'Mr Market' and Me

- Published

- comments

It is not often I am attacked by an Oxford economics professor and a Nobel-prize-winning economist, but I have been - by Simon Wren-Lewis and Paul Krugman - for this blog on the chancellor's autumn statement of two weeks ago.

Here is Wren-Lewis's critique, external and here is Krugman's, external.

What they hate is my fey anthropomorphism of the financial markets as Mr Market, and my reporting of what investors have told me - namely that George Osborne's record as a deficit-cutting chancellor may be worth something in terms of the interest rate the government would pay to borrow after the election.

Here is what I wrote:

"Mr Market matters because he decides what price the government pays to borrow, and whether the government will continue to benefit from the current record low interest rates.

"The Tory view is that those interest rates can only be locked in if the government continues in remorseless fashion to shrink the state and net debt.

"What Labour would point out is that countries in a bit of a fiscal and economic mess and currently refusing to wear the hair shirt that the European Commission thinks necessary, such as Italy and France, are also borrowing remarkably cheaply.

"And here is where Mr Market may be capricious, according to my pals in the bond market.

"They say the UK's creditors would probably be forgiving and tolerant of George Osborne borrowing more than he currently says he wishes to do, in that his record of reducing Whitehall spending by £35bn since taking office in 2010 has earned him his austerity proficiency badge.

Ed Balls - something to prove to investors?

"But Ed Balls has never been chancellor, although he was the power behind Gordon Brown when he ran the Treasury and much of the country, both in the lean years from 1997 to 2000 and the big spending Labour years thereafter.

"So Mr Balls has yet to prove, investors say, that he can shrink as well as grow the apparatus of the state."

Now there are a few things to point out, before we move on to the interesting economics about all this.

The first is that Wren-Lewis and Krugman know vastly more about economics than me. As I am sure you have noticed, I never describe myself as an economist, but always as a journalist who happens to be very interested in economics.

Journalism is my stock-in-trade. And as a journalist, it is my duty both to report what relevant people are saying to me, such as participants in the bond market, and to be - as far as possible - balanced and impartial.

Even in the passage which they hate, I highlight that the experience of France and Italy - in being able to borrow remarkably cheaply in spite of being perceived to be mismanaging their national finances - somewhat undermines the idea that governments are awarded a bond-market premium for being good at austerity (as it were).

So in my view, my column is the beginning of a debate about what the election of a Tory or Labour governments would respectively mean for the borrowing costs of the UK, not the end of one.

And here is where it gets interesting.

The argument of Wren-Lewis and Krugman is that unless there is a serious risk of a country becoming insolvent, what its government pays to borrow is more correlated with its growth prospects than with the size of its public-sector deficit.

So at different times since 2010, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy all paid penal and existentially threatening rates of interest - because of fears they would be unable to keep up the payments on their debts (fears that, of course, became self-reinforcing).

The UK has avoided that painful and expensive fate. Why? Well partly because it has an independent central bank, the Bank of England, able to set interest rates and create money to suit the precise needs of the UK - in the way that the European Central Bank, with its pan-eurozone responsibilities and restrictions on its money-creation powers, was unable to do.

But does that mean a plan to reduce the deficit has been irrelevant to the borrowing costs paid by the HM Treasury? That seems implausible.

The government inherited a deficit (a gap between what it spends and what it raises in taxes) of 10% of national income or GDP. Wren-Lewis and Krugman would presumably agree that a 10% deficit is unsustainably high - and if it recurred for years would prompt fears for the UK's solvency.

So getting the deficit down from 10% - or perhaps promising to get it down - must have had some bearing on the so-called risk premium for lending to the UK government, or the interest rate that the UK had to pay to borrow.

