Whatever happened to the future?

- Published

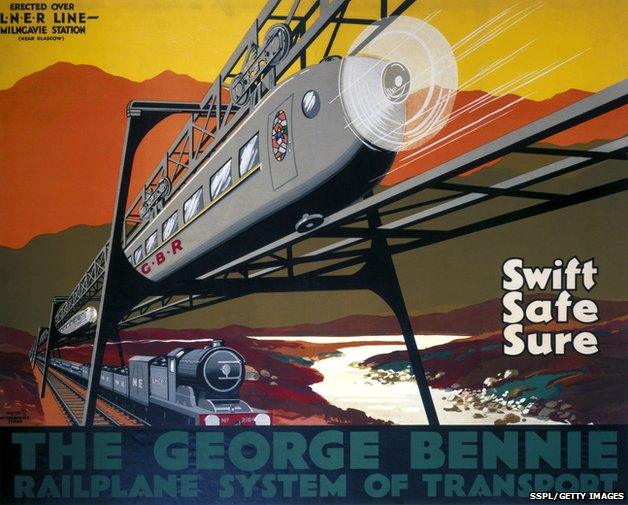

George Bennie's 1930 Railplane failed to attract backers...

Whatever happened to interplanetary travel, hover cars, and hypersonic jets?

Once it seemed as if there were no limits to how far or fast we could travel, such were the leaps in technological development in the 19th and 20th Centuries.

Inventors dreamed up all sorts wonderful vehicles, from rocket-propelled bicycles to flying cars, propeller-powered railways to monowheels.

In 1895, HG Wells even imagined a machine that could travel through time.

Steam power, the internal combustion engine and flight promised unprecedented levels of mobility and freedom.

Nation competed with nation to travel further, higher and faster by land, sea and air.

Speed was king.

Richter's 1931 rocket-propelled bicycle was never likely to gain mass appeal...

Is it a car or a plane? An AH Russell flying car concept from 1924

Nuclear dreams

And when the nuclear age dawned it seemed as if we had another, almost limitless power supply at our disposal, prompting thrilling designs for nuclear-powered rockets, cars, planes, trains and boats.

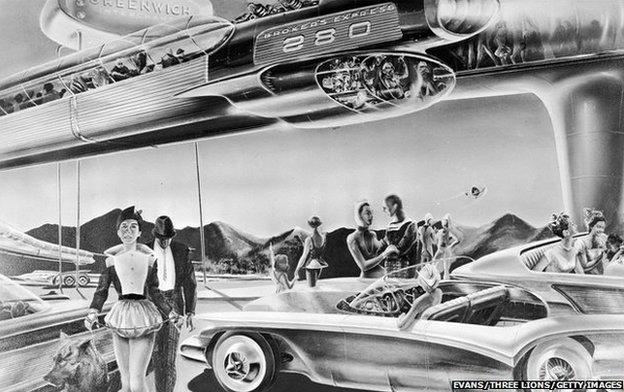

"On that train all graphite and glitter; undersea by rail; 90 minutes from New York to Paris... What a beautiful world this will be, what a glorious time to be free."

So sang Donald Fagen in the song I.G.Y. [International Geophysical Year] from his 1982 album, The Nightfly, evoking the technological optimism of his childhood in 1950s America.

In 1957, the year the song is set, the USSR launched the world's first earth-orbiting satellite, Sputnik 1.

A 1950s vision of what future commuting might look like

The 1952 Couzinet Aerodyne RC-360 "flying saucer" failed to get government backing and never flew

The 1960s TV programme Thunderbirds continued the idea that technology would help us master gravity

Mankind seemed to be one step away from becoming Masters of the Universe.

"People were looking at the pace of technological development and as we got into quantum physics it even seemed that the notion of teleportation was plausible," says Glenn Lyons, professor of transport and society at the University of the West of England.

"There were certainly some leaps of faith."

Commercial reality

So why did so many of those wide-eyed visions for tomorrow's transport never come to pass?

"The reason they didn't happen is the same reason why they won't happen in the future - technological utopianism," says Colin Divall, professor of railway studies at York University.

Concorde, the Franco-British supersonic passenger jet was noisy, polluting and expensive

"There's always a vested interested in overhyping new transport schemes, because inventors are looking for investment."

And there's the rub - money, or lack of it.

George Bennie's Railplane - a suspended carriage driven by propellers fore and aft - made it to the prototype stage near Glasgow in 1930, but did not then get commercial backing. Bennie went bust in 1937.

"Bennie's train did work as did other prototypes, such as the hovercraft on a track in the late 1960s, but they were never commercially viable," says Prof Divall.

