of men, which could increase GDP by some 15%.

What about robots? Japan is investing heavily in robotics and artificial intelligence. Robots can now do more than repetitive tasks like assemble cars, such as interacting with humans.

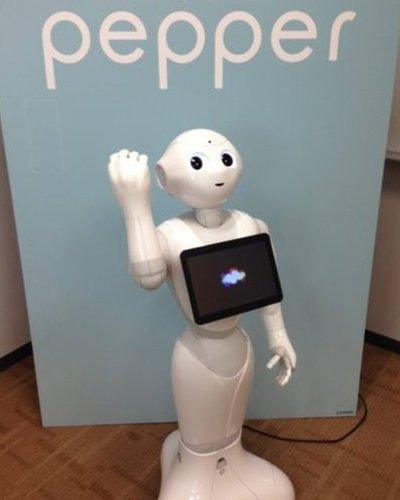

Pepper can read emotions and fill you in on the latest news

I met a robot called Pepper who can read emotions and tell me the latest news. That is, once he understood my Japanese accent.

It won't be Pepper who can add to Japan's productivity as he's designed for communication. But, a future version could potentially do work that is now done by humans. It won't be the entire answer to revive productivity as Japan ages, but robots and robotics could help.

Certainly, a lot more work is needed to turn around Japan's economy after two decades of stagnation.

Japan's voters will decide this weekend if they will give Abe another shot to do so. The indications are that he will win another large majority with his coalition partner.

The question that will remain is whether another four years will be enough time to at least set in motion the policies that could address such deep-rooted structural challenges.

The answer will matter for all of us.