Tennis racquet technology comes with strings attached

- Published

The BBC's Dave Lee looks at developments in tennis technology

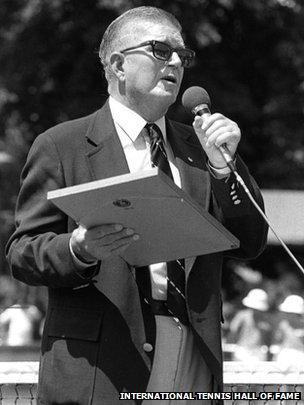

When it came to technology, William Hester was a pretty relaxed kind of guy.

The man known affectionately as Slew was asked in the late 1970s about the changes in the equipment used to play tennis. He didn't hesitate.

"You can play with a tomato can on a broomstick if you think you can win with it," he declared.

As the then-chairman of the US Tennis Association, his opinion mattered greatly.

But oh, how times have changed.

Hester died in 1993, aged 80. During his lifetime he saw a game that evolved immensely.

Wooden racquets became steel. Steel became carbon. Carbon will - sooner rather than later - become graphene.

Now the technology used when creating tennis racquets is taken very seriously indeed.

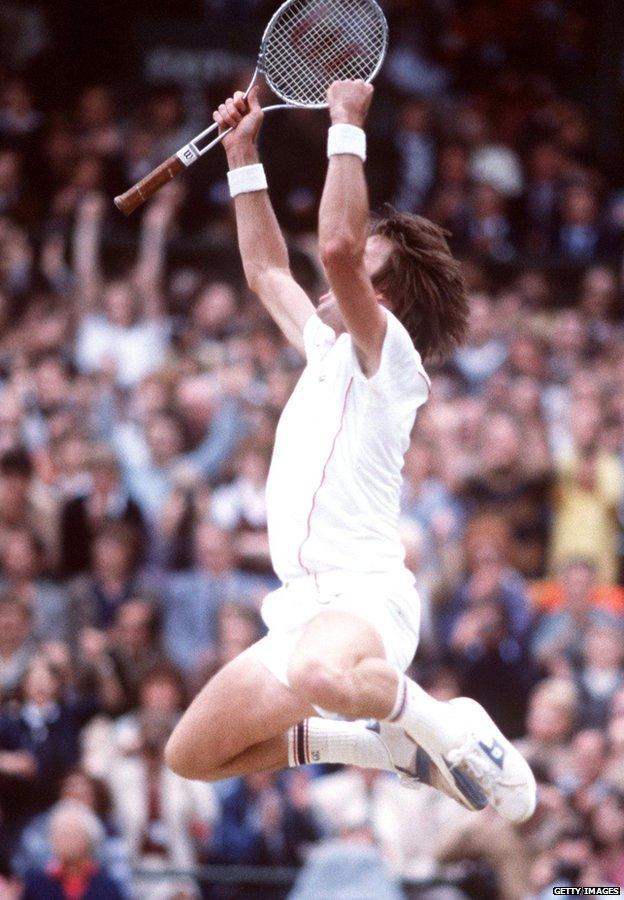

We did it! Jimmy Connors and his trusty steel Wilson T2000, winning Wimbledon in 1982

When Jimmy Connors blasted his way to victory at Wimbledon in 1974 the metal racquet had truly arrived. (Billie Jean King had won the 1967 US Open using a metal racquet but later returned to wooden racquets.)

But Connors' allegiance to the new technology divided opinion among players and fans.

Some, as you'd perhaps expect, were worried about the direction the sport was going in - concerned it was drifting into a situation where it was a contest between racquets, not athletes.

Connors used a Wilson T2000 until the mid-1980s, by which point it was he himself being left behind in the technology stakes. His rivals had shifted to even more advanced technologies and manufacturing techniques.

The result of all this innovation? A sport that was on its way to changing beyond all recognition.

Well, that's what would have happened, had those in charge not decided to get a handle on things.

Unlike Slew Hester, those responsible for tennis regulations today - the International Tennis Federation (ITF) - are extremely bothered about technology. They keep tabs on everything - squishing every ball, for example, to test it makes the grade. In summary: bouncy, but not too bouncy.

Slew Hester: liberal views on tennis tech

At their headquarters in Roehampton, south-west London, you'll find a series of machines all designed to test out equipment - each a charmingly home-made contraption that has the air of a mad inventor about it. Whirring beasts, built using trial and error... and kept together, in places, by gaffer tape.

When the ITF looks at racquets its principal concern is that they may offer too much power.