The Railplane failed to attract backers and never made it beyond the trial stage - Bennie went bust in 1937

Rene Couzinet's elegant and intriguing Aerodyne RC-360 "flying saucer" failed to win government support and never got off the ground - literally.

Concorde, the elegant delta-winged supersonic passenger jet capable of 1,350mph (2,173kph), was noisy, polluting and pricey. It made its last flight in 2003.

Space travel in particular has proved astronomically expensive - pun intended - which is why no-one has revisited the Moon since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972.

Nasa's 1972-2011 space shuttle programme cost nearly $200bn (£132bn) in total for 135 missions - or about $1.5bn per flight.

Gravity, it seems, is a very tough nut to crack.

Tomorrow's Transport is a series exploring innovation in all forms of mobility against a backdrop of global warming and rising population.

Alan Bond, founding director of Oxfordshire-based Reaction Engines, believes his company has developed a jet engine capable of powering a passenger plane at Mach 5 - five times the speed of sound - meaning a flight from London to Sydney would take under five hours.

"But at the moment no-one has moved on that because it's going to be very expensive to develop - there has to be a strong commercial incentive," he says.

Innovation costs, and if the invention doesn't solve a pressing problem for the majority of people at a price they can afford, it's unlikely to take off.

Why don't we see electrically powered perambulators (1923) on our streets?

Crash and burn

It also doesn't help if your futuristic transport project ends up killing people.

The sinking of the "unsinkable" Titanic in 1912, with the loss of more than 1,500 lives, did little to increase the popularity of luxury ocean liners.

But it did usher in a number of new maritime safety regulations and ultimately did little to halt the mid-20th Century boom in ocean travel.

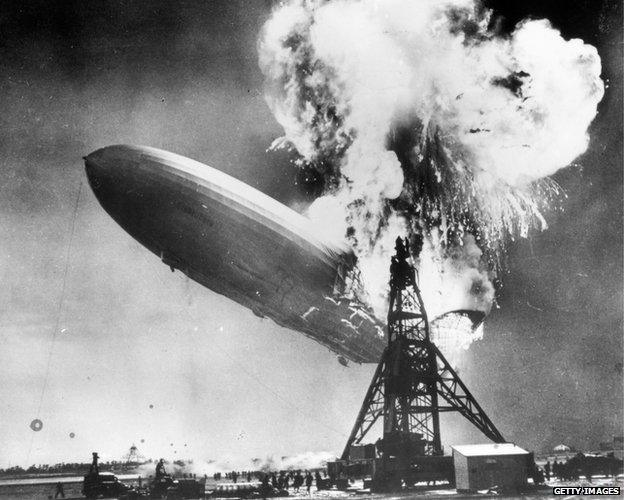

The Hindenburg zeppelin disaster in 1937 led to the end of airships as passenger transport

However, when the majestic Hindenburg, the largest hydrogen-filled zeppelin ever made, caught fire and crashed to the ground in 1937, killing 36 people, the disaster effectively ended the use of airships as passenger transport.

Air travel in particular demanded stringent global safety standards to win public trust, leading to a conservatism in design and a cautious, iterative approach to technological development.

The iconic Boeing 747 "Jumbo Jet", first flown commercially in 1970, looks almost identical to the 747s flying today, 45 years later.

Similarly, motor cars of the early 20th Century were more distinctive and diverse than they are now, but the need for global safety standards saw a gradual homogenisation in design.

The Volkswagen Beetle hasn't changed its shape much in over 70 years

Low carbon future?

Of course, global warming caused by manmade greenhouse gases has imposed severe strictures on all future transport projects.

Transport contributes about 25% of global carbon dioxide emissions, yet the global population continues to rise along with demand for mobility.

Car technology may have come on in leaps and bounds, but our potholed roads are gridlocked and many megacities around the world are wreathed in lethal pollution.

Our wantonness with hydrocarbons has become self-destructive and cannot continue, argue many.

So the race is on to switch to alternative low-carbon fuels - conventional electric batteries, hydrogen fuel cells, and compressed air to name a few.

There is also a lot of work going on to make our existing vehicles more efficient - using more lightweight materials, for example - and making use of data analytics to improve how we operate and integrate our urban transport systems.

Will electrically powered driverless cars change our attitudes to urban transport?

But in the digital age, are we beginning to think differently about transport?

"Our cities will increasingly function through the mass movement of information rather than the movement of vehicles," argues Prof Lyons.

Others disagree, believing the human need to travel, explore and trade will always keep us on the move.

Over the coming weeks our Tomorrow's Transport series will be exploring how we are responding to these challenges and featuring forthcoming innovations in planes, trains and automobiles.