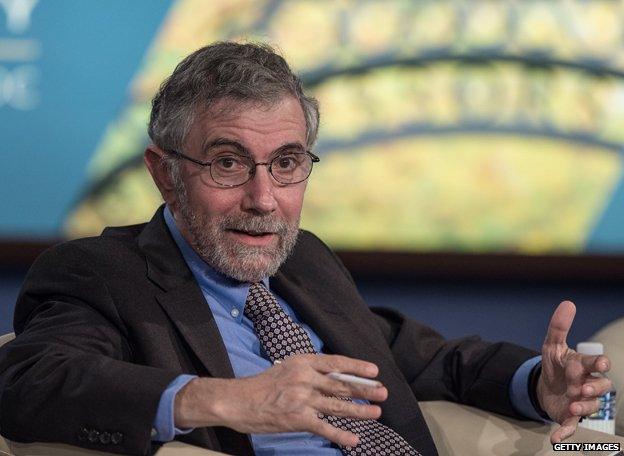

Paul Krugman

That said, what Krugman and Wren-Lewis would argue is that after the solvency risk had been eliminated - and perhaps it was pretty quickly for a UK with a stable political system and with a government and opposition both committed to reducing the deficit, albeit at different speeds - what mattered at that point was growth prospects for the UK.

Their view is that the government's austerity is what has caused interest rates to be so low, not because it impressed investors, but because it made growth prospects for the UK materially worse.

They would argue that government spending cuts were responsible for the long years of economic stagnation. And that investors therefore chose to invest in allegedly safe government bonds, driving down the interest rate paid by the government, rather than taking greater risks by putting their money into shares and other investments whose returns are more dependent on growth.

And, of course, if growth was stronger, the Bank of England would itself have bought fewer bonds through its quantitative easing programme, and might even have put up its own policy interest rate.

So for Krugman and Wren-Lewis, austerity is indeed responsible for interest rates being low - but because it is a growth-wrecking policy, rather than a sensible way to reduce the deficit.

As it happens, in practice there has been much less austerity than the chancellor promised and Messrs Krugman and Wren-Lewis feared. The deficit has only halved since 2010, rather than being eliminated as George Osborne promised.

And one reason why the deficit is still big and with us is that economic stagnation triggered the economic stabilisers. Benefit and pension payments have been greater than George Osborne hoped and wanted, because people's earnings have been so weak.

What's striking is that bond-market investors haven't punished Osborne for being less austere than he pledged. The UK continued to borrow at record low interest rates.

So perhaps Krugman and Wren-Lewis are right that greater austerity isn't closely correlated with cheap funding costs for the government. And perhaps Osborne in practice is closer to their position on all this than he would admit.

But there is another phenomenon which perhaps challenges Krugman's and Wren-Lewis's passionately held view.

The UK is currently the fastest growing rich, developed economy in the world - and over the past year its growth prospects for the coming few years have been revised up significantly. So the question is why, in those circumstances, interest rates for the UK government have fallen even more during 2014, if - as Wren-Lewis and Krugman say - those rates should reflect future growth prospects.

I've written a good deal about this, as you know. Borrowing costs for the UK government are currently the lowest on record, especially for long-term debt, lower even than at the tail end of the Great Depression in the 1930s.

Depression-era London, 1930s - UK government borrowing costs are now comparably low

One fashionable explanation is that investors are looking through our economic revival to decades of sub-par performance. It is the argument that developed economies like Britain's face "secular stagnation".

But we can't be certain that is what's happening. Even most proponents of secular stagnation admit that we are in the territory of surmise here rather than scientific rigour.

Even so, it is plausible that the UK won't be punished with higher interest if it elects a Labour government that would reduce annual government spending by £50bn less than the a Tory government would do by 2020.

Or rather, on the Krugman and Wren-Lewis view of things, if interest rates were to raise relatively faster with a Labour government, that would be because the UK's growth prospects would be enhanced by a diminution of austerity.

And here of course is where it gets messy - because how could we ever know for sure why interest rates were higher?

That said, even if they were right that rising rates were a sign of a good thing about Britain, namely accelerating growth and improving prosperity, that's not the end of the debate.

Why not?

Well don't forget that the UK current has public sector debt of more than £1.4tn and that debt is rising at an annual rate of more than £90bn. So even if interest rates for the government were to rise for the right reasons, its debts would be higher in absolute terms under Labour and the UK government would end up paying more in interest - which would be money not available to pay for health and education.

Labour would argue that its debts might be higher in absolute terms in the short term, but that as a proportion of the economy they would be lower at some point - and would therefore be more affordable - because growth would be faster.

Now to be clear, there are economists who attack the idea that the deficit and debt can be cut by growing the economy with all the vehemence of Krugman's and Wren-Lewis's lampooning of me and Mr Market. This will be the big punch-up, for economists, of the general election campaign.