Given a free rein, a manufacturer could make a racquet so good at smacking the life out of a ball that the game of tennis would quickly descend into being little more than a serving competition. In other words, crushingly boring.

In one corner of the ITF's workshop is the machine for testing racquet power.

The handle is taped to a big motor that whirrs round at a rate far quicker than the human eye can manage. After getting to full speed, a tennis ball plops from a chute above, timed just right to hit the racquet's sweet spot.

A satisfying thwack smashes the ball through a hole and onto a metal board. It's angled upwards to take the pace out of the ball which subsequently drops comparatively gently into a bucket. Magnificent engineering.

A computer, watching carefully, tells the testers how fast the ball was going - 120mph, in the test the BBC saw, falling nicely within the limits. For context's sake, Andy Murray's best ever effort is 145mph.

Evolving sport

New equipment must come here before it's allowed to be used on the tour circuit, or even sold in shops.

"There's nothing wrong with innovation," says Dr Stuart Miller, who heads up the science and technical department at the ITF.

"But we need to make sure that it's the players who are the primary determinants of outcome.

The process of quality control for elite tennis racquets is intense - this machine snaps them in half

"To do that we need to make sure that we tread a fairly fine line between allowing that innovation to take place so the sport can evolve, but also making sure that it's the players who determine who wins the match, and not the equipment."

Peppered around the ITF warehouse are the racquets that never made it. There's one with the strings that are tied around the outside of the frame, and others with comically large heads.

The decisions made here make a huge impact on the game. Getting it wrong, and allowing a racquet that gives an unfair advantage to players, would bring the game into disrepute.

Gram by gram

Sometimes it's restriction that breeds innovation and invention - giving engineers problems to solve and barriers to get around can often yield more creative results than an entirely blank canvas.

It was with this in mind that the BBC nipped to the Austrian town of Kennelbach, population 1,883. It's a small part of the world defined by the company that has set up shop here, Head.

Head has been at the forefront of developing tennis technology since the 1950s. For some time, all Head racquets were made here, but now their process is split in two - mass-market racquets (the sort you'd buy in High Street sport shops) are produced in China.

In Kennelbach it's the very top end. A massive fridge keeps materials in top condition, and each racquet is treated like a priceless artefact.

Advancements in technology mean amateurs can get the elite racquet treatment

Novak Djokovic's racquet is made here to his exact specification, so too the likes of Andy Murray, Tommy Haas and Maria Sharapova.

But also manufactured here is what's seen as the latest important development in tennis tech - and for once it's something that helps out amateur players, rather than the big guns.

Head's custom-made service gives amateur players the chance to have the same kind of attention to detail that the elites demand.

But, rather than having to travel to Kennelbach, various intricate data points can be selected using the company's website. The changes are precise - you can specify the racquet's weight, gram by gram.

The racquet's frame is still made in China - but the finishing customisation touches are applied in Austria. It gives players an edge, argues Ralf Schwenger, head of research at Head.

"Each player is different, each player has different strokes," he says.

"Custom-made really gives the player the option to have his individual, perfect racquet."

'Small difference'

In Formula One, a sport that is defined by its technology, the competition is as much about the car as it is about the driver.

Often, enthusiasts will talk of the best drivers not having a good year because of the quality of their car.

Determination and skill is the real differentiator, not your equipment, coaches insist

This would be a nightmare scenario for tennis. If a player with more money is able to shell out on a custom-made racquet, does that give him an unfair advantage?

"It might make a small difference," says Miles Maclagan, an elite tennis coach who counts Andy Murray and Laura Robson as among those he has coached.

"[But] you have to put in the hours, you have to have the skills, and you have to have that just pure determination to succeed."

No racquet can replace the power provided by heart and effort, he says.

Techy future

The most dramatic change in tennis racquet tech over the years was that initial transition from wood to steel.

And there are more material changes to come - with the leading tennis firms looking at how to make full use of graphene, the so-called super material. Graphene is stronger and lighter than anything else out there, as explained by Head in an intriguing clip using a bumble bee as a tennis racquet metaphor, external.

Head's Ralf Schwenger says the firm never wants to change the nature of the game

Less obvious changes to racquets include inbuilt tech. Sensors, monitoring how you play, can give the sort of detailed feedback no coach ever could.

As we approach the first Grand Slam of 2015 - the Australian Open - all of these technological changes are being wilfully embraced, as long as the spirit of tennis also remains.

"Of course, we want to provide each player [with] that racquet that enables him to be the best player he can be," Head's Ralf Schwenger says.

"On the other side, we don't want to have a change of the nature of the game."

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC, external