Game of drones: As prices plummet drones are taking off

- Published

Drones are being used in more and more industries - this is the Sky TV drone used for filming sports coverage

Londoner Charles Christie-Webb runs a small estate agency out of a double-decker bus in Camden Town.

A few months ago, for £750 ($1,130; €960) he purchased a DJI Phantom drone, which carried a Go-Pro camera he could pair with his iPhone.

With some assistance from his son, Mr Christie-Webb began filming from the air the 200-odd streets where he sells properties, describing their history and styles of architecture to prospective buyers.

He is one of a growing number. Between January and October 2014, the number of organisations permitted by the UK's Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) to fly drones under 20kg rose by 80%.

Drones are taking off.

Charles-Christie Webb, of Camden Bus Estate Agents, and his drone outside the London Bus that serves as his office

Hovering ahead

"The price has dropped so much in the past year," says Roger Sollenberger of Texas drone firm 3D Robotics.

"These things were enormous, complicated, and incredibly expensive to build three years ago," he says, "and now anyone can just buy one, for less than $1,000 (£660; €840)."

Andreas Raptopoulos, chief executive of drone firm Matternet in Silicon Valley, compares the sudden drop in price of drone technology to the rise of personal computing in the 1970s.

"We're at a time where there are big mainframes - commercial aircraft - but also Spectrums and Commodores which people can acquire at low cost and do many things with," he says.

"And in coming years you're going to see the Apple-1s."

Early business use of drone technology includes aerial photography for roof surveys, monitoring of crops, forest management, or particularly heavenly wedding photographs.

Now, not only are off-the-wall models becoming cheaper, but they are being joined by an increasing number of specialised devices.

For example, in construction, US-based Skycatch (which recently raised $13.2m of venture capital funding) is developing special drones adapted for logging, mining, and construction companies to track progress on sites.

Growing Skynet

Many of the tech sector's best and brightest have been lured to the yard to play with drones.

Jay Bregman left his job as chief executive of Hailo in October 2014 to begin a drone start-up.

Wired editor Chris Anderson left the magazine in 2012 to found drone start-up 3D Robotics, or, as the magazine put it, "to spend more time with his robots", external. He is also the man behind online forum DIYDrones.com.

This is 3D Robotics' latest drone, the X8+

DIYdrones.com, the forum created by former Wired editor Chris Anderson, with 50,000 members

The giants are involved as well.

Both Google and Facebook are developing low-flying, solar-powered drones able to fly nonstop to provide internet signal to places in the world where it is non-existent.

Google last year gobbled a drone start-up called Titan Aerospace as part of its Project Loon. Facebook has been co-operating in a project called Internet.org with Nokia, Ericsson, Samsung, Qualcomm, MediaTek and Opera.

In September, Facebook announced the project's flying wi-fi hot spots - solar-powered, and the size of Boeing 747 aeroplanes, just much lighter - could be in use by 2018.

Early drone rangers

Philippe Francken founded Bristol Drones last March.

"I must admit I was a bit bored at my old job," he says, "and basically I'm quite into technology."

He started looking at Kickstarter, a crowdfunding platform featuring many new technology start-ups, and was impressed by developments in drones, and their cost.

"It was a very minimal investment, under £500, so I couldn't go wrong - so I looked into building up a company, which turns out to be quite easy in the UK."

It was only later that he discovered the regulatory requirements for businesses using drones.

"If you do it commercially, you become an aircraft pilot basically, you have to follow a course, be a licensed operator, get the CAA involved, receive Permission for Aerial Work (PAW), get the right insurance in place, and get an operations manual," he says.

onsevernbeach-philippefrancken.jpg)

Philippe Francken takes a selfie using one of his company drones

Mr Francken says UK regulators are still getting up to speed with the technology, with the occasional result of confused guidelines for operators.

But he prefers the UK's approach, in which everyone has the right to fly - as a hobbyist, up to 400ft (120m), with a visual line of sight - to the US's where, he says, "everything is banned unless you have a special licence from the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration)."

His company so far has focused on doing roof surveys. "A lovely old lady had a problem with a neighbour who said something in her roof needed repairing," says Mr Francken.

"It took an hour of chatting with her, flying and processing, and I had proof her roof didn't need anything at all. She didn't need to have a builder come in or scaffolding go up.'

Roof surveys are easy to do using drones and have a high return, according to Bristol Drones

Medical flight

Though drones burst into the public consciousness during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Matternet's Andreas Raptopoulos is keen to emphasise their lifesaving uses.

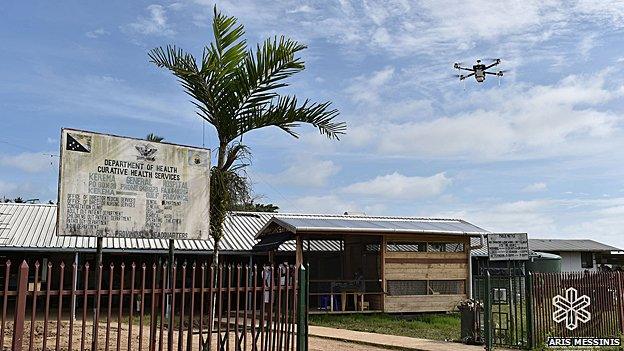

His company conducted field trials last year with Medecins Sans Frontieres in Papua New Guinea, testing drones' ability to ferry samples and medicines back and forth in a country where 6,000-10,000 people have a highly drug-resistant strain of tuberculosis, and roads are poor.

Matternet's next-generation drones are designed to fly independently, effectively "a computer that flies".

"You select a place on the map you want it to go, and it executes that flight in a completely autonomous fashion," says Mr Raptopoulos. Its software - much of it on the cloud, some on the vehicle - calculates the optimum path.

He predicts that once regulatory issues are resolved, drones will revolutionise small-package delivery, where the so-called last-mile of the delivery cycle accounts for 70% of the cost.

Matternet began life as a 2011 student project in Silicon Valley's Singularity University, before Arturo Pelayo and several other members splintered off to form their own company, Aria, saying they wished to pursue a more open-source approach.

They are working on base stations armed with 3D printers intended to service drones from any manufacturer.

Matternet's quadcopter in medical field trials in Papua New Guinea. The company hopes to launch later this year

The quadcopter is designed for areas where roads are poor or non-existent

More fully automated drones also play highly in the plans of 3D Robotics, says Roger Sollenberger.

The company is North America's largest consumer and commercial drone manufacturer, with France's Parrot and China's DJI the other two big makers.

3D Robotics and Linux have collaborated on an open-source flight code, called Dronecode.

Mr Sollenberger says drone technology has lent itself to open-source development, on forums such as DIYdrones.com, which has 50,000 members.

"About 90% of the internet runs on open-source kernels, like the Apache HTTP servers," he says.

"We want to democratise the skies."

With a burgeoning sector spurring technology development, price points are continually plunging, luring more people like Mr Christie-Webb and Mr Francken to make business out of drones.

Regulators are slowly devising procedures to integrate drones into their airspace, though the FAA appears unlikely to meet Congress's September 2015 deadline to open all US airspace.

It has so far permitted only 13 companies to operate drones commercially, including an estate agent in Tucson, Arizona, external, and a Washington state firm making crop-monitoring drones. The operators must hold Private Pilot licences, and the drones must remain within line of sight.

But for business in general, the next step seems to be droning on.

- Published13 January 2015

- Published8 January 2015

- Published6 January 2015

- Published2 January 2015

- Published30 December 2014

- Published26 December 